Māori creative writers

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library Services to Schools

This story provides links to resources about some of New Zealand's significant Māori creative writers.

INTRODUCTION

Māori literature was traditionally transmitted orally. Written literature began in the 19th century with missionary ethnographies and collections of Māori myth. Māori contributed to the ethnographies written by Pākehā such as George Grey and Elsdon Best. Their principal literary efforts were in the Māori newspapers, their own histories written in Māori and the literature associated with Māori millennial religions such as Pai Mārire, Ringatū, Iharaira and Rātana. These writings laid a foundation for later Māori readers and writers, of both non-fiction and fiction.

In the early 20th century Māori were still recovering from land and language loss, depopulation and the problem of education in a bilingual world. They were penalised for speaking Māori in schools, and mostly lived in rural areas until the 1940s. Māori had little opportunity or incentive to break through into the Pākehā world of higher education.

Source: Māori fiction – ngā tuhinga paki, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Te Ao Hou [No. 2 (Spring 1952)] - front cover

Alexander Turnbull Library

With few exceptions, a literate Māori middle class did not begin to emerge until after the Second World War. In the 1940s Te Rangi Hīroa (Peter Buck) and Apirana Ngata collected and wrote non-fiction (anthropology, songs and chants). By and large, fiction was not an abiding concern for Māori writers, and nor were there publishing outlets for Māori fiction, but this would soon change.

Urban migration and education were the paths that led to Māori fiction written in English.

After the Second World War, Māori moved from rural areas into cities in large numbers. Māori, most of whom lived in urban areas by the end of the 1950s, gradually began to gain consistent access to secondary and tertiary education. Their children were acculturated into expressing themselves in spoken and written English rather than te reo Māori. A growing number became readers of English literature – and eventually some became writers.

By the mid-1970s, when genuine Māori fiction had unmistakably made its mark, almost 80% of Māori lived in urban areas – a complete reversal of the pre-war situation.

Source: Māori fiction – ngā tuhinga paki, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Apirana Ngata and Peter Buck, Waiomatatini, 1923

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Huia Publishers was established in 1991 to promote Māori writers and writing in te reo Māori. In partnership with the Māori Literature Trust, an award for Māori writers (now called the Pikihuia Awards) was established in 1995. Huia has published anthologies of short stories from the best of the Pikihuia entrants.

Huia also publishes and promotes Pacific writers and supports the Te Papa Tupu mentoring programme, established by the Māori Literature Trust to foster new writing by emerging Māori writers.

Source: Māori fiction – ngā tuhinga paki - A new breed of writers, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Into the Boil Up [Book review]

Landfall

HONE TUWHARE (NGĀPUHI)

Hone Tuwhare has the distinction of being the first Māori poet published in English. A boilermaker by trade, and a former communist, Tuwhare drew inspiration from R. A. K. Mason. His own work, however, is more expansive. Warm, good-humoured and full of appetite, Tuwhare’s poems have a breadth of appeal perhaps second only to Baxter’s.

Source: Poetry - James K. Baxter and poets of the 1950s and 1960s, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

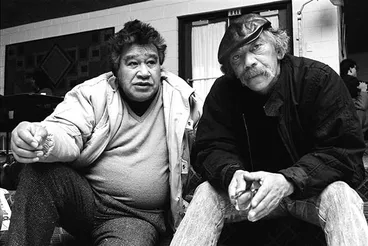

Hone Tuwhare and Ralph Hōtere, 1987

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Koha - Hone Tuwhare

NZ On Screen

Trentham military camp

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

PATRICIA GRACE (NGĀTI TOA, NGĀTI RAUKAWA, TE ĀTI AWA)

Patricia Grace (Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa, Te Āti Awa) is another key figure in Māori writing in English. By 2013 she had published seven novels, a number of story collections and several children’s books and received critical and popular acclaim.

Waiariki (1975) was the first story collection by a Māori woman writer. Potiki (1986) won the New Zealand Book Award for fiction. The importance of Grace’s work to Māori and to readers around the world has been recognised with the 2008 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

Source: Fiction - Māori and Pacific writers and writing about Māori, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Patricia Grace

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

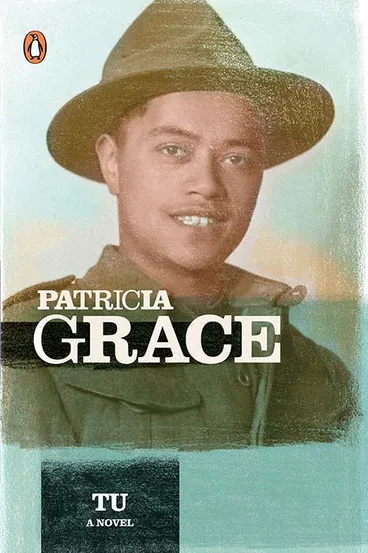

Patricia Grace's Tu

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Chapter and Verse: Patricia Grace

Radio New Zealand

WITI IHIMAERA (TE AITANGA-A-MAHAKI, TUHOE, TE WHĀNAU-A-APANUI, NGĀTI KAHUNGHNU, NGĀTI TAMANUHIRI)

By 2013 Witi Ihimaera (Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki, Rongowhakaata) had published 15 novels and numerous collections of stories, and edited significant anthologies of Māori writing. In 1972 he published Pounamu, pounamu, the first book of short stories by a Māori writer. Ihimaera followed with two novels, Tangi (1973) and Whanau (1974).

In the 1980s, after 10 years in which Ihimaera abstained from writing, his fiction became overtly political and more diverse. The matriarch (1986) traverses five generations of Māori history under colonisation; The whale rider (1987), about a young girl’s kinship with her ancestors, won international acclaim; Bulibasha (1994) is a Māori western which subverts western stereotypes; Nights in the gardens of Spain (1995) is a novel about coming out as gay.

Source: Fiction - Māori and Pacific writers and writing about Māori, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

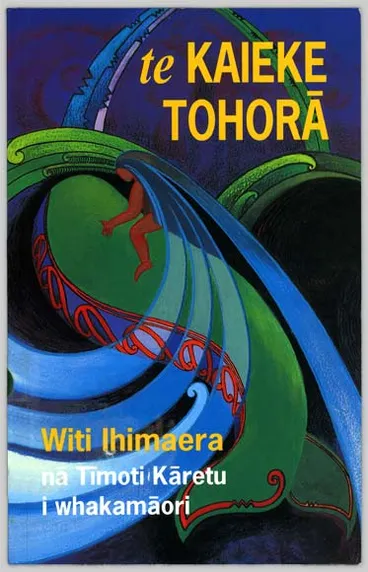

Te kaieke tohorā

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Witi Ihimaera

NZ On Screen

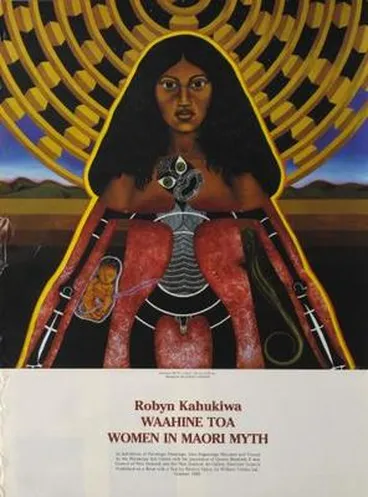

ROBYN KAHUKIWA (NGĀTI POROU, TE AITANGA-A-HAUITI, NGĀTI HAU, NGĀTI KONOHI, WHĀNAU-A-RAUTAUPARE)

Natural hair, 1986

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Robyn Kahukiwa: Waahine Toa: Women in Maori Myth

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

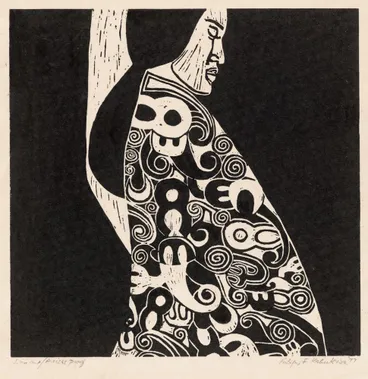

Untitled (Te Po)

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

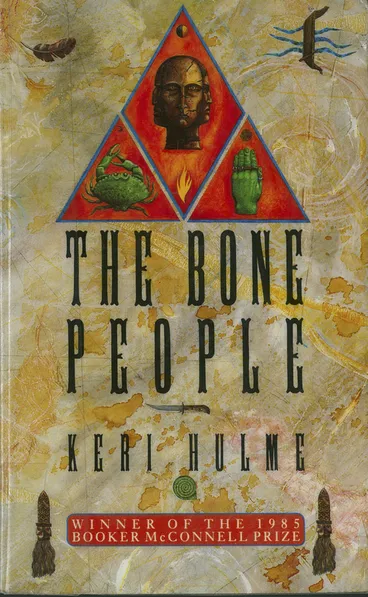

KERI HULME (KAI TAHU, KĀTI MĀMOE)

Keri Hulme (of Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Māmoe) has written in a wide variety of genres, including poetry, short fiction and non-fiction. Her poetic gifts are manifest in the language of her only novel, the bone people (1983), which was published by the Spiral Collective after difficulties with mainstream publishers, who wanted to heavily edit the book. Hulme’s reclamation of Ngāi Tahu identity and female power are clearly evident in the creation of the novel’s protagonist, Kerewin Holmes, a bookish recluse who lives on the wild margins of the coastal south.

The book is a heady brew of violence, dysfunctional relationships and a search for belonging. Its triumph at the 1985 Booker Prize has remained a seminal moment for both Māori and New Zealand fiction.

Source: Māori fiction – ngā tuhinga paki - Confronting reality, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

The Bone People

University of Otago

Kai Pūrākau - The Storyteller

NZ On Screen

ALAN DUFF (NGĀTI RANGITIHI, NGĀTI TŪWHARETOA)

Alan Duff’s first novel, Once were warriors (1990), describes the impoverished and violent lives of Māori gang members and their families. It is a searing indictment of violence and the conditions in which it thrives. The novel was made into a widely acclaimed film and has never been out of print. Duff published a number of novels subsequently, including two which continued the narrative of the Heke family from Once were warriors, but none received the acclaim of his first book.

Source: Fiction - Māori and Pacific writers and writing about Māori, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Once were warriors

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Author Alan Duff

Radio New Zealand

Duffy performance

Christchurch City Libraries

JACQUELINE STURM (TE WHAKATŌHEA, TARANAKI, TE PAKAKOHI, NGĀTI RUANUI)

The mother of Māori fiction, the talented J. C. (Jacquie) Sturm (of Te Whakatōhea and Taranaki) was the first university-educated Māori writer to appear in Te Ao Hou. She belongs to the exploratory phase of Māori fiction, when Māori began to negotiate the perils of publishing in the Pākehā-dominated media. Her 1955 story ‘For all the saints’ was the first fictional story in English by a Māori writer in Te Ao Hou.

Sturm experimented against the odds, finding a voice in the delivery of short fiction. She had a good selection of stories ready for publication by the mid-1960s, but lack of a publisher and personal circumstances meant she had to wait until 1983 before her first collection, The house of the talking cat, was published by the feminist Spiral Collective.

Source: Māori fiction – ngā tuhinga paki - Development of Māori fiction, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

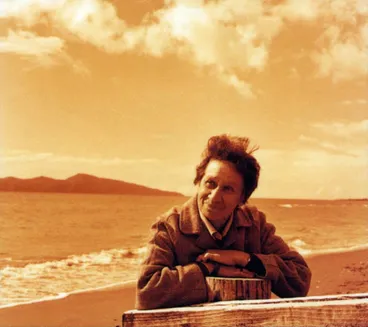

Jacqueline Sturm, 1990s

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

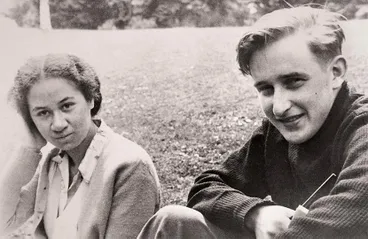

Jacqueline Sturm and James K. Baxter, 1948

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

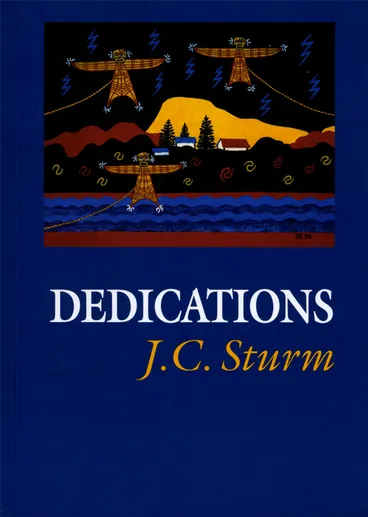

Dedications, by J.C. Sturm

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

KĀTERINA MATAIRA (NGĀTI POROU)

Kāterina Mataira pioneered the Te Ataarangi Māori language movement with Ngoingoi Pēwhairangi. Mataira has been described as the mother of kura kaupapa Māori (Māori-language immersion schools), and has also published books in Māori for children.

Source: Te mana o te wāhine – Māori women - Politics, business and language, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Te Ataarangi founder Kāterina Te Heikōkō Mataira

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Te Ahi Kaa for 02 (Here-turi-koka) 2009

Radio New Zealand

HONE KOUKA (NGĀTI POROU, NGĀTI RAUKAWA, NGĀTI KAHUNGUNU)

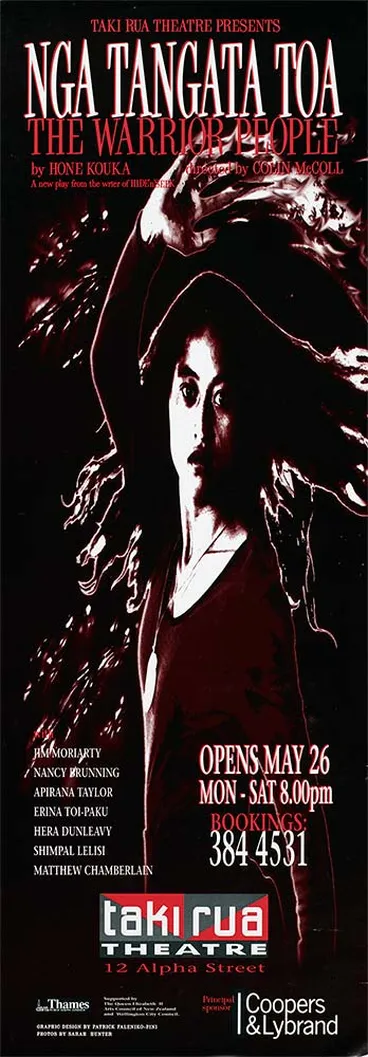

Hone Kouka, whose theatre career began at Taki Rua’s predecessor The Depot, later founded the Wellington independent company Tawata with playwright Miria George. Tawata has held a Matariki Festival annually since 2010, incorporating theatrical voices from Māori and ethnicities. In 2009 Kouka was made a member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for his services to Māori theatre.

Source: Māori theatre - te whare tapere hōu - Consolidating Māori theatre, 1990s onwards, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Hone Kouka, 2014

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Taki Rua productions: Nga tangata toa

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

TINA MAKERETI (NGĀTI TŪWHARETOA, TE ĀTI AWA, NGĀTI RANGATAHI)

Tina Makereti (Tūwharetoa, Te Āti Awa, Ngāti Maniapoto) has published short stories in literary journals, magazines and anthologies. Her collection of stories, Once upon a time in Aotearoa (2010), in which mythological beings and happenings are woven into stories of everyday life, won the inaugural fiction prize at the Ngā Kupu Ora Book Awards in 2011.

Source: Māori fiction – ngā tuhinga paki - A new breed of writers, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Tina Makereti

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

WHITI HEREAKA (NGĀTI TŪWHARETOA, TE ARAWA)

Whiti Hereaka, 2012

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

PAULA MORRIS (NGĀTI WAI, NGĀTI WHATUA)

Paula Morris (Ngātiwai) had a successful academic background and worked in the music and marketing industries overseas. She has an MA in Creative Writing from Victoria University of Wellington and in 2003 was appointed writer-in-residence at the prestigious University of Iowa Writing Program. Morris – in one literary generation – proved the point that access to education opens up opportunity for creative work by Māori writers and artists.

Her novels and short stories – Queen of beauty (2002), Forbidden cities (2008) and the award-winning Rangatira (2011) – have been fêted from the outset. Morris also edited the Penguin book of contemporary New Zealand short stories (2009). An internationalist and expatriate, she lived in England in 2013. Her work reflects the increasingly urbane and mobile experience of many Māori who settle overseas.

Source: Māori fiction – ngā tuhinga paki - A new breed of writers, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Paula Morris

Radio New Zealand

River of Truths [Book review]

Landfall

PETER GOSSAGE (NGĀTI MANUHIRI, NGĀTI WAI)

Peter Gossage retold myths and legends, and his bold, concise, colourful full-page illustrations had wide appeal. Patricia Grace collaborated with artist Robyn Kahukiwa on The kuia and the spider (1981) and Watercress tuna and the children of Champion Street (1984).

Source: Children’s and young adult literature - Fantasy and social realism, 1970s–2000s, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

ĀPIRANA TAYLOR (NGATI POROU, TE WHĀNAU-Ā-APANUI, NGĀTI RUANUI)

Celebrations in the capital

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Chapter and Verse: Apirana Taylor

Radio New Zealand

Drum Rhythms [Book review]

Landfall

This story was curated and compiled by Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, November 2020.

![Te Ao Hou [No. 2 (Spring 1952)] - front cover Image: Te Ao Hou [No. 2 (Spring 1952)] - front cover](https://images.digitalnz.org/ZUwwCgEBKSiev2ygmW7J3tEUyp8=/368x0/http%3A%2F%2Fteaohou.natlib.govt.nz%2Fjournals%2Fteaohou%2Fimages%2FMao02TeA%2FMao02TeAFCo%28h800%29.jpg)

![Into the Boil Up [Book review] Image: Into the Boil Up [Book review]](https://images.digitalnz.org/mIe_IC5zT7HzJZhgBjmchabajYs=/368x0/https%3A%2F%2Fi0.wp.com%2Fwww.landfallreview.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F04%2Fhuia_short_stories_11-225x300.jpg%3Fresize%3D225%2C300)

![A Professional Spectacle [Book review] Image: A Professional Spectacle [Book review]](https://images.digitalnz.org/0AO0pSHsnqDG1dvzyGLoKFG3cR8=/368x0/https%3A%2F%2Fi0.wp.com%2Flandfallreview.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F04%2Fmakereti_the_imaginary_lives.jpg%3Fresize%3D198%2C300%26ssl%3D1)

![Scribble, Scribble, Scribble [Book review] Image: Scribble, Scribble, Scribble [Book review]](https://images.digitalnz.org/d-CJCrhWd9Ry9xbhgRclahgTZ_U=/368x0/https%3A%2F%2Fi0.wp.com%2Fwww.landfallreview.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F07%2FImage.ashx_-197x300.jpeg%3Fresize%3D210%2C320)

![River of Truths [Book review] Image: River of Truths [Book review]](https://images.digitalnz.org/602PWUw16WG03zc590s6PDfUTKw=/368x0/https%3A%2F%2Fi0.wp.com%2Flandfallreview.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2018%2F07%2Ffalse_river_morris.jpg%3Fresize%3D172%2C300%26ssl%3D1)

![Drum Rhythms [Book review] Image: Drum Rhythms [Book review]](https://images.digitalnz.org/-_NhOAJX-KLopn2GqLkKvntqvLg=/368x0/https%3A%2F%2Fi0.wp.com%2Fwww.landfallreview.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2011%2F06%2F9781877257797-crop-325x325-206x300.jpg%3Fresize%3D219%2C320)