Kiingitanga

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library Services to Schools

Established in 1858, the King Movement, also known as Kiingitanga, aimed to create a unified voice for Māori in the face of colonisation and in particular, land loss. The movement continues to this day. SCIS no. 5380134

I muri, kia mau ki te whakapono,

kia mau ki te aroha, ki te ture.

Hei aha te aha, hei aha te aha.

After I am gone, hold fast to faith; hold fast to love; hold fast to law. Nothing else matters now – nothing.

Quoted in Carmen Kirkwood, Tāwhiao: king or prophet. Huntly: MAI Systems, 2000, p. 42

Source: Te Wherowhero, Pōtatau, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Revered artist Emily Karaka explores historic and contemporary land loss and it's impact in this painting from 2020.

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

INTRODUCTION

One of New Zealand’s most enduring political institutions, the Kīngitanga (Māori King movement) was founded in 1858 with the aim of uniting Māori under a single sovereign. Waikato is the seat of the Kīngitanga, and the early years of King Tāwhiao’s reign were dominated by the Waikato war of the 1860s.

The longest-serving Māori monarch was the beloved Queen Dame Te Atairangikaahu, who reigned for 40 years until her death in 2006.

Source: Kīngitanga – the Māori King movement, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

CONTENTS

- Te Tiriti o Waitangi | The Treaty of Waitangi

- The rise of Kiingitanga

- The 'Kingmaker'

- Ngāti Maniapoto

- The first Māori King - Pōtatau Te Wherowhero

- The second Māori King - Tāwhiao

- The 'King Country' is born

- Te Rohe Pōtae

- Te Hokioi, 1863

- Pai Mārire, 1864

- The Main Trunk Line, 1882

- Te Peeke o Aotearoa, 1886

- Te Kauhanganui, 1892

- Te Paki o Matariki, 1892

- The order of succession

- Te Puea Hērangi

- Ngāruawāhia & Tūrangawaewae marae

- Kiingitanga in the 21st Century

This map from 1884 represents the Crown's view of land ownership in the central North Island at this time.

Auckland Libraries

TE TIRITI O WAITANGI | THE TREATY OF WAITANGI

In 1840 Māori leaders decided for or against signing the treaty on the basis of its Māori text and after weighing various considerations. They wanted regulated settlement and support in controlling settlers and land sales. Trade and a cash income from employment opportunities would bring benefits to Māori communities. The new relationship would also enable them to avoid the intertribal warfare that had escalated in previous decades.

Over the 1840s and 1850s European settlement expanded and tensions over land worsened. Many tribes responded by strengthening their traditional tribal rūnanga (councils). In Waikato, tribes of the Tainui federation formed an alliance, aiming for tribal unity and drawing in tribes from other regions. In 1858 the Tainui chief Te Wherowhero was appointed head of this alliance and renamed Pōtatau, becoming the first Māori King. The aim of the King movement (Kīngitanga) was to retain land by withholding it from sale. The movement believed that the Māori king and British queen could co-exist peacefully.

George Grey, recalled to a second governorship of New Zealand in 1861, saw the King movement as a direct challenge to Crown authority and the future of British settlement. The government responded to the movement by invading Waikato with British troops. This action escalated into warfare that spread to Bay of Plenty and elsewhere. The conflict was officially described as a suppression of Māori who were in rebellion against the government, but some politicians admitted that it was a war to assert British supremacy.

These military actions demonstrated to many Māori that the government had not upheld their rights under the treaty. The subsequent confiscation of Māori land in Waikato, Taranaki, the Bay of Plenty and Hawke’s Bay left a further legacy of bitterness.

Source: Treaty of Waitangi - Dishonouring the treaty – 1860 to 1880, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

The War in Waikato in the 1860s was seen by some as evidence that the government had not upheld Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

THE RISE OF KIINGITANGA

There was no single Māori sovereign when Europeans first came to New Zealand. Instead, Māori tribes functioned independently under the leadership of their own chiefs. However, by the 1850s Māori were faced with increasing numbers of British settlers, political marginalisation and growing demand from the Crown to purchase their lands. Māori were divided between those who were prepared to sell and those who were not.

Some Māori attributed the power of the British to their one sovereign. This idea was particularly common among men who had travelled to England and had seen British institutions, industry and law and order in operation, such as Piri Kawau (Te Āti Awa), who met Queen Victoria in 1843, and Tāmihana Te Rauparaha (Ngāti Toa), who met her in 1852. They believed that a pan-tribal movement, unifying the Māori people under one sovereign equal to the Queen of England, could bring an end to intertribal conflict, keep Māori land in Māori hands and provide a separate governing body for Māori.

In 1853 Mātene Te Whiwhi and Tāmihana Te Rauparaha began travelling round the North Island looking for a chief who would agree to become king. However, most chiefs declined.

Source: Kīngitanga – the Māori King movement, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Te Rauparaha

Alexander Turnbull Library

Te Rauparaha’s moko

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Henare Matene Te Whiwhi

Alexander Turnbull Library

WIREMU TAMIHANA TARAPIPIPI TE WAHAROA — THE 'KINGMAKER'

Tarapīpipi was the second son of Te Waharoa of Ngāti Hauā. His mother was Rangi Te Wiwini. He was born in the early nineteenth century, possibly about 1805, at Tamahere, on the Horotiu plains.

During the late 1850s Tāmihana became involved in the establishment of a Māori king. For this he was given the title 'Kingmaker' by Pākehā.

A number of incidents, including a rebuff when he sought government support for his system of government for Ngāti Hauā, culminated in tribal meetings to consider resistance to further land sales and Pākehā encroachment, the potential disintegration of Māori society, and the need for political solidarity among Waikato, Ngāti Maniapoto and adjacent tribes.

At an important meeting held at Pūkawa, Lake Taupo, in 1856, Iwikau Te Heuheu Tūkino III of Ngāti Tūwharetoa supported Pōtatau Te Wherowhero of Ngāti Mahuta as king. Te Wherowhero was reluctant to take the position. Tāmihana had already decided that Te Wherowhero was the appropriate person.

On 12 February 1857 he wrote a letter to the chiefs of Waikato expressing the support of Ngāti Hauā, and suggesting a meeting of all Waikato and Ngāti Maniapoto tribes to ratify this.

In May 1857, at a meeting at Paetai, near Rangiriri, there was considerable debate on the merits of a Māori king and the question of support for the governor and Queen Victoria. Tāmihana spoke strongly to express his concern for the establishment and maintenance of law and order within the tribes. He hoped that a Māori kingship would provide effective order and laws, unlike the Pākehā government, which allowed Māori to kill each other and only involved itself when Pākehā were killed.

Source: Te Waharoa, Wiremu Tāmihana Tarapīpipi, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Dubbed the 'Kingmaker' by Pākehā, Wiremu Tamihana was instrumental in the appointment of the first Māori King.

Alexander Turnbull Library

NGĀTI MANIAPOTO

Ngāti Maniapoto is the main iwi (tribe) of the King Country. The iwi is named after the ancestor Maniapoto, a 17th-century descendant of Hoturoa.

Other tribes with affiliations to the region include Ngāti Mahuta of Tainui on the Kāwhia Harbour, Ngāti Raukawa in the north-east around Wharepūhunga, and Ngāti Tama in the south-west around Mōkau. Ngāti Hauā, a Waikato iwi, has interests south of the Pūniu River, near the region’s northern boundary, and the Whanganui and Ngāti Tūwharetoa people have interests around Taumarunui. The volcanic mountains in the south are of great cultural and spiritual importance to Ngāti Tūwharetoa.

Source: King Country region - Māori settlement and occupation, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Ngāti Maniapoto marae at Te Kuiti in the heart of the King Country.

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Ngāti Maniapoto were strong supporters of the Kīngitanga (King movement), a pan-tribal grouping based in Waikato territory. The Kīngitanga promoted Māori unity, authority and an end to land sales through the establishment of a Māori monarch.

Ngāti Maniapoto hapū met at Haurua, near Ōtorohanga, in 1857, where they endorsed the choice of Pōtatau Te Wherowhero of Waikato as king. This meeting was later called Te Puna o te Roimata – the wellspring of tears – referring to the troubled times that followed.

Source: King Country region - Māori and European contact, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

The original monument that marked the endorsement of Pōtatau Te Wherowhero of Waikato as the first Māori king.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

PŌTATAU TE WHEROWHERO — THE FIRST MĀORI KING, 1858-1860

In 1856 Iwikau Te Heuheu of Tūwharetoa convened a famous meeting known as Hīnana ki uta, Hīnana ki tai (search the land, search the sea) at Pūkawa, on the western shores of Lake Taupō. All the major tribes were represented. Here Te Heuheu proposed the famed Waikato chief Pōtatau Te Wherowhero for the kingship.

In 1841 Governor William Hobson had reported to London that Pōtatau was the most powerful chief in New Zealand. Mātene Te Whiwhi of Ngāti Raukawa had canvassed the genealogical experts Te Hūkiki Te Ahukaramū and Te Whīoi of Ngāti Raukawa, who believed that Pōtatau was the most suitable candidate. He had extensive genealogical connections with many iwi and his kingship could be well supported by the fertile lands and resources of the then wealthy Waikato. The wealth of Pōtatau was important, as his people would host many gatherings.

Source: Kīngitanga – the Māori King movement - Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, 1858–1860, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

The words 'Nui Tireni' (New Zealand) adorn this flag along with 3 symbols representing the country's main islands.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Te Wherowhero never regarded the kingship as being in opposition to the sovereignty of Queen Victoria, and wanted to work co-operatively with the government. Some of his associates, however, sought to prevent or hinder government activities in areas which supported the King.

Te Wherowhero had been much consulted by governors George Grey and Thomas Gore Browne on matters concerning Māori. However, after his acceptance of the kingship he was increasingly estranged from the governor's confidence. As land disputes increased in number and severity Te Wherowhero was in many cases forced into a position of opposition to government policy.

Source: Te Wherowhero, Pōtatau, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

This painting by George Angas from 1847 features the sacred maunga Taupiri in the background.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

This sketch shows a view of Ngāruawāhia and the Waikato River from 1872.

University of Otago

THE SECOND MĀORI KING — TUKAROTO MATUAERA POTATAU TE WHEROWHERO TAWHIAO, 1860-1894

King Pōtatau was succeeded by his son, Tāwhiao, who was proclaimed king on 5 July 1860 at Ngāruawāhia. Wiremu Tāmihana Tarapīpīpī Te Waharoa anointed him in the whakawahinga ceremony, using the same bible that he had used for Pōtatau’s investiture.

The first years of Tāwhiao’s reign were dominated by war. Governor Thomas Gore Browne demanded Tāwhiao submit 'without reserve' to Queen Victoria. Gore Browne’s successor, Sir George Grey, was also not prepared to accept dual sovereigns in New Zealand.

THE 'KING COUNTRY' IS BORN

The Waikato war ensued, with major battles leading to an ultimate defeat for Waikato. Tāwhiao and his fellow ‘Kingites’ were forced to retreat across the Pūniu River into Te Nehenehenui (the great forest), to their neighbouring Ngāti Maniapoto relatives.

Tāwhiao and his followers were declared rebels and some 1.2 million acres (almost 500,000 hectares) of their fertile lands were confiscated.

Tāwhiao and Ngāti Maniapoto leaders established an aukati (boundary) along the confiscation line at the Pūniu River, forbidding European intrusion. The territory beyond the aukati subsequently became known as the King Country.

Source: Kīngitanga – the Māori King movement - Tāwhiao, 1860–1894, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

The 34 year reign of King Tāwhiao was turbulent but he achieved a great deal for Kiingitangi during this time.

Alexander Turnbull Library

... in 1881, after a number of years of negotiations with the government, Tāwhiao and his followers symbolically laid down their weapons before the resident magistrate at Alexandra (Pirongia) and returned to the Waikato.

Tāwhiao did not renounce his efforts to have Waikato’s confiscated lands returned. In 1884 he travelled to England with several companions to seek redress from Queen Victoria. Tāwhiao’s tattooed face caused heads to turn in London, but he and his Māori embassy were declined an audience with the queen. He was informed by the colonial secretary that confiscations were a domestic matter under the jurisdiction of the New Zealand government.

Source: Kīngitanga – the Māori King movement - Tāwhiao, 1860–1894, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

This map shows the aukati or boundary line of the King Country; land outside this area was confiscated in 1864.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

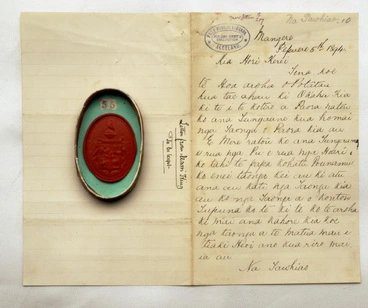

Befitting a king, Tāwhiao had his own seal, here used in communication with Govener George Grey in 1894.

Auckland Libraries

TE ROHE PŌTAE

Monuments in Ōtorohanga (top) and Taumarunui (bottom) commemorate the naming of Te Rohe Pōtae (the area of the hat) and the story behind it, in which King Tāwhiao (or, in some sources Wahanui Huatere) is said to have thrown a hat onto a map of the North Island.

Newspapers often mentioned that Tāwhiao wore a European-style hat. Some said it was white, and a photograph of him wearing a white top hat is held by the Alexander Turnbull Library.

Source: King Country region - Overview, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Te Rohe Pōtae monuments.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

This impressive studio portrait of Tāwhiao was taken between 1880 and 1894.

Alexander Turnbull Library

TE HOKIOI, 1863

The first [newspaper produced by Māori] was Te Hokioi o Niu Tireni e Rere atu na (January–May 1863). It was to be a voice for the Kīngitanga (Māori King movement) and Māori – and a far-reaching voice. As the first editorial noted, the advantage of the press was that it could carry their opinions to the peoples of the world.

Produced at Ngāruawāhia and edited by Wiremu Pātara Te Tuhi, the paper was printed on a press that had been donated by the Emperor of Austria to two Waikato chiefs visiting Vienna in 1859.

Source: Māori newspapers and magazines – ngā niupepa me ngā moheni - Māori-owned newspapers, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Wiremu Toetoe and Hēmara Te Rerehau learnt the skill of printing in Austria, and returned home with this printing press.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

PAI MĀRIRE, 1864

After the death of Te Ua [Haumene] in 1866, Pai Mārire continued as the faith of the Kīngitanga. Matutaera, the second Māori king, had been rebaptised by Te Ua in August 1864 as Tāwhiao (bind the world). Tāwhiao took these teachings back to the King Country. In 1875 he named his religion Tariao (the morning star), and from March 1885 he initiated the poukai, a three-yearly circuit of royal tours of the Kīngitanga derived from Deuteronomy 14: 28–29.

Source: Māori prophetic movements – ngā poropiti - Te Ua Haumēne – Pai Mārire and Hauhau, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Kiingitanga and Pai Mārire flags together represent the adoption of the faith by the King movement in the 1860s.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

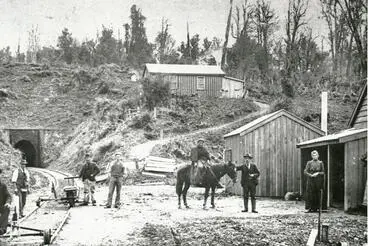

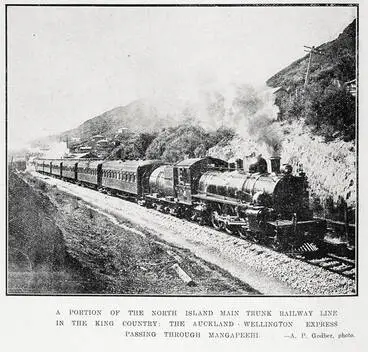

THE MAIN TRUNK LINE, 1882

In 1882 Ngāti Maniapoto agreed to a survey along the proposed route of the main trunk railway line through Te Rohe Pōtae. In return they wanted the government to agree to various proposals. Some of these were made in an 1883 petition by Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa and Whanganui tribes, who banded together to protect their interests in the western hill country.

Source: King Country region - Te Rohe Pōtae, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Main Trunk Line

Te Awamutu Museum

Development of railway lines through the King Country

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

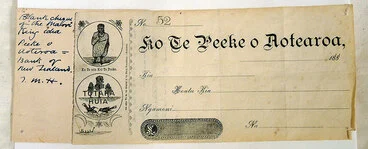

TE PEEKE O AOTEAROA, 1886

King Tawhiao established Te Peeke o Aotearoa in 1886; he was probably its organiser and manager. The bank operated from 1886 until about 1905. This is the one of the very few surviving bank notes.

Source: Banking and finance - Banking and finance to 1984, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Kiingitanga established its own bank and using their printing press printed their own currency.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

TE KAUHANGANUI, 1892

Tāwhiao continued his quest for mana motuhake (Māori political independence), setting up the Kauhanganui, a parliament, in 1892. It had a council of 12 tribal representatives (the Tekau-mā-rua), as well as ministers. Tupu Taingākawa, the second son of Wiremu Tāmihana (and kingmaker at the time), was the tumuaki (premier).

Source: Kīngitanga – the Māori King movement - Tāwhiao, 1860–1894, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Te Kauhanganui, the Kiingitanga parliament, met here at Maungakawa.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

TE PAKI O MATARIKI, 1892

... the Kīngitanga’s second paper, Te Paki o Matariki, [was] first published in 1892. The ornate coat of arms as masthead and the English subtitle on some issues spoke to its viewpoint: ‘The Independent Royal Maori Power of Aotearoa’. It was a paper for the affairs of the movement but it also engaged with national matters of political importance to Māori. Issues were in Māori, or both Māori and English. Over time it became less of a newspaper and more of a circular for the King movement.

Source: Māori newspapers and magazines – ngā niupepa me ngā moheni - Māori-owned newspapers, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

The design of this page references the Kiingitanga coat of arms as well as a waiata associated with the movement.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

THE ORDER OF SUCCESSION

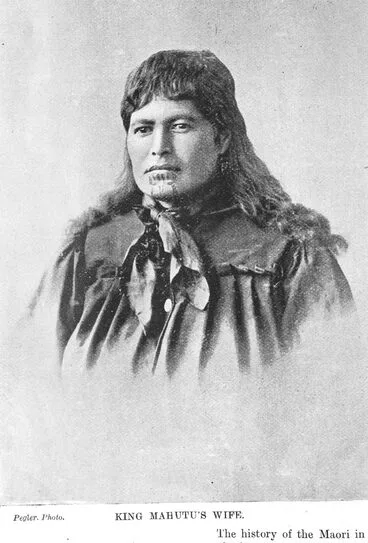

MAHUTA TĀWHIAO PŌTATAU TE WHEROWHERO, 1894-1912 (THE THIRD MĀORI KING)

Mahuta grew up during the wars of the 1860s and the period of isolation that followed. As a result, although trained in Waikato tradition and whakapapa, and in the composition of waiata, he received little if any European education. He spoke almost no English, and his handwriting remained shaky and unformed throughout his life.

Probably in the 1870s, Mahuta married Te Marae, a woman of strong, independent character who became a King movement leader in her own right. Mahuta and Te Marae had five surviving sons: Te Rata (eventually the fourth King), Taipū, Tūmate, Tonga and Te Rauangaanga.

... when Mahuta succeeded to the throne, many of the plans of Te Kauhanganui were being formalised for the first time and mana motuhake (local autonomy) was being realised to some extent. Soon after Mahuta's succession, Taingākawa, as leader of the King's government, announced the setting up of the kingdom's own courts for land, civil and criminal cases. Judges, registrars, police and clerks were appointed; dog taxes and fines for non-payment were organised. A minister of lands was appointed, to whom the kingdom's subjects could apply if they wished to lease out their lands. Land court block hearings were 'gazetted' in Te Paki o Matariki, the King movement's newspaper. Spokesmen were appointed to mediate tribal disputes. There was also a plan to set up King movement schools.

Source: Mahuta Tāwhiao Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

King Mahuta

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Kīngitanga flags: Mahuta's flag

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Te Marae

Auckland Libraries

TE RATA MAHUTA PŌTATAU TE WHEROWHERO, 1912-1933 (THE FOURTH MĀORI KING)

Te Rata Mahuta was the fourth leader of the Māori King movement. He inherited many of the leadership qualities of his predecessors, with the added support of 50 years of widespread Māori recognition of the special status conferred by his role as king.

In 1913 Te Rata took up Tupu Taingākawa's plans to present the British Crown with yet another petition asking for the restoration of confiscated lands. His mother, Te Marae, sold family land to finance the expedition, and King movement members agreed to support the trip by contributing a shilling each. A hui was held at Waahi on 1 April 1914 at which several speakers, including Apirana Ngata, attempted to convince Te Rata and Taingākawa to cancel their expedition. But they departed on 11 April, with Mita Karaka and Hōri Tiro Pāora as secretaries and interpreters, arriving in London in late May.

Te Rata was adroit at evading confrontation damaging to his mana. The First World War had commenced while he was still in England, and on his return he was asked whether Māori should assist the British King by enlisting. He is reported to have diplomatically recommended that the matter be left to individual choice: with other King movement leaders he felt that the confiscation issue needed resolution before Waikato men could be encouraged to enlist. Also, the King movement had revived and adopted the Pai Mārire religion, whose adherents were opposed to military service.

Source: Te Rata Mahuta Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

KOROKĪ TE RATA MAHUTA PŌTATAU TE WHEROWHERO, 1933-1966 (THE FIFTH MĀORI KING)

Korokī's father, Te Rata, died on 1 October 1933. Korokī begged [his relation] Te Puea [Hērangi] not to make him take his father's place: he did not feel fit for the task, and the people were so poor they could not afford to support a king. He expressed similar doubts to Pei Te Hurinui Jones. But at the tangihanga for Te Rata it was agreed by all the visiting chiefs that the Kīngitanga should continue and that Korokī should be the successor.

It was decided by the kāhui ariki (royal family) that Korokī must remain aloof from politics, yet every political action had to be done in his name, and his agreement, or at least his presence, obtained as an endorsement of their activities. Especially in his early years as King, he found himself pulled this way and that by the different requirements of his elders.

Many of the controversies in Korokī's reign related to the constant battle to maintain the dignity of the Kīngitanga and obtain both Pākehā and Māori recognition of it. It was a see-saw process, his special status alternately recognised and rejected.

Korokī's status and financial support for his role as King were key elements in the negotiations in the 1930s and 1940s for compensation for the confiscation of Waikato lands in the 1860s.

After difficult negotiations, some at the last minute, a short visit [by Queen Elizabeth] took place on 30 December 1953. Korokī had wanted to present the Queen with a loyal address prepared by Pei Te Hurinui, but this was not permitted. However, a signed and sealed copy was later forwarded. In this document, for the first time, a Māori King swore allegiance to the British Crown.

Source: Korokī Te Rata Mahuta Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

King Koroki Te Rata Mahuta Tawhiao Potatau Te Wherowhero and others

Alexander Turnbull Library

Creator unknown : Photograph of King Koroki's carved house at Ngaruawahia

Alexander Turnbull Library

Opening ceremony for Turongo House at Turangawaewae Marae, Ngaruawahia

Alexander Turnbull Library

TE ATAIRANGIKAAHU KOROKĪ TE RATA MAHUTA TĀWHIAO PŌTATAU TE WHEROWHERO, 1966-2006 (THE FIRST MĀORI QUEEN)

Te Arikinui, Dame Te Atairangikaahu was the first woman chosen to lead the Kīngitanga (the Māori king movement). She served as Māori queen for over 40 years, the longest reign of any Māori monarch. Te Atairangikaahu came to enjoy a national profile, embodying Māori identity and symbolising Māori mana at a time when Māori were increasingly asserting their language, culture and rights under the Treaty of Waitangi.

The Waikato Raupatu Settlement in 1995 was a key event during Te Atairangikaahu’s reign. The Waikato-Maniapoto Maori Claims Settlement Act 1946 had established the Tainui Maori Trust Board to distribute Crown payments to the people whose lands had been confiscated in the 1860s. However, the 1946 settlement did not acknowledge that Waikato had been invaded, and the payments were not inflation-adjusted. Te Atairangikaahu supported the work of her brother, Robert Mahuta, the Tainui Maori Trust Board and Nga Marae Toopu to obtain more comprehensive redress, including the return of land.

Their efforts resulted in the first historical Treaty of Waitangi settlement relating to grievances about the loss of land.

Source: Te Atairangikaahu Korokī Te Rata Mahuta Tāwhiao Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Kīngitanga flags: the flag of Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

TE ARIKINUI TŪHEITIA PŌTATAU TE WHEROWHERO VII, 2006 - 2024 (THE SIXTH MĀORI KING & SEVENTH HEAD OF KIINGITANGA)

Te Arikinui Tūheitia Paki, the present Māori king, is shown seated on the throne at Tūrangawaewae on 21 August 2006, soon after his succession. The line of Māori sovereigns stretches back to 1858, and Tūheitia is the seventh monarch.

Source: Waikato region - Te Kīngitanga, 1880 onwards, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Kīngi Tūheitia on the day he became king in 2006.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Kīngi Tūheitia was reknown for his commitment to kotahitanga.

Tagata Pasifika

TE ARIKINUI NGĀ WAI HONO I TE PŌ PAKI, 2024 - PRESENT (THE 2ND MĀORI QUEEN & 8TH HEAD OF KĪNGITANGA)

Following the tikanga of the Kīngitanga movement, the new Māori monarch ascended to the throne on the last day of the tangihanga for Kingi Tūheitia Pōtatau te Wherowhero VII, 5 September 2024. She is Ngā Wai Hono i te Pō Paki, the second Māori Queen, who was named by her grandmother Te Arikinui Te Atarangikaahu. She is the youngest of the three children of King Tūheitia and was 27 year of age on the day she was annointed.

Nga wai hono i te po annointed as 8th Maori monarch

Radio New Zealand

New Maori Queen due to give first speech

Radio New Zealand

TE KIRIHAEHAE TE PUEA HĒRANGI

Te Puea Hērangi was born at Whatiwhatihoe, near Pirongia, on 9 November 1883. Her mother was Tiahuia, daughter of Tāwhiao Te Wherowhero of Ngāti Mahuta, the second Māori King, and his senior wife, Hera.

Te Puea was thus born into the kāhui ariki, the family of the first Māori King, Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, in the difficult years following the wars of the 1860s and the extensive confiscation of Tainui lands. She was to play a crucial role alongside three successive kings in re-establishing the Kīngitanga (King movement) as a central force among the Tainui people, and in achieving national recognition of its importance.

Te Puea's influence became more firmly established among Tainui people during the First World War, when she led their opposition to the government's conscription policy. She understood the sense of alienation that the military invasion, occupation and confiscation of land had imposed upon the people, and understood, too, that the Kīngitanga held the key to restoring their sense of purpose. But the government was impatient with what it saw as defiance and disloyalty, and compounded Tainui feelings of injustice by conscripting Māori only from the Waikato–Maniapoto district.

Te Puea was now determined to rebuild a centre for the Kīngitanga at Ngāruawāhia, its original home before the confiscation, in accordance with Tāwhiao's wishes. She was dissatisfied with the swampy conditions at Mangatāwhiri and wished to make a new start in the wake of the tragic influenza epidemic of late 1918, which had struck the settlement with devastating effect, leaving a quarter of the people dead. Te Puea gathered up 100 orphaned children from lower Waikato and placed them in the care of the remaining families. But she needed a better home for them. In 1920 Waikato leaders were able to buy 10 acres of confiscated land on the bank of the Waikato River opposite the township and by 1921 Te Puea was ready to begin moving the people from Mangatāwhiri to build a new marae, to be called Tūrangawaewae.

Source: Hērangi, Te Kirihaehae Te Puea, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Te Kirihaehae Te Puea Herangi

Alexander Turnbull Library

Princess Te Kirihaehae Te Puea Herangi

Alexander Turnbull Library

Women on porch with wreaths & coffin

Auckland Libraries

NGĀRUAWĀHIA & TŪRANGAWAEWAE MARAE

[Tūrangawaewae is the] principal marae of the Kīngitanga, at Ngāruawāhia. In 1919 a Kīngitanga parliament house was built in the town, and in 1921 Te Puea Hērangi, grand-daughter of King Tāwhiao, inspired Kīngitanga supporters to build Tūrangawaewae marae. This fulfilled a prophecy of Tāwhiao that one day his people would return to Ngāruawāhia. The main meeting house, Māhinaarangi, was opened in 1929, and another, Tūrongo, in 1938. The Māori king frequently hosts visiting dignitaries there, and the marae complex is occasionally open to members of the public.

Source: Waikato places – Ngāruawāhia, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Ngaruawahia (riverbank with whare)

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Queen Elizabeth at Tūrangawaewae

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Opening of Tūrongo House, Tūrangawaewae marae, Ngāruawāhia

Alexander Turnbull Library

This waka, Te Winika, was restored by carvers at the carving school at Tūrangawaewae in the 1930s.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

KIINGITANGA IN THE 21ST CENTURY

The land protests of the 1970s and the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975 created a political climate in which the Waikato Raupatu Claims Settlement Act 1995 could eventually be passed. Signed into law by Queen Elizabeth II in the presence of the Māori queen, Dame Te Atairangikaahu, the settlement included some land, $170 million in compensation, and a formal apology for the devastation caused by the war and confiscations.

In the 2000s the Kīngitanga includes traditional practices and a modern corporate structure. The poukai, an annual series of visits by the king to Kīngitanga marae in and beyond the Waikato region, dates back to the time of Tāwhiao. So does the Tariao faith, combining Pai Mārire karakia and Kīngitanga ritual, which is used in many ceremonies.

The annual Koroneihana (coronation) hui, another long-standing tradition, brings together tribes from around the country for several days of celebrations and sporting events at Tūrangawaewae.

Source: Waikato region - Te Kīngitanga, 1880 onwards, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Kīngitanga poukai visits, 2010

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Nelson Mandela at Tūrangawaewae marae

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Waka at the Tainui settlement celebrations, Turangawaewae, Waikato, New Zealand, 22 August 2008

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Artist Buk Nin’s dramatic representation of Ngāruawāhia, painted in 1989.

The Arts House Trust

This story was curated and compiled by Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, August 2021 and updated in September 2024.