Parihaka

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library of New Zealand Topics

Parihaka was invaded on 5 November 1881. These resources give some background to Te Rā o te Pāhua (the Day of Plunder), the prophets Te Whiti and Tohu and their non-violent passive resistance to the confiscation of whenua Māori. It also looks at how and why the place and it’s people are remembered today. SCIS no. 1892958

social_sciences, arts, english, history, health, technology, Māori

Parihaka Pa

Alexander Turnbull Library

Parihaka ploughing campaign begins

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

"Parihaka"

Puke Ariki

Parihaka teaching resource

Services to Schools

Erueti Te Whiti-o-Rongomai III - Sketch made by William Francis Robert Gordon

Alexander Turnbull Library

Actions at Parihaka

Services to Schools

Flag, Parihaka

Puke Ariki

Ngā Tātarakihi o Parihaka

Services to Schools

Invasion of pacifist settlement at Parihaka

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Former prisoners return to Parihaka

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Call for taonga to be returned to Parihaka from Nelson

Services to Schools

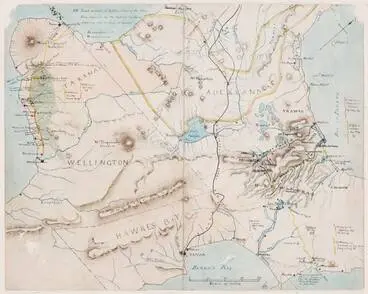

‘Alienation of Land within the Parihaka Block’

Waitangi Tribunal Unit

Te Whiti and Tohu – Parihaka

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

John Bryce. Native Minister

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Tātarakihi - The Children of Parihaka

NZ On Screen

Parihaka

NZ On Screen

Parihaka gatherings

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Parihaka

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

The New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

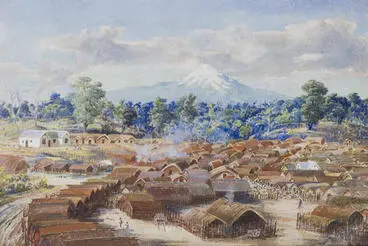

‘Comet over Mt Taranaki and Parihaka’

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Te Whiti-o-Rongomai III, Erueti

Services to Schools

Reconciliation package for Parihaka

Services to Schools

Why wasn’t I told?

Services to Schools

Truths far greater than myths

Services to Schools

Parihaka — Past, Present and Futurre

Services to Schools

Parihaka Pā

Services to Schools

Replace Guy Fawkes with Parihaka Day

Services to Schools

Parihaka Peace festival

Services to Schools

Studying Parihaka

Services to Schools

Making connections

Services to Schools

Historic caves have a story to tell

Services to Schools

Te Pire Haeata ki Parihaka/Parihaka Reconciliation Bill

Services to Schools

Apology to Parihaka

Services to Schools

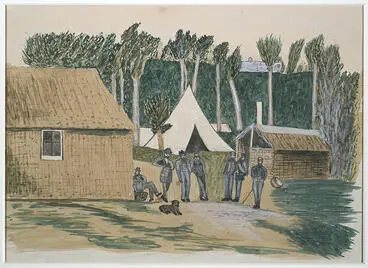

A photographic survey of 1881

Services to Schools

Auahi-roa and auahi-tūroa, means ‘long smoke trails’, 2 Māori names for comets. Te Whiti’s name was said to be derived from a comet. However he was in prison in 1882 when this photo was taken. Controversy surrounds this image. Many say that the image has been touched up with the addition of the comet and the snow-covered mountain. In her book The Parihaka Album, Rachel Buchanan concludes that this image shows the willingness of people to believe in the magical or providential powers of Te Whiti and Parihaka.

The comet in the sky

Services to Schools

This lengthy report is about Parihaka and the strained relationship between the followers of the 2 peace prophets. Tohu and Te Whiti, which the writer suspects was contrived to sustain the interest of the natives. The account laments the lapse of Parihaka over the years. However on 17 March 1911, there was a big gathering of natives along with James Carroll, then acting-Premier and Minister for Native Affairs along with other dignitaries, including Dr Pomare. This was to honour the departed prophets in accordance with Māori customs. The report goes on to cover the events of the day, where Māori etiquette overcame the uncomfortable situation between the Te Whiti and Tohu factions.

Respect to the departed prophets

Services to Schools

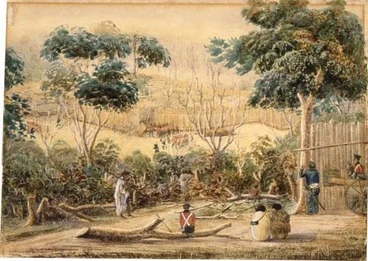

John Bryce, the man in uniform was Minister for Native Affairs and of Defence in 1881. The image symbolises the government's treatment of passive resisters at Parihaka by cutting off supplies of food (flour and sugar) to the Māori, hoping to starve them into submission. In the background are military tents and figures of native Māori ploughing fields. The ploughing campaign was a protest against European settlement on confiscated Māori land. It ended with the notorious sacking of Parihaka by armed constabulary in November 1881.

For diver’s reasons

Services to Schools

This report focuses on the attempt at reconciliation between the people of Parihaka and the Crown. The visiting Minister was presented with gifts by Tohu’s son. The report notes that some of the older natives stuck to their prejudices, while the younger men seemed eager to act on the advice to keep in with the laws of the Pakeha. Mention is made of increasing the land block for cultivation and residential needs. The visit from the minister was meant to replace discontent with a more ‘useful’ and productive occupation of the land.

Parihaka rejoicings

Services to Schools

This engraved portrait of Tohu Kākahi was created by John Ward for his publication ‘Wandering with the Māori Prophets Te Whiti and Tohu.’ Tohu was a teacher, prophet and a relative of Te Whiti. Inspired by Christian teachings he too decided that peaceful resistance was the only way to deal with the European confiscation of Māori land. On his arrest at Parihaka on 5 November 1881, he was charged with contriving to disturb the peace. He was released in 1883 and went on to rebuild Parihaka. He advised his people to stay out of debt and not drink. He died in February 1907.

Tohu Kākahi

Services to Schools

This is a brief report of the invasion of Parihaka and the arrest of Te Whiti, Tohu, Titokowaru and Hiroki. The Māori who were under instructions from Te Whiti not to resort to violence offered no resistance to Mr Bryce who arrived at Parihaka with an army of 1700 soldiers. Hiroki was handcuffed and later tried and hanged. People believed that the incident could have been avoided if the Māori were shown the land reserved for them in exchange for their confiscated land.

The Parihaka incident

Services to Schools

The Rangi Kapuia meeting house was built by Tohu Kākahi. The name means ‘Draw the people together; Gather the skies.’ It was opened in 1927 on Parihaka Pa. The playing card symbols seen on the building are similar to those used by Te Kooti. This house was built after the split between Te Whiti and Tohu. Both built new meeting houses. Te Whiti called his meeting house Te Raukura.

Rangi Kapuia

Services to Schools

Te Whiti o Rongomai was a powerful pacifist leader who preached the message of nonviolence from Parihaka. Elders of Parihaka believe he was born in 1815. He died on 18 November 1907. The words on his memorial read: “He was a man who did great deeds in suppressing evil so that peace may reign as a means of salvation to all people on earth …”

Te Whiti’s monument

Services to Schools

Taare Waitare, a wealthy Māori played an important role in Parihaka, especially in its management and modernisation. In this image, he is surrounded by children wearing white feathers in their hair to indicate they are followers of Te Whiti. The story goes that an albatross landed on Tohu’s marae at Parihaka and left behind a white feather. Others believe they saw a trail of light from a comet in the shape of a feather. The elders took this as a symbol of the Holy Spirit’s blessing over the peaceful movement. This is how the white feather (raukura) became a symbol of Parihaka’s passive resistance movement.

The white feather

Services to Schools

Confiscation

Services to Schools

GLORIOUS CAPTURE OE TE WHITI, TOHU, AND HIROKI. (Observer, 12 November 1881)

National Library of New Zealand

Te Tau O Te Pāhuatanga / The Pāhua

Services to Schools

Parihaka invaded by Dick Scott

Services to Schools

Fife and drum band at Parihaka Pa

Alexander Turnbull Library

Parihaka has waited a long time for this day

Services to Schools

The Parihaka prisoners and the legend of the caves

Services to Schools

The legacy of Parihaka

Services to Schools

Stories of place in Aotearoa NZ

Services to Schools

The pa, the president and the prophet

Services to Schools

Parihaka, 5 November 1881

Services to Schools

THE PARIHAKA "RIOTERS." (Marlborough Express, 29 November 1881)

Services to Schools

Te Whiti arrested

Services to Schools

The Parihaka meeting. (Timaru Herald, 03 November 1881)

Services to Schools

New insights into the 1881 invasion

Services to Schools

Anthony Ritchie: Remember Parihaka

Services to Schools

Colonists and courts

Services to Schools

The Wairau Affray 1843

DigitalNZ

The Story of Rua Kēnana, 1916

DigitalNZ

The Dog Tax Conflict 1898

DigitalNZ

The story of Te Kooti 1868-73

DigitalNZ

The Northern War 1845-46

DigitalNZ

War in the Waikato 1863-65

DigitalNZ

Parihaka name to be protected

Services to Schools

![Parihaka International Peace Festival 2009 [poster] Image: Parihaka International Peace Festival 2009 [poster]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fcollection.pukeariki.com%2Frecords%2Fimages%2Flarge%2F86435%2F913b5c0c1dd234886502597c5e978df1777abfec.jpg&resize=368%253E)