The 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library Services to Schools

By November 1918 most of New Zealand was experiencing the worst of the influenza pandemic. This story explores how the virus came to New Zealand, its impact and the national response by the New Zealand government and its citizens.

1918 influenza epidemic, New Zealand disasters, epidemics, pandemics, influenza, flu pandemic

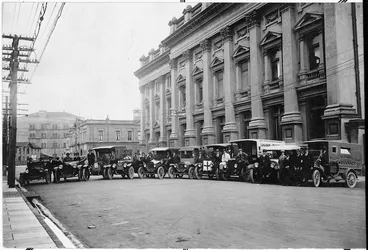

Automobiles and ambulances stand ready to play their role in the relief operations

Alexander Turnbull Library

BACKGROUND

When the ‘new pandemic flu’ first appeared in 1918 there was no immediate cause for alarm. The disease was no different from other strains experienced in the past – for example, it was unusually prevalent amongst young healthy adults. But most people affected by what would turn out to be ‘the first wave’ of the pandemic recovered.

Evidence suggests that this ‘mild’ first wave originated in North America. Influenza was present in many countries in late 1917 and early 1918.

The disease spread among recruits who entered Camp Funston in Kansas, then to camps in Georgia and South Carolina, and then rapidly across the Midwest.

American soldiers are also credited with bringing the disease to Europe, where the first cases appeared near the huge American transit camps at Brest and Bordeaux in early April. By June the first wave had spread across most civilian populations in Europe.

Source: The 1918 influenza pandemic - The pandemic begins abroad, NZHistory

QUICK FACTS

- The 1918 Spanish flu did not originate in Spain. It got its name when journalists first reported that the King of Spain, Alphonso XIII fell ill with a form of flu in May 1918.

- Historian Geoffrey Rice mentions in his book Black November, that there was an outbreak of a new kind of flu in Kansas in January 1918.

- In 1918 there were no drugs or vaccines available to treat the killer Spanish flu.

- People wore masks while schools, theatres and businesses shut down as preventive measures.

- There were two waves of the Spanish flu. The first wave was mild, and people recovered quickly. It was the second wave that was deadly enough to kill a person within days or sometimes hours of developing symptoms.

CONTENTS

This story on the 1918 flu pandemic in New Zealand covers the following:

- Did RMS Niagara bring the pandemic to New Zealand?

- Dr Robert Makgill did not agree

- Dr Makgill's theories of mutation

- The rally to save lives

- Some pandemic heroes

- Precautions and measures

- The huge toll

- Armistice Day without celebrations

- Impact on Māori communities

- In memoriam

- Glossary

- Supporting resources

DID RMS NIAGRA BRING THE PANDEMIC TO NEW ZEALAND?

RMS Niagara sails into Auckland with Prime Minister William Massey, his deputy Joseph Ward, and sick crew members

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Many people believed that the second wave of the 1918 influenza pandemic arrived in New Zealand in the form of ‘a deadly new virus’ on board the RMS Niagara. The ship arrived in Auckland with cases of influenza on board just a fortnight before the second wave took hold in the city. Speculation was further fuelled by rumours that the vessel had only been cleared because two of its prominent passengers, Prime Minister William Massey and his deputy Sir Joseph Ward, had refused to be quarantined. The official Health Department report on the pandemic, compiled by Dr Robert Makgill in 1919, provided evidence that suggests the Niagara carried nothing more than ‘ordinary influenza’.

Source: RMS Niagara - the 1918 influenza pandemic, NZHistory

QUICK FACTS

- RMS Niagara docked in Auckland in October 1918 when the first wave of flu had already begun in New Zealand.

- Twenty-nine crew members and several passengers from the Niagara had to be hospitalised in Auckland for influenza.

- There was a report that 6 people had already died of flu in Auckland days before the Niagara docked in Auckland.

- The increase in cases was two weeks later, which was outside the 48 hour incubation period when the Niagara docked in Auckland.

- There are many theories, but no one knows where the deadly strain originated, or how it got to New Zealand.

FLU " AT SEA. (Poverty Bay Herald, 18 November 1918)

National Library of New Zealand

THE NIAGARA (Evening Post, 06 November 1918)

National Library of New Zealand

FLU" ON SHIPS (NZ Truth, 30 November 1918)

National Library of New Zealand

DR ROBERT MAKGILL DID NOT AGREE

Dr Makgill provided evidence that Niagara not at fault

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

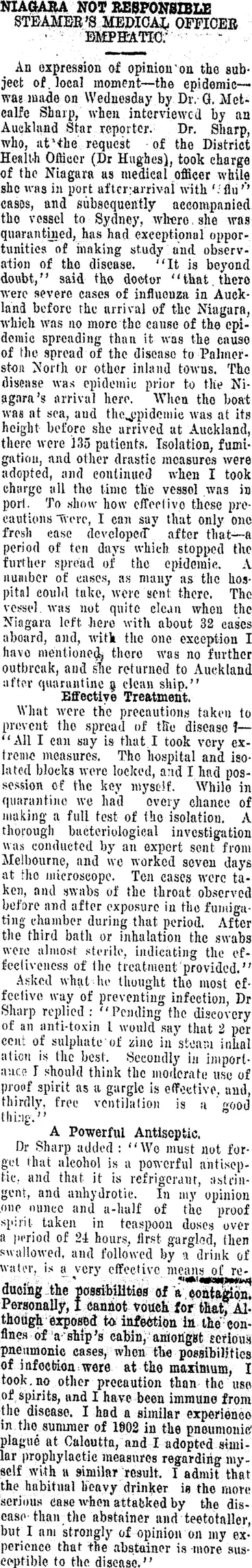

The official Health Department report on the pandemic, compiled by Dr Robert Makgill in 1919, provided evidence that suggests the Niagara carried nothing more than ‘ordinary influenza’. Makgill pointed out that the ship left North America well in advance of the second wave, making it ‘hard to see where it could have picked up a new "killer" virus’. He also noted that ‘all three doctors who examined the passengers and crew’ declared that the type of influenza onboard was ‘no more severe than the type that already existed in the city’.

He pointed out that if it had been carrying a deadly new virus, to which people had no immunity, ‘a rash of local epidemics’ should have appeared as people returned to their homes. They did not. Auckland's ‘explosive outburst’, and outbreaks of severe influenza in most other parts of the country, occurred ‘well outside of the 48 hour incubation period’.

Geoffrey Rice's research supports these observations. He determined that if the Niagara had been carrying a deadly new virus the peak of mortality for the whole country should have occurred on or about 7 November, not 23 November.

Source: The 1918 influenza pandemic - The pandemic hits New Zealand, NZHistory

QUICK FACTS

- People needed to be convinced that the Niagara was not solely responsible for bringing the second wave of flu to New Zealand.

- The government set up a commission with special powers to investigate the 1918 pandemic.

- Dr Robert Makgill wrote an official report on the pandemic for the Health Department in 1918.

NIAGARA NOT RESPONSIBLE (Tuapeka Times 4-12-1918)

National Library of New Zealand

DR MAKGILL'S THEORIES OF MUTATION

The first possibility arises out of Magkill's observation that the form of flu prevalent in New Zealand in September was itself changing in October. This suggests that the second wave may simply have been a deadly mutation of the first wave. The existing virus may have lain dormant for a time, appearing again in a more virulent form in October, perhaps triggered by the poor weather the country experienced that month.

The second possibility is that the second wave was a ‘deadly hybrid’ of the variant prevalent in New Zealand in September and another variant from overseas. The overseas variant may have arrived on the Niagara, but it might equally have been aboard any of the six other ships that arrived in Auckland in October. Either way, if the overseas variant presented as mild influenza until it recombined with the New Zealand variant, the authorities would have had no cause for quarantining any ship.

Source: The 1918 influenza pandemic - The pandemic hits New Zealand, NZHistory

QUICK FACTS

- Mutation means a change in an organism's genetic material or DNA.

- Some mutations can be useful, some have helped animals to evolve and adapt to their surroundings.

- Mutations can be harmful when viruses evolve or change. This can cause news strains of flu.

- People were more worried about infectious diseases like smallpox and tuberculosis at the time.

THE RALLY TO SAVE LIVES

Special powers conferred on District Health Officers under the Public Health Act

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

The directive from the Health Minister

There were consistencies in New Zealand's response to the influenza pandemic. Many of these arose out of a circular telegram the Health Minister, George Russell, issued to all borough councils and town boards. This ‘laid out a practical and comprehensive scheme of relief organisation in clear and concise language, and gave full initiative to the local authorities'.

Source: The 1918 influenza pandemic - Response to the influenza pandemic, NZHistory

Challenges for New Zealand Health Minister George Russell

The greatest challenge of Russell's ministerial career came late in 1918 when New Zealand was struck by the worst pandemic of modern times: the so-called Spanish influenza. Russell had to decide whether or not to quarantine the passenger liner Niagara when it arrived at Auckland on 12 October 1918. There had been a mild epidemic of influenza among the crew, with one death, but no passengers had been affected. Acting on the unanimous advice of the ship's doctors and port health authorities, Russell allowed the Niagara to dock without quarantine. This decision, it can now be shown, was medically correct but politically disastrous.

When senior health department officials went down with influenza, Russell took charge himself. Medical resources were at a low ebb because of the war, but Russell enlisted the help of the Defence Department to set up temporary hospitals and send army medical units to the worst-affected areas. He also advised local authorities how best to deal with the crisis.

Source: Russell, George Warren, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Volunteers doing Plunket washing during the 1918 influenza epidemic, Armagh Street, Christchurch

Alexander Turnbull Library

Volunteer medical and support staff outside Northcote Infants School - 1918 Influenza

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Doctors, nurses, health care workers and volunteers — they all played their part diligently and generously

Doctors, nurses, chemists, and voluntary organisations such as the Red Cross, St John Ambulance and district nursing associations all played crucial roles during the pandemic. But they were spread very thinly across the country, particularly in smaller towns, which meant relief efforts relied heavily on volunteers. Some women, free of employment when schools or shops closed, became lay nurses. Both men and women served on block committees, answering phones or checking on those reported to be ill. Still more people helped their families, friends and neighbours as best they could, particularly where there were young children that needed care. People with any sort of vehicle found themselves in particular demand: to take food or medicine to stricken families, to transport the sick or to take away the dead.

Source: The 1918 influenza pandemic - Response to the pandemic, NZHistory

Esther Tubman

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

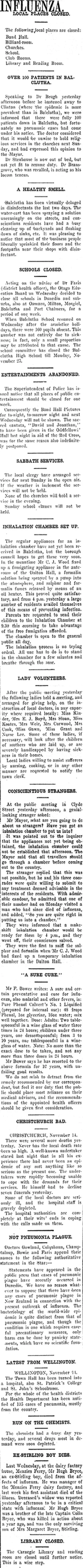

INFLUENZA. (Clutha Leader 15-11-1918)

National Library of New Zealand

SOME PANDEMIC HEROES

Dr Margaret Cruickshank

When the 1918 influenza pandemic struck she began working day and night, in many cases providing services well beyond those expected of a doctor. The son of her housekeeper recalled:

"Where the mother was laid low, she fed the baby, prepared a meal, and in many cases where whole families were laid low she would milk the family cow to obtain milk for their sustenance."

Margaret caught influenza herself and died of pneumonia at Waimate on 28 November 1918.

Source: Margaret Cruickshank, NZHistory

Dr Robert Makgill

During the First World War the number of staff working for the Department plummeted. Makgill himself served overseas for the first two years and, when he returned home in 1916, was seconded to the Department of Defence as assistant director of medical services (sanitation). He was eventually recalled to the Health Department in November 1918, replacing Dr Michael Watt (who had fallen ill with influenza) as deputy to the acting Chief Health Officer, Dr Joseph Frengley, and as district health officer in Wellington. In these positions Makgill played an important role in the latter part of the pandemic, taking the unpopular decision to close bars, breweries and wine and spirit merchants in Wellington, and then relieving Frengley in Auckland. Following the epidemic it fell to Makgill to front up for the Department; the Chief Health Officer, Dr Thomas Valintine, was overseas. Makgill prepared the Department's submission to the Epidemic Commission, which had been set up in early 1919 in response to public's demand for answers.

Source: Robert Makgill, NZHistory

Other names and organisations worth mentioning for their tireless work:

- The Boy Scouts were used as messengers and carried baskets of food to the ill.

- Dr Charles Little and his wife Hephzibah lost their lives fighting the pandemic in Christchurch.

- The Red Cross, St John's Ambulances and the Automobile Association worked day and night to treat and transport the sick.

- Nurse Esther Tubman, a New Zealand nurse who worked tirelessly with influenza affected in West Africa, before becoming infected herself. She died in Codford, Wiltshire.

QUICK FACTS

- 37 nurses and 14 New Zealand doctors lost their lives in the pandemic.

- Dr Makgill’s drafted the 1920 Health Act, laid the foundation for New Zealand’s public health system.

- Dr Margaret Cruikshank was the first woman doctor registered in New Zealand.

PRECAUTIONS AND MEASURES

People using the inhalation chamber in Christchurch

Christchurch City Libraries

Inhalation centres, closures and restricted hours

One action taken in many town and cities was to set up inhalation sprayers to disperse a solution of zinc sulphate to the public. Though ‘medically useless', this was the only approved preventative for influenza known to New Zealand's public health department. Most sprayers were set up in public buildings.

Another response in many towns and cities was to close or restrict opening hours for public facilities and businesses, and cancel or postpone public events and gatherings. In many cases these actions were initiated by those in charge of relief efforts. For example, as soon as influenza was declared an infectious disease – giving local authorities greater ability ‘to check or prevent the spread of disease' – Auckland's district health officer, Dr Joseph Frengley, ordered the closure of ‘all public halls, places of entertainment, billiard rooms and shooting galleries for at least a week'. In some cases individual businesses chose to close because of depleted staff numbers, or to free employees to nurse those in their households or to volunteer to assist relief efforts.

Source: The 1918 influenza pandemic - Response to the influenza pandemic, NZHistory

QUICK FACTS

- People were sprayed with zinc sulphate in 1918 to help prevent them from being infected.

- Spitting spread germs, as a result, it became unlawful to spit in public.

- Some people wore camphor balls to protect themselves against the flu virus in 1918.

- The Department of Health in 1918 dispensed little bottles of medicine with high alcohol content. These bottles of medicine became very popular probably because all liquor shops were closed as a precautionary measure.

- There was much debate about the usefulness of face-masks as a preventive measure against the spread of germs in 1918. This debate continues in the fight against COVID-19 in 2020.

Inhalator - 1918 Influenza

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Influenza instructions for nurses

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

THE HUGE TOLL

Children orphaned by the pandemic being looked after by Myers Kindergarten

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

It is clear that no matter how the second wave developed in New Zealand, it was many times more deadly than any previous influenza outbreaks. No other event has killed so many New Zealanders in so short a space of time. While the First World War claimed the lives of more than 18,000 New Zealand soldiers over a four-year period, the second wave of the 1918 influenza epidemic killed about 9000 people in less than two months.

Death did not occur evenly throughout the country. Some communities were decimated; others escaped largely unscathed

Source: The 1918 influenza pandemic - Uneven rates of death, NZHistory

Sound files

Listen to these sound files that relay vivid descriptions of the desperate times and experiences of the 1918 influenza pandemic in New Zealand.

Cures - the 1918 influenza pandemic

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

One family's story - the 1918 influenza pandemic

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Black plague - the 1918 influenza pandemic

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

ARMISTICE DAY WITHOUT CELEBRATIONS

Armistice Day and the spread of influenza

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

The only visible sign of celebration was the many flags hanging from the city’s buildings – and some of these were at half-mast in acknowledgment of the death of a former city councillor, Maurice Casey, from influenza.

Source: Armistice Day - Armistice Day and the flu, NZHistory

No community, organisation or government was left unscathed from the influenza pandemic. Even Prime Minister Massey was forced to adjourn the House of Parliament and close public galleries. At least 2 Members of Parliament died from the virus.

As it was the end of World War One, Armistice Day celebrations took a huge hit. District Health Boards banned all forms of gathering and official celebrations. However, many towns and cities went ahead with their Armistice celebrations, which is believed to have caused a spike in the number of infections around this time.

QUICK FACTS

- The 1918 flu pandemic was also called Black November in Aotearoa, New Zealand because of the number of people who died that month.

- The flu spread widely in October, peaked in November and was over by December.

- The flu spread very quickly as the government was slow in restricting travel throughout New Zealand.

- People collapsed within hours of contracting the flu and some died within 24 hours.

- There were no vaccinations and antibiotics to treat and protect people who fell ill with the virus.

Influenza at Featherston military camp

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Male and female death rates from influenza in 1918

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

IMPACT ON MĀORI COMMUNITIES

Nurses at Maori Hospital, Temuka, South Canterbury

Christchurch City Libraries

Historian Geoffrey Rice suggests that higher death rates among Māori (about eight times that of Pākehā) may have resulted from lower immunity, due to their isolation from colds and other minor respiratory ailments in the past, as Māori were then a largely rural population. He suggests that lower standards of housing, clothing and nourishment amongst Māori communities at the time also put them at greater risk.

Accounts of the devastation in Māori communities during these difficult times are hard to come by, particularly because Pākehā journalists did not often cover the plight of isolated rural Māori communities during the crisis. Below are a few rare examples.

Source: The 1918 influenza pandemic - Māori and the flu, 1918-19, NZHistory

QUICK FACTS

- Over 2,160 Māori died which was a significant proportion of their population then.

- Dr Māui Pōmare, was Minister for Native Affairs when he fell ill with influenza. He also had a relapse after getting back to work before he was completely well.

- Many Māori communities were neglected by the public health system, many turned to their traditional medicinal knowledge (Rongoā Māori) to deal with influenza.

- Dame Whina Cooper lost her father in the pandemic.

- Ngāti Maniapoto chief Hari Wahanui became infected when he attended a hui in Auckland to welcome his son and the Māori Battalion who had returned from the war. He died a few days later.

Māori influenza hospital

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

IN MEMORIAM

Callum Mahy, a monumental mason was sad to see so many unmarked graves of people who perished in the 1918 flu pandemic. Wanting to give something back to the community, he decided to build a memorial for the flu victims. With support from the trustees of Ngāti Te Whiti hapū he built a memorial at the New Plymouth cemetery.

The memorial was unveiled in November 1980 with a karakia and sprinkling of water as part of whakanoa, a rite to dispel tapu.

It is said that many of the graves were unmarked because of the sheer number of people who died in such a short time.

Monument built by Callum Mason for those who died in the 1918 flu pandemic

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Monument to flu victims

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Statue of Margaret Cruickshank, Waimate

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

GLOSSARY

Definitions below have been taken from theOxford Learner's Dictionary.

civilian- a person who is not a member of the armed forces or the police.

decimate- to kill large numbers of animals, plants or people in a particular area.

immunity - the body’s ability to avoid or not be affected by infection and disease.

incubation - the time between somebody catching a disease and the appearance of the first symptoms.

mortality - the number of deaths in a particular situation or period of time.

mutation - a process in which the genetic material of a person, a plant or an animal changes in structure when it is passed on to children, etc., causing different physical characteristics to develop; a change of this kind.

outbreaks - the sudden start of something unpleasant, especially violence or a disease.

pandemic - a disease that spreads over a whole country or the whole world.

pneumonia - a serious illness affecting one or both lungs that makes breathing difficult.

quarantined - a period of time when an animal or a person that has or may have a disease is kept away from others in order to prevent the disease from spreading.

strain - a particular type of plant or animal, or of a disease caused by bacteria, etc.

variant- a thing that is a slightly different form or type of something else.

virus- a living thing, too small to be seen without a microscope, that causes disease in people, animals and plants.

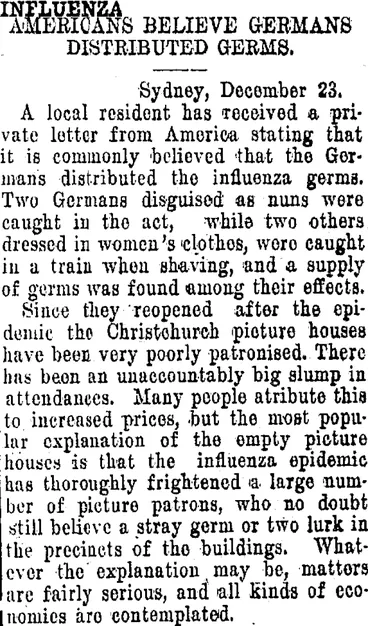

INFLUENZA. (Tuapeka Times 24-12-1918)

National Library of New Zealand

INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC (Otago Daily Times 25-11-1918)

National Library of New Zealand

SUPPORTING RESOURCES

Death by numbers — New Zealand Mortality Rates in the 1918 Influenza Pandemic.

Descriptive study of pandemic influenza amongst the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces, 1918 to 1919 — a study that used individualized data combined with historical documents to describe the course and impact of the pandemic amongst the entire NZEF.

Doctors and nurses lost to the Black Flu of 1918 — stories from Health Central of doctors and nurses who lost their lives during the pandemic.

Images and media — this media gallery has stories from people who lived through the 1918 pandemic in New Zealand.

Influenza — an article from New Zealand Geographic on the scale of death and disaster that New Zealand experienced during the flu of 1918.

1918 Influenza Pandemic— the Spanish flu was called different names in different countries but when it reached New Zealand it spread quickly decimating communities in the cities and in the countryside.

100 years ago, NZ was in the depths of a deadly pandemic. Are we ready for the next one? —are we ready for a virus that is very cunning, can jump into humans and transmit into a population that has no immunity?

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Memories from a Tragic Time in Taranaki — Jean Linklater's recalls life and some incredible stories of the pandemic in New Plymouth.

Pandemic: The Deadly Flu of 1918— the impact of the 1918 Flu pandemic in New Zealand how the government and communities tried to deal with it.

Story of the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic — Associate Professor Geoffrey Rice discusses with Kathryn Asare the Story of the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic and the death of over 8000 New Zealanders.

The 1918 influenza pandemic— the full story from where it began, how it reached New Zealand and the colossal loss of lives.

What we can learn about Covid 19 from past pandemics — 'tell the truth' is one of them. Lessons from the past from Professor John Barry.

The Māori experience of the Influenza Pandemic

The effects of the 1918 pandemic of influenza on the Māori population of New Zealand— the reasons why Māori suffered so many casualties.

EPIC— Find more information on this topic on EPIC. Databases recommended: Britannica School, World History (Gale in Context) and Science (Gale in Context). School login maybe required.

Kāhuipani— a journey of two children to the Tuakau bridge to find Te Puea who cared for over 100 orphans during the influenza epidemic in 1918.

1918 Influenza pandemic's devastating impact on Māori — a memorial plaque was placed at Pukeahu National War Memorial Park in memory of those who died in the flu pandemic of New Zealand.

New Zealand must learn lessons of 1918 pandemic and protect Māori from COVID-19 — vulnerability of indigenous people makes it imperative for them to be protected during a pandemic.

New Zealand troops and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

Military camps were dangerous places to be — the army camps at Narrow Neck in Auckland, Featherston and Trentham in Upper Hutt were the most virulent places to be avoided during the pandemic.

Mortality Risk Factors for Pandemic Influenza on New Zealand Troop Ship, 1918— the epidemiology and risk factors for death in an outbreak of pandemic influenza on a troop ship.

1918 Influenza pandemic— Featherston Camp suffered over 160 deaths in November 1918.

World War 1, influenza — an excerpt of an interview with army instructor, Charles Ritzema, who recalls the influenza epidemic at Trentham camp in 1918.

This story was curated and compiled by Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, April 2020.