Hauora: Taha Wairua - Spiritual Wellbeing

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library Services to Schools

The Taha Wairau component of Hauora refers to the spiritual (religious and non-religious) beliefs and values that determines the identify of a person or community and gives purpose to their lives.

BACKGROUND

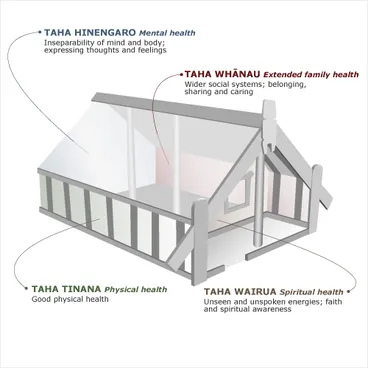

For our topic on Hauora: health and wellbeing. there are five dimensions.

An analogy for these dimensions commonly used (in Aotearoa New Zealand) is the Te Whare Tapa Whā Maori model of health. This references a whare (building) - its four walls and floor.

Each wall (and the foundation or floor) represents the following dimension of hauora: health and wellbeing which are:

- Taha hinengaro - mental and emotional wellbeing

- Taha whānau - social wellbeing

- Taha tinana - physical wellbeing

- Taha whenua – connection with the land, environmental wellbeing

- Taha wairua - spiritual wellbeing.

Taha wairua - spiritual wellbeing

This concept is defined as:

the values and beliefs that determine the way people live, the search for meaning and purpose in life, and personal identity and self-awareness (for some individuals and communities, spiritual well- being is linked to a particular religion; for others, it is not.

Source: TKI - Health & PE

Māori health: te whare tapa whā model

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

CONTENTS

- Background

- Introduction: taha wairua - spiritual wellbeing

- What are Karakia

- Māori spiritual practices

- Māori spiritual concepts

- Tohunga

- Māori prophetic movements

- Spiritual places: the Marae

- Religious belief in New Zealand

- Spiritual places: the church

- Sacred places and objects

- Wāhi tapu

- Spiritual objects

- Spirituality in schools

- Some spiritual and religious festivals

- Supporting resources

- Quick facts

- Glossary

- Symbols of spirituality

- Places of Spirituality

- Wāhi tapu: images of sacred spaces

- Images of spiritual objects

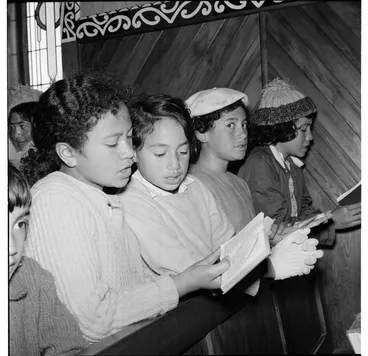

Church service, Torere

Alexander Turnbull Library

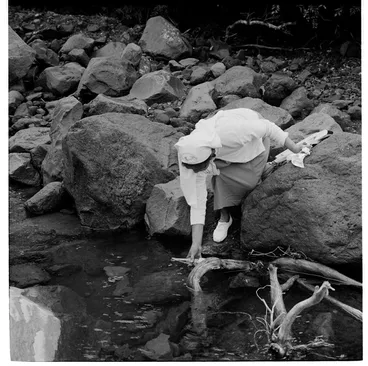

Spiritual healing

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Toko Toru Tapu church, Manutuke

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Church service, Manihiki, Cook Islands

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

INTRODUCTION: TAHA WAIRUA - SPIRITUAL WELLBEING

Inā kei te mohio koe ko wai koe,

I anga mai koe i hea,

kei te mohio koe,

Kei te anga atu ki hea

If you know who you are and where you are from, then you will know where you are going.

The taha wairau component of Hauora refers to the spiritual (religious and non-religious) beliefs and values that determine the identity of a person or community and gives purpose to their actions and lives.

What is Wairau?

Wairua is the spirit of a person. Wairua can leave the body and go wandering. When a person dies it is their wairua which lives on. Traditionally Māori believed that when they died they would go to rarohenga (the underworld). In northern traditions, this involved travelling te ara wairua (the pathway of spirits) to te rerenga wairua (the leaping place of spirits). Wairua would then descend to the sea.

Source: Traditional Māori religion – ngā karakia a te Māori - Spiritual concepts, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

All are one in Jesus Christ

Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand

WHAT ARE KARAKIA?

Karakia are the way people communicate with the gods. Te Rangi Hīroa (Peter Buck) suggested a karakia was ‘a formula of words which was chanted to obtain benefit or avert trouble. Karakia were not used to worship or venerate gods. One type of karakia, a tūā, was a spell.

Source: Traditional Māori religion – ngā karakia a te Māori - Karakia, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

An example of a traditional karakia

Nau mai e ngā huao

te waoo

te ngakina

o te wai tai

o te wai Māori

Nā Tane

Nā Rongo

Nā Tangaroa

Nā Maru Ko Ranginui e tū iho nei

Ko Papatūānuku e takoto nei Tuturu whakamaua

Kia tina! TINA! Hui e! TĀIKI E! I

Translation

Welcome the gifts of food

from the sacred forests

from the cultivated gardens

from the sea

from the fresh waters

The food of Tane

of Rongo

of Tangaroa

of Maru

I acknowledge Ranginui who is above me,

Papatuanuku who lies beneath me

Let this be my commitment to all!

Draw together! Affirm!

Source: What are karakia?

MĀORI SPIRITUAL PRACTICES

Rituals and ceremonies

Because spiritual forces such as mana, tapu and mauri were seen as all-pervasive, people navigated the spiritual world through karakia and ritual. Most ceremonies and rituals required the services of tohunga. Some included:

Tūā

Babies were named after the tāngaengae (navel cord) was severed. The tūā rite was performed in the place where the child was born. It removed the tapu from both the mother and child, and ensured health for the child.

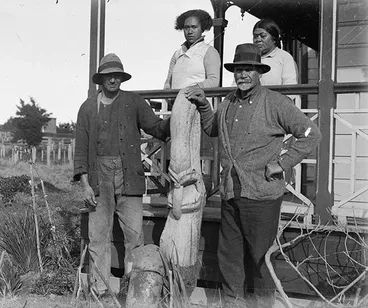

Rāhui

Tapu could be placed on particular places or things to limit people’s access to them. This was called a rāhui. Rāhui might be placed where a person had died. For example if someone drowned, a stretch of water might have a rāhui placed on it by a rangatira or tohunga to prevent it being used for a period.

Source: Traditional Māori religion – ngā karakia a te Māori - Rituals and ceremonies, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

The Māori Christ, Ōhinemutu

Auckland Libraries

Service at site of Turakina Māori Girls' School

Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand

MĀORI SPIRITUAL CONCEPTS

Mana

Mana describes an extraordinary power, essence or presence. It relates to authority, power and prestige. Mana comes from the atua (gods) and is highest amongst rangatira (those of chiefly rank), particularly ariki (first born), and tohunga (experts).

The concept of mana is closely tied to tapu.

Tapu and noa

A person’s tapu is inherited from their parents, their ancestors and ultimately from the gods. Higher born people have a higher level of tapu.

Flora, fauna and objects in the material world could all be affected by tapu. When a person, living thing or object was tapu it would often mean people’s behaviour was restricted.

Noa means ordinary, common or free from restriction or the rules of tapu. Often ceremonies were carried out to remove the influence of tapu from objects or people so people were able to act without restrictions.

Mauri

Mauri is the life principle or vital spark. All people and things have mauri. People placed physical objects in forests as talismans. These embodied the mauri, and were protected.

If people’s mauri becomes too weak, they die.

Source: Traditional Māori religion – ngā karakia a te Māori - Spiritual concepts, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

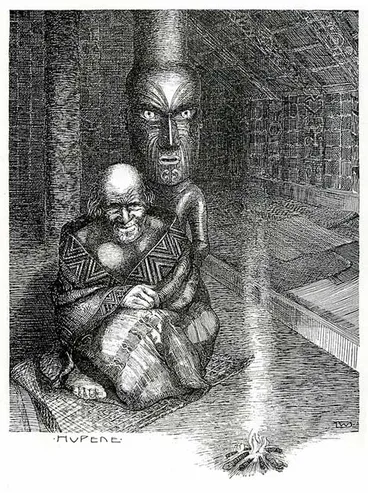

Tohunga

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

TOHUNGA

Priests were known as tohunga. Māori scholar Te Rangi Hīroa (Peter Buck) suggested that the term derives from tohu, meaning to guide or direct. Ngāpuhi elder Māori Marsden suggested tohunga comes from an alternative meaning of tohu (sign or manifestation), so tohunga means chosen or appointed one.

It was the role of tohunga to ensure tikanga (customs) were observed. Tohunga guided the people and protected them from spiritual forces. They were healers of both physical and spiritual ailments, and they guided the appropriate rituals for horticulture, fishing, fowling and warfare. They lifted the tapu on newly built houses and waka (canoes), and lifted or placed tapu in death ceremonies.

Source: Traditional Māori religion – ngā karakia a te Māori - Tohunga, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Tohunga Suppression Act

The Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 was intended to stop people using traditional Māori healing practices which had a supernatural or spiritual element. It was not very effective – only nine convictions were obtained under the act. Whare Taha of northern Hawke's Bay was one of those convicted.

Source: Medicines and remedies - Plant extracts to modern drugs, 1900 to 1930s, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Ratana Church

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

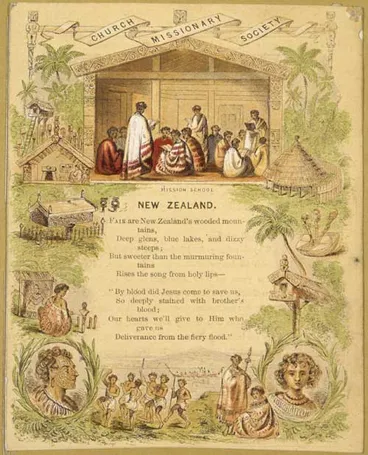

MĀORI PROPHETIC MOVEMENTS

Underlying all Māori prophetic movements was the search for the recovery of Māori authority – te mana motuhake. From Papahurihia to Rua Kēnana, prophetic movements were met with antagonism by land-hungry governments.

Prophecy was part of traditional Māori society. It was practised by tohunga and matakite (seers). As Christianity brought by missionaries took hold, prophets combined Māori and Christian traditions.

Source: Māori prophetic movements – ngā poropiti, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

The Topic Explorer set Māori Religious Movements provides more information on the history and examples of Maori religious movements from early colonial times to the 21st century.

Members at Te Kāhui Whetū, Owae Marae

NZEI Te Riu Roa (New Zealand Educational Institute)

SPIRITUAL PLACES: THE MARAE

The primal atua (gods) Papatūānuku (the earth mother) and Ranginui (the sky father) and their children are symbolised in the layout of the marae and its significance during pōwhiri (welcomes).

The marae ātea, the space outside the front of the meeting house, is the domain of Tūmatauenga (or Tū), the god of war. Speeches that take place on the marae ātea are allowed to be forceful, representing the nature of Tū.

The wharenui (meeting house) is considered to be the domain of Rongo, the god of peace. Speeches that take place within the wharenui are expected to be more conciliatory. Metaphorically, the floor of the wharenui represents Papatūānuku, while the roof represents her husband, Ranginui. Tāne, who separated the two, is metaphorically represented by the building in the phrase, Tāne whakapiripiri (Tāne who draws people together).

Source: Marae protocol – te kawa o te marae - Mythology and history of marae protocol, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Spring flower service

Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand

RELIGIOUS BELIEF IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND

Origins of New Zealand’s religions

New Zealand’s pattern of religious diversity developed out of the religious cultures brought by the communities that migrated to the country. Māori brought religious customs and practices from Polynesia. European missionaries and settlers brought varieties of British Protestantism and French Catholicism. Anglicans, Methodists and Presbyterians shaped the structure, values and traditions of the new society. Almost all Māori adopted forms of Christianity, so New Zealand was regarded as a Christian nation.

21st Century

In the 2010s Christianity remained the largest single religion in New Zealand but there were also sizeable Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim and Sikh communities, each made up of various ethnic and language groups with very different migrant experiences. None was represented by a single organisation. There was sometimes tension between different faith groups, resulting in complex relationships both within and between religious communities.

Source: Diverse religions - Religious diversity in New Zealand, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

New-age spiritual movements

In the 1980s and 1990s groups considering themselves spiritual rather than religious saw the dawning of a new age (‘the age of Aquarius’). The emphasis of these ‘new-age’ groups was on personal transformation and experience rather than dogma, doctrine and hierarchy. Many methods were used, including channelling spirits, gemstones, meditation, reincarnation and past-life techniques, indigenous wisdom, dance, trance and visualisation. These groups were often very fluid and were characterised by workshops, seminars, one-on-one client services, or New Age noticeboards in local spiritual bookshops. New Age fairs have been held in centres around the country.

Source: Diverse religions - Recent and new-age religious movements, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

White Sunday

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

SPIRITUAL PLACES: THE CHURCH

For many, Māori, Pākehā and Pasifika peoples the Christian church provides the most important spiritual base in their lives. The church is not only a place of worship but operates as a dynamic community actively supporting and nurturing its congregation and the wider community.

Pacific churches in the 21st century

In the early 21st century Pacific people were quite religious compared to other New Zealanders. In the 2013 census more than three-quarters of Pacific people said they were Christians, compared with just half of all New Zealanders. Only 16.5% of Pacific people said they had no religion.

The largest Pacific denomination was Catholic, then Presbyterian/Congregational, then Methodist.

Role of churches

In the Pacific Islands, community life was built around the family, the church and the village. In New Zealand, churches acted like villages. The minister was the most powerful and respected person – a role similar to the village chief.

Source: Pacific churches in New Zealand, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

SACRED PLACES AND OBJECTS

Many landscape features in New Zealand/Aotearoa are spiritually important to Māori and therefore need to be treated with cultural respect. They include such features as rivers, lakes, hills, islands, swamps caves and mountains. Specific examples include Waitomo Caves, Wairau Bar, Moturua Island and the Tainui waka landing site at Kawhia harbour.

Because Māori tīpuna – ancestors, created, named or occupied these places today’s tangata whenua are directly linked spiritually to their environment. This is why they also maintain the responsibility of kaitiakitanga (guardianship) of these tapu whenua places.

For example, Māori referred to the Tongariro National Park area as Te Kahui Tupua - the sacred peaks, (Tongariro, Ngauruhoe and Ruapehu). To the Ngāti Tūwharetoa iwi these mountains were so tapu they would avoid looking at them while passing. In 1993, the park was the first in the world listed as a World Heritage landscape site of indigenous spiritual and cultural importance.

Another famous spiritual site is Cape Reinga – the tip of the North Island. For Māori, this is where spirits of the dead leave Aotearoa and journey back to the ancestral homeland of Hawaiki.

Other landmarks and cultural areas are also regarded as spiritually important and sometimes access and behaviour are restricted through the concept of tapu. This includes places like waka landing sites, Māori cave art and urupa – cemeteries. One famous urupa is Mount Taupiri in Waikato. Here and at other urupa, water is provided at the entrance to wash away the tapu after leaving the cemetery.

WĀHI TAPU

Some areas were considered tapu (restricted). These included burial grounds, sites where people had been killed, trees where the whenua (placenta) of children had been placed and the tops of tribal mountains. Certain prohibitions applied to these areas. People either had to stay away from them, or refrain from doing things which would break their tapu, for instance taking food to wāhi tapu.

Source: Traditional Māori religion – ngā karakia a te Māori - Tūāhu and wāhi tapu, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Maori Cemetery, Waimate, South Canterbury, 1999

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Mere Pounamu

Puke Ariki

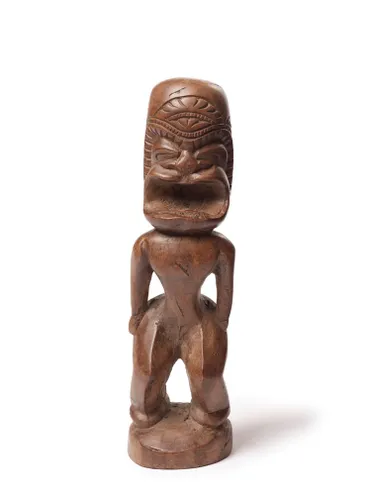

SPIRITUAL OBJECTS

Items and objects can also be imbued with spiritual significance. Examples include:

Taumata atua

Some objects contained atua and were used in ceremonies associated with fertility.

Taumatua atua (abiding place of the gods) were images shaped from stone that were placed near food crops as mauri to protect their vitality.

Whakapakoko atua

Whakapakoko atua or atua kiato (god sticks) were usually carved and had a pointed end so they could be inserted into the ground. They were used as temporary shrines for atua, and were also used to ensure the fertility of crops, or the abundance of fisheries.

Source: Traditional Māori religion – ngā karakia a te Māori - Tūāhu and wāhi tapu, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Pounamu

Pounamu is treasured by Māori because:

- it is strong and beautiful

- it is a sign of status or power

- it is believed to be sacred.

Symbol of a chief

Pounamu weapons were used for fighting, but they were also carried by chiefs to show their high status. They were also used in ceremonies, and sometimes they were given as a symbol of a peace agreement.

These items were treasures. They were often given names and reminded people of stories about their ancestors. Te Āwhiorangi is an adze that is said to have been used by the god Tāne. He used it to cut the bindings that held Ranginui (the sky) and Papatūānuku (the earth) together.

Tribal heirlooms

All tribes have stories of pounamu artefacts. In particular, toki (adzes), mere pounamu and toki poutangata are central in these. These items are often given names, and they are seen as being tapu (sacred) and having great mana (status). They were a talisman to remind people of stories of battles and great events in which their ancestors took part. They were also a physical representation of connection, through whakapapa (genealogy), to venerated ancestors, and the artefacts were often remembered in songs.

Source: Pounamu – jade or greenstone, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

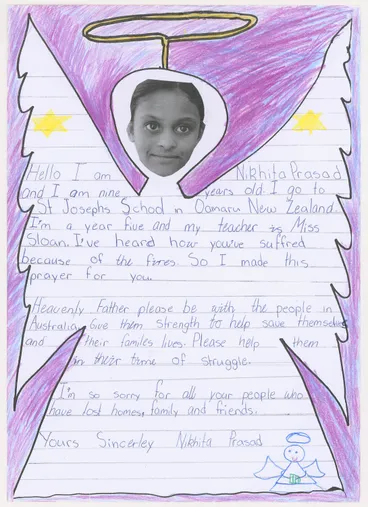

SPIRITUALITY IN SCHOOLS

Examples of classroom practice that could promote or create awareness of spiritual experiences could include:

- Students relating their approach and experiences of spirituality as practised by their whānau and community

- Student’s talking about their interests and passions

- Class set reading of (non-religious) spiritually-themed books or the teacher reading to the class

- Sharing experiences of spirituality that involve concepts of transformation, empathy, courage, compassion and fortitude

- Exploring projects and opportunities to support and explore concepts like manaakitanga, kaitiakitanga and aroha

- Providing mahi tahi opportunities to explore spirituality (like experiences with nature) then using the arts - art, drama, dance and music to articulate these

- Students investing in appropriate national initiatives larger than the school/local community but can be actioned at the local level.

SOME SPIRITUAL AND RELIGIOUS FESTIVALS

Modern Matariki

Traditionally, Māori were keen observers of the night sky, determining from the stars the time and seasons, and using them to navigate the oceans. Lookouts would watch for the rise of Matariki just before dawn. For Māori, this time signified remembrance, fertility and celebration.

Matariki celebrations were popular before the arrival of Europeans in New Zealand, and they continued into the 1900s. Gradually they dwindled, with one of the last traditional festivals recorded in the 1940s. At the beginning of the 21st century Matariki celebrations were revived. Their increasing popularity has led to some to suggest that Matariki should replace the Queen's birthday as a national holiday.

When Te Rangi Huata organised his first Matariki celebrations in Hastings in 2000, about 500 people joined him. In 2003, 15,000 people came. Te Rangi Huata believes that Matariki is becoming more popular because it celebrates Māori culture and in doing so brings together all New Zealanders: ‘It’s becoming a little like Thanksgiving or Halloween, except it’s a celebration of the Māori culture here in (Aotearoa) New Zealand. It’s New Zealand's Thanksgiving.’

Source: Matariki – Māori New Year - Modern Matariki, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Diwali

Diwali or the Festival of Lights is a popular Hindu festival celebrating the victory of light over darkness. In New Zealand, Auckland’s Diwali festival is one of the largest religious festivals. Not only is it a celebration of the Indian New Year but it also highlights and celebrates Indian culture - traditional and contemporary and our Indian communities.

Every year over 60,000 people attend the Auckland Diwali festival. Highlights include traditional dance, Indian cuisine and fireworks. Diwali Festivals are also popular in other large cities with Indian communities like Hamilton, Wellington and Christchurch.

Each year Diwali is celebrated in October or November and the festival lasts for about five days.

Chinese New Year

Over the last 30 or so years as New Zealand has become more multi-cultural there has been a growing recognition and celebration of cultural and spiritual practices that flourish outside of Christianity.

An example is the Chinese New Year. In New Zealand, this 2-week celebration is consistently popular and features such spectacular and vibrant attractions like lantern festivals, dragon dances and firework displays.

The Chinese New Year is also known as the Lunar New Year or Spring Festival, and for Chinese and their families represents their most important festival. In New Zealand, Chinese New Year is celebrated in January and lasts around sixteen days beginning with Chinese New Year and ending with the Lantern Festival.

Spiritually, traditionally and symbolically for Chinese families, the Chinese New Year represents a time to honour and show respect to ancestors and to reaffirm family connections.

Christian celebrations

Easter

Lent (the period of self-denial leading up to Easter), Passion week (culminating in Good Friday) and Easter Sunday involved solemn religious observances for Anglicans and Catholics. New Zealanders of other denominations or faiths welcomed Easter weekend as an autumn holiday.

Traditions such as eating hot cross buns on Good Friday were maintained. Spring symbolism, integral to northern-hemisphere Easter celebrations, was irrelevant in New Zealand, but the custom of eating Easter eggs on Easter Sunday continued, and chocolate Easter eggs were introduced in the early 1900s. In the 2000s both hot cross buns and Easter eggs were on sale for a long period before Easter.

Christmas

Homesick English and Irish settlers missed northern-hemisphere Christmas traditions and tried to maintain them. The Catholic Christmas Eve midnight mass and other church services were well-attended. Christmas trees, a German custom, were introduced to England by Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, and were gradually adopted in New Zealand. Many well-known carols were composed in the 1800s, and carol singing became as popular in New Zealand as it was in the northern hemisphere. Philanthropy and giving of presents continued. Children were the main recipients, especially once the American concept of Santa Claus (better known to New Zealand youngsters as Father Christmas) caught on from the late 1860s.

Source: Public holidays - Easter, Christmas and New Year, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Holi Festival celebration, Long Bay Beach.

Auckland Libraries

Lanterns

Christchurch City Libraries

Christmas decorations at Shirley Library

Christchurch City Libraries

SUPPORTING RESOURCES

Books — spiritual children's books to read with kids.

Free kids books — books with a spiritual theme to read or download.

Human Rights Commission Religion in New Zealand schools, questions and concerns — schools must not discriminate against their students on the grounds of religious belief or lack of it but there are a number of ‘traps for the unwary’.

Key Pacific Health Models in New Zealand: the Fonua model - “The concept of ‘health’…means the well being of the whole person: that is his/her spiritual, mental and physical well being, which is an interpretation that is consistent with the Pacific’s holistic worldviews."

Meditation — why meditation should be taught in schools.

New Zealand religions — a look at the many religions operating in New Zealand society.

Religions — religion can be explained as a set of beliefs concerning the cause, nature, and purpose of the universe, often containing a moral code governing the conduct of human affairs.

Schools of thought — can mindfulness lessons boost child mental health?

Sixteen children’s books — for ‘spiritual but not religious’ families.

Spiritual concepts of the Maori — for Māori there were 3 aspects to a person’s spirituality, body, soul, and spirit or — tinana, mauri, and wairua.

Spirituality — spirituality means different things to different people.

Things we believe make us Kiwi — friendliness and a can-do attitude top a list of traits that New Zealanders think reflect our national identity.

Understanding New Zealand national identity — national identity is a form of social identity – meaning people’s understanding of who they are in relation to others.

Wairua — a poem about who we are.

Kindergarten children saying grace before eating during a party at Karori West School, Wellington

Alexander Turnbull Library

QUICK FACTS

- Spirituality is a word with many definitions, but the word’s origin comes from the Latin noun spiritualitas, which means to breathe.

- A contemporary definition of spirituality is the search of purpose and meaning in life and the values, and actions one uses to achieve that purpose.

- A saint is a religious person who is generally recognised to have demonstrated exceptional holiness or closeness to their God.

- A secular saint is an inspiring respected leader (not necessarily religious) who has made a remarkable and positive contribution to the world. An example would be the American civil rights campaigner Martin Luther King Jr.

- Some examples of spiritual techniques used today are meditation, self-reflection, contemplation, solitary retreats, pilgrimage and prayer.

- Hauora, the Māori concept for wellbeing, has a strong emphasis on spirituality which is seen as a natural, integral part of te ao Māori.

- In New Zealand some spiritual practices which are frequently seen are pōwhiri, observing a rahui and washing hands after visiting a cemetery.

- In many kura kaupapa Māori, Māori bilingual (and other) classrooms, saying karakia (often at the start of the day) is a common practice.

- For Māori reciting one’s whakapapa is seen as spiritually significant because it honours tīpuna and acknowledges a personal identity to the past.

- Similarly, the wharenui is a spiritual house because it symbolises, traces and celebrates collective identity and community.

- Other cultural spiritual expressions of Māori identity can be found in whaikōrero, kapa haka, and waiata.

Pou rāhui

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

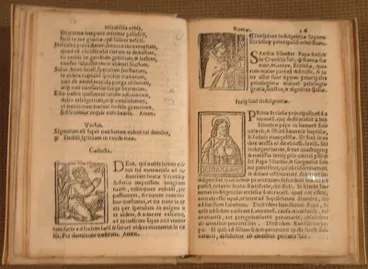

Church Missionary Society hymn

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Rāhui sign

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

GLOSSARY

Definitions below have been taken from Te Aka.

karakia — incantation, ritual chant, chant, intoned incantation, charm, spell - a set form of words to state or make effective a ritual activity.

mahi tahi — to work together for a goal or the implementation of a task.

rāhui — to put in place a temporary ritual prohibition, closed season, ban, reserve.

tohunga — skilled person, chosen expert, priest, healer - a person chosen by the agent of an atua and the tribe as a leader in a particular field because of signs indicating talent for a particular vocation.

wāhi tapu — sacred place, sacred site - a place subject to long-term ritual restrictions on access or use, e.g. a burial ground, a battle site or a place where tapu objects were placed.

pōwhiri — invitation, rituals of encounter, welcome ceremony on a marae, welcome.

tīpuna/tūpuna — ancestors, grandparents - plural form of tipuna and the eastern dialect variation of tūpuna.

whaikōrero — to make a formal speech.

wairua — spirit, soul - spirit of a person which exists beyond death. It is the non-physical spirit, distinct from the body and the mauri.

wairuatanga — spirituality.

SYMBOLS OF SPIRITUALITY

Christmas Tree

Christchurch City Libraries

Cross on chain necklace

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

rosary beads

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

Buddha

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

PLACES OF SPIRITUALITY

Becks Presbyterian Church 26 May 2002 R0005

Central Otago Memory Bank

Romanian Orthodox Church, Wellington

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Ratana temple

Alexander Turnbull Library

Buddhist temple, Flat Bush, 2008

Auckland Libraries

Tibetan Buddhist meditation at Lake Pūkaki

Christchurch City Libraries

Opaea Maori Church, Taihape

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

WĀHI TAPUl: IMAGES OF SACRED SPACES

Mt Tongariro

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Waikato River

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Mt Taranaki (Mt Egmont)

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Sea cave at Mōkau

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Cape Rēinga

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Location of the Tainui canoe at Kawhia

Auckland Libraries

Burial service, Taupiri, 2011

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

[Sacred stone of Kawakawa]

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

Ratana gathering near Dawson Falls, Easter - drinking the sacred water

Alexander Turnbull Library

Tapu puriri

Auckland Libraries

Site of battle of Te Ranga

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

IMAGES OF SPIRITUAL OBJECTS

Whakapakoko atua

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Taumata atua

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Taylor, Richard, 1805-1873 :[Maori god stick. 1840-1850s]

Alexander Turnbull Library

Mere Pounamu

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

God figure carving

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Hei tiki

Puke Ariki

Spiritual guides

University of Otago

This story was curated and compiled by Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, July 2020.

![[Sacred stone of Kawakawa] Image: [Sacred stone of Kawakawa]](https://images.digitalnz.org/ecpAiH5TIzPLSHJv3O7eoF33OtE=/368x0/https%3A%2F%2Fcollection-api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Frecords%2Fimages%2Fmedium%2F672835%2Ff1cb80eb1b2a9c7391678bbdd030c219923958a1.jpg)

![Taylor, Richard, 1805-1873 :[Maori god stick. 1840-1850s] Image: Taylor, Richard, 1805-1873 :[Maori god stick. 1840-1850s]](https://images.digitalnz.org/nW94fzU5UnYrbFZL25mi0-sqcWg=/368x0/https%3A%2F%2Fndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz%2FNLNZStreamGate%2Fget%3Fdps_pid%3DIE180124)