Erebus air crash in Antarctica

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library Services to Schools

On 29 November 1979, an Air New Zealand sightseeing aircraft crashed into the side of a volcano in Antarctica, killing everyone on board. This story follows the events of New Zealand's worst disaster in aviation history.

Erebus disaster, air disasters, New Zealand disasters, Man-made disasters, Antarctica, Air New Zealand, Social Sciences

A dark smudge on the white slopes of Mt Erebus – photo taken by Bob Thomson, 2 days after the accident

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

THE EREBUS AIR CRASH DISASTER

Background

When Air New Zealand first considered operating flights to Antarctica in the late 1960s, the airline discussed the conditions it would need to meet with the Ministry of Transport's Civil Aviation Division (CAD). It was unclear if flights would be economically viable under these conditions, and the airline deferred its plans until it had replaced its DC-8 fleet. The first of its new DC-10s arrived in 1973, enabling the airline to make flights over the icy continent and return to New Zealand without landing, eliminating costs such as the need to provide of passenger facilities at McMurdo Station.

Source: 'Antarctic flights', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/antarctic-flights, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 16-Sep-2019

Contents

This story on the Erebus air crash contains the following:

- The popularity of the flights

- The briefing on 9 November 1979

- What changed in the coordinates?

- Air New Zealand Flight TE901 take off from Māngere Airport – 28 November 1979

- Final communication

- The crash confirmed

- Recovery operations

- The investigation

- Time-honoured memorials

- The delayed apology

- Quick facts

- Glossary

- Other resources

Antarctic flights

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Checking in for an Antarctic Flight

Antarctica New Zealand

Iceberg trapped in sea ice at Cape Hallett

Antarctica New Zealand

The popularity of the flights

The popularity of these flights, and positive reports from passengers, meant Air New Zealand needed to do little advertising to fill the seats on those it announced for November 1979. The airline offered an appealing package: meals and refreshments, a complimentary bar service, in-flight entertainment and expert commentary.

Source: 'Tourist flights to Antarctica', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/erebus-disaster/visiting-antarctica, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 12-Sep-2019

Meltpool icicles at Cape Hallett

Antarctica New Zealand

Albatross on nest

Antarctica New Zealand

Antarctica

Antarctica New Zealand

The briefing on 9 November 1979

On 9 November 1979, Captain Jim Collins and First Officer Greg Cassin, members of the flight crew rostered on Air New Zealand's 28 November Antarctic flight, attended a route qualification briefing. This covered the instrument flight rules (IFR) route to the McMurdo area, which stipulated a minimum instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) altitude en route of 16,000 ft.

They were also advised of a visual meteorological conditions (VMC) let-down procedure which permitted them to descend to 6000 ft over McMurdo if visibility was good. Material presented at the briefing, including printouts of a flight plan used for a previous trip, gave the impression that the IFR route would take them down McMurdo Sound over flat sea ice.

Source: 'Timeline to disaster', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/erebus-disaster/crash-of-flight-901, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 19-Sep-2019

TERMINOLOGY

Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC): conditions that normally require pilots to fly under instrument flight rules (IFR). IFR are regulations and procedures for flying aircraft by referring only to the aircraft instrument panel for navigation. Most scheduled airline flights operate under IFR.

Visual Meteorological Conditions (VMC) are conditions in which pilots have sufficient visibility to fly the aircraft under visual flight rules (VFR). VFR are regulations for flying aircraft in conditions clear enough for the pilot to see where the aircraft is going. They are often used for sightseeing flights.

Source: 'Erebus flight briefing', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/erebus-flight-briefing, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 16-Sep-2019

Erebus flight briefing

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

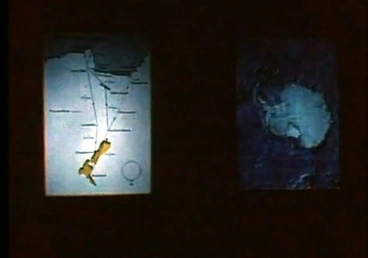

What had changed in the coordinates?

In the early hours of 28 November, a navigational coordinate in the flight plan presented at the briefing was changed. The airline’s navigation section believed it was making a minor adjustment to the flight’s long-standing destination point, but a typing error 14 months earlier meant it had actually shifted this point 27 nautical miles to the east. Instead of the IFR route taking Flight TE901 over sea ice, as Collins and Cassin had been briefed, it would take them directly over Mt Erebus, a 3794-metre active volcano. The flight crew were not alerted to the change. On the morning of 28 November they received the adjusted flight plan and entered these coordinates into the onboard computer.

Source: 'Timeline to disaster', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/erebus-disaster/crash-of-flight-901, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 19-Sep-2019

Air New Zealand Flight TE901 takes off from Māngere airport - 28 November 1979

Shortly before 8.30 a.m. NZDT* on 28 November 1979, Air New Zealand Flight TE901 left Māngere airport, Auckland, for an 11-hour return flight to Antarctica. During the journey south TE901 communicated with the air traffic control centre in Auckland (Oceanic Control Centre) before switching to the United States Navy's air traffic control centre at McMurdo Station, Antarctica (Mac Centre) at approximately 11 a.m. NZDT.

As TE901 made its way south past via the Balleny Islands and Cape Hallett, passengers were treated to a champagne breakfast, lunch and three films: Amundsen - explorer, The big ice and 140 days under the ice. There was also plenty of reading material, including copies of the airline's domestic and international in-flight magazines, and a brief history, Antarctic fragments. Some of this material made for chilling reading in the aftermath of the tragedy - a 16-page photographic booklet described Mt Erebus as the 'sentinel of McMurdo' and referred to McMurdo Sound as a 'coast of bleak beauty'.

Source: 'Antarctic experience slide show', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/interactive/antarctic-experience, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 19-Sep-2019

Iceberg McMurdo Sound

Antarctica New Zealand

Balleny Islands: Black Island

Antarctica New Zealand

Maintenance Base at Mangere International Airport, Auckland

Alexander Turnbull Library

Final communication

The McDonnell-Douglas DC-10 was scheduled to arrive over Antarctica between 12 and 1 p.m. NZST, and from around noon it had ongoing contact with both 'Mac Centre', the United States Navy's air traffic control centre at McMurdo Station, and the 'Ice Tower' at nearby Williams Field. At 12.45 p.m. NZST Cassin advised Mac Centre that the aircraft was at 6000 ft in the course of descending to 2000 ft in VMC. This was the final communication from TE901. Four minutes and 42 seconds later, at 12.49 p.m. NZST, the aircraft crashed into the lower slopes of Mt Erebus, killing all on board.

Source: 'Timeline to disaster', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/erebus-disaster/crash-of-flight-901, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 19-Sep-2019

McMurdo Station

Antarctica New Zealand

Williams Field - Mount Erebus in the background

Antarctica New Zealand

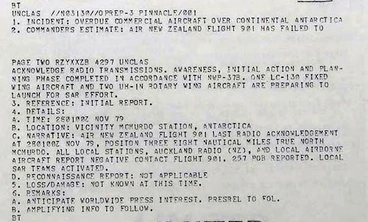

Radio contact lost with Flight TE901

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

The crash confirmed

If they hadn't already heard the news, those arriving to meet disembarking passengers at Māngere airport quickly learned something was wrong - the arrivals board directed them to ‘check with airline'. Air New Zealand airport manager Don Murray issued a statement explaining that the flight had been radio silent for a number of hours and would by now have run out of fuel. Shortly before 10 p.m. Air New Zealand's public affairs director, Craig Saxon, issued a statement in which the airline accepted that the ‘aircraft must be down'.

Confirmation that there were no survivors came later that day after three New Zealand mountaineers, Keith Woodford, Hugh Logan and Daryl Thompson, were lowered onto the crash site by US Navy helicopters. At 12.23 p.m. NZDT Mike Hatcher, the Press Liaison Officer at the Operation Deep Freeze base in Christchurch, issued a brief statement confirming that ‘everybody that was on that aircraft has died’.

Source: 'Hearing the news', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/erebus-disaster/hearing-the-news, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 19-Sep-2019

Bob Thomson describes scene of Erebus crash

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

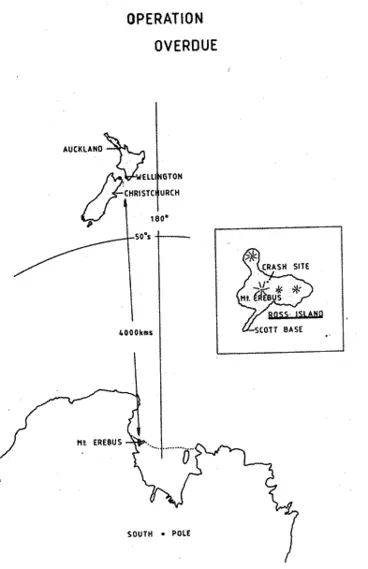

Recovery operations

In the hours that followed the sighting of the wreckage of Air New Zealand's Antarctic Flight TE901, professionals and volunteers around the country learned that they were required to head, assist or report on the site investigation and recovery operation. Many of those working at Scott Base and McMurdo Station would provide invaluable assistance to the investigation and recovery parties.

The first party left Christchurch on the day after the crash. It included the chief air accident investigator, Ron Chippindale, who led the site investigation, and the Police search and rescue coordinator, Inspector Robert (Bob) Mitchell, who led the recovery operation.

Source: 'Operation Overdue', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/responding-to-tragedy/erebus-1979, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 12-Sep-2019

Plane wreckage on Mt Erebus

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Recovering the flight recorders from Erebus

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

THE INVESTIGATION

On 30 November US Navy helicopters flew Chippindale, Mitchell and other key members of the party to view the crash site. They subsequently agreed on priorities.

Poor weather delayed progress until the afternoon of 2 December. Then, as agreed, two surveyors, members of the investigation team, and their mountaineer assistants were flown to the site. Their priority was to find the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and the digital flight data recorder (DFDR), both of which were located within a few hours.

The break in the weather allowed the first members of the Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) team to leave from McMurdo. Deteriorating weather initially hampered efforts to get the remaining team members up to the site, and a blizzard that evening halted work until early the following day.

By 10 December the site investigation and recovery operation in Antarctica was complete.

OPERATION OVERDUE

The victim identification phase of Operation Overdue was headed by Chief Inspector Jim Morgan of the DVI team, which included other police, fingerprint experts, pathologists, photographers, dentists, funeral directors and embalmers, and representatives of Air New Zealand (to help identify the cabin and flight crew).

THE CHIPPINDALE REPORT

After the site investigation in Antarctica was complete, Ron Chippindale and his investigators returned to New Zealand to continue their work. Chippindale's enquiries also took him to the United States and the United Kingdom in late December 1979 and early January 1980.

In the days prior to the release, Chippindale advised the media that he had had difficulty finding 'the ultimate cause'. His report indicated what he thought was the 'probable cause - the last thing that made the accident inevitable' − but other factors had led up to the accident.

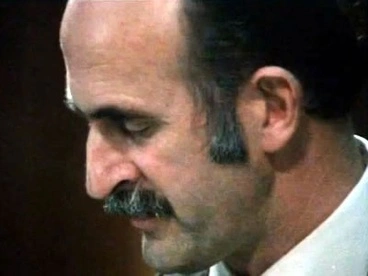

THE MAHON REPORT

Mahon had been due to make his report to the Governor-General by 31 October, but he was granted four extensions to this deadline. At the conclusion of the public hearings he had 3083 pages of evidence, 284 documentary exhibits and 368 pages of closing submissions to review. His report was submitted on 16 April 1981 and released publicly on 27 April.

In a section summarising 'the cause of the disaster', Mahon argued that 'the occurrence of any accident was normally due to the existence of a variety of factors'.

He disagreed with Chippindale's 'probable cause' that the pilot was at fault, and cleared the crew of any responsibility for the accident. Instead he laid the blame squarely on Air New Zealand.

Source: 'Finding the cause', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/erebus-disaster/inquiry, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 29-Nov-2019

Chippindale report into Erebus disaster

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Peter Mahon

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

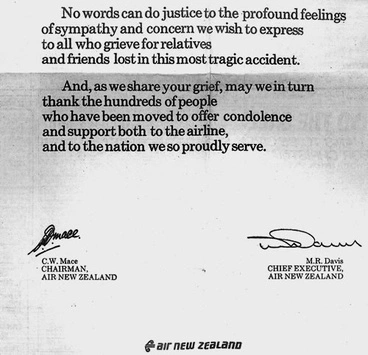

TIME-HONOURED MEMORIALS

After confirmation was received that no one had survived the crash of Flight TE901, expressions of sympathy began to arrive from around New Zealand and the world. Queen Elizabeth II, Prime Minister Rob Muldoon, and Air New Zealand management and staff were among the many who publicly expressed their feelings of sympathy to the victims’ family and friends.

Source: 'Remembering Erebus', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/erebus-disaster/remembering-erebus-disaster, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 27-Nov-2019

This story was compiled and curated by Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, in June 2020.

Erebus memorial at Kihikihi

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Memorial koru with Erebus in background

Antarctica New Zealand

Dedication of the Erebus memorial

Antarctica New Zealand

THE delayed APOLOGY

On 23 October 2009, Air New Zealand CEO Rob Fyfe apologised to those the airline had let down in the aftermath of the tragedy. But for many this apology did not go far enough. Maria Collins, the wife of Captain Jim Collins, the pilot of Flight TE901, told the media that she still hoped to clear her husband's name.

At an event to mark the 40th anniversary of the disaster the Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, and the chair of Air New Zealand, delivered an apology.

Source: 'Finding the cause', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/erebus-disaster/inquiry, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 29-Nov-2019

Air NZ apologises to Erebus families

Radio New Zealand

QUICK FACTS

- The real cause for the Erebus air disaster has never been confirmed.

- Because of daylight saving time, there was an hour difference between New Zealand Daylight Time NZDT) and the time at McMurdo Station in Antarctica. Scott Base and McMurdo Station began observing daylight saving in the summer of 1992/93.

- The 1979 Air New Zealand DC10 on Mt Erebus (even though this occurred outside New Zealand) with the loss of 257 lives is regarded as New Zealand’s worst air disaster.

- The Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand sets air safety standards.

- The first air accident in New Zealand occurred in 1899 when a hot-air balloon landed in the sea, drowning balloonist David Mahoney.

- A Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) is a black box that records all noise and flight crew conversation in the cockpit.

- The Flight Data Recorder (FDR) is a black box that records the operating data (airspeed, altitude, vertical acceleration etc) from the plane’s system.

- The commissioner of the Royal Commission of Inquiry Peter Mahon published a book Verdict on Erebus, which gave his version of the events.

- Besides the Chippendale Report and Mahon Report that dealt with the causes of the air crash, there was another investigation led by Capt Gordan Vette who did not believe that the cause of the crash was pilot error.

- Air tourism became popular in the 1950s after the Second World War when American soldiers stationed in New Zealand chartered planes to have an air view of the beauty spots of South Island.

Close up of Erebus memorial wreath

Antarctica New Zealand

Erebus disaster memorial windows at St Matthew's

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Flight TE901

Antarctica New Zealand

Koru in the Snow

Antarctica New Zealand

Four Members of the DC10 Commission

Antarctica New Zealand

GLOSSARY

Definitions below have been taken from the Oxford Lerner’s Dictionary

black box — a small machine in a plane that records all the details of each flight and is useful for finding out the cause of an accident.

briefing — a meeting in which people are given instructions or information.

complementary — given free.

deferred — to delay something until a later time.

disembarking — to leave a vehicle, especially a ship or an aircraft, at the end of a journey.

embalmer — a person whose job is embalming bodies. (Embalm — to prevent a dead body from decaying by treating it with special substances to preserve it).

pathologists — a doctor who studies pathology and examines dead bodies to find out the cause of death.

subsequently — afterwards; later; after something else has happened.

sentinel — a soldier whose job is to guard something.

stipulated — to state clearly and definitely that something must be done, or how it must be done.

surveyors — a person whose job is to examine and record the details of a piece of land.

OTHER RESOURCES

CVR transcript Air New Zealand Flight 901 — A transcript made available for educational purposes by Aviation Safety Network.

Erebus disaster — The page from Many Answers will guide you to reviewed websites and databases on the Erebus disaster of 1979.

Erebus – The Fate of Flight 901 — Vaughan Yarwood’s piece on the air crash encompasses a huge amount of information from the gathering of passengers to what followed in the aftermath of the crash. Read this article from New Zealand Geographic, available through EPIC. School login maybe required.

Erebus – the loss of TE901 — A website that is dedicated to telling the story of the accident. It includes a timeline of events, personal accounts from the recovery operation and a gallery of images to document this air disaster.

Erebus Voices by Bill Manhire — The Mountain, a poem on the 40th anniversary of the Erebus disaster.

Flight 901 - The Erebus Disaster — The first documentary on the air disaster covers the Antarctica scenic flights, the search and rescue operation and the conflict of views that arose from the Royal Commission of Inquiry.

Mount Erebus — Telephone interview with the widow of the Mount Erebus Air Crash DC10 pilot, who gives her reaction to the Royal Commission of Inquiry report.

Passenger Plane Crashes in Antarctica — Find out why this Air New Zealand DC-10 aircraft crashed into Mount Erebus, the second highest volcano in Antarctica.

White silence: The tragic story of the Air Zealand jet that flew into Mt Erebus, killing all 257 people on board.

Lynch, James, 1947-:Shooting season opens. 4 May 1981

Alexander Turnbull Library

Heath, Eric Walmsley, 1923- :[Morrison Davis being ousted from Air New Zealand's nest]. 5 May 1981.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Daughters of Erebus

Radio New Zealand

Message from the Chairman and Chief Executive of Air New Zealand

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Police map shows the crash site of flight TE901

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Recovery work in blizzard conditions

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

This story was compiled and curated by Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, in 2019.