Parihaka through lens of William Collis

A DigitalNZ Story by Zokoroa

Parihaka captured in photographs by William Collis - before, during and after the invasion on 5 Nov 1881 by government troops

Parihaka, Taranaki, William Collis, Photography, Resistance, Pacificism, History

Parihaka symbolises a significant political, cultural, and spiritual event in Aotearoa New Zealand's history – the meeting of atrocity and injustice with peaceful resistance. Images by photographer William Andrews Collis record the resilience and continuity of the community through the actions of its people.

Parihaka villagers wearing white feathers & carrying poi, 1890s (Photographer: William Andrew Collis)

Alexander Turnbull Library

1. WHO WAS PHOTOGRAPHER WILLIAM COLLIS?

William Andrew Collis (1853 - 1920) had a photography studio in New Plymouth and he travelled around Taranaki and other NZ places photographing people and scenery. He was born in Fiji in 1853 to William and Mary Collis. His father was a Wesleyan missionary teacher based at Lakeba. When the family moved to New Zealand, Collis was educated at Wesley College.

In 1869, at 16 years of age, Collis began his training with Hartley Webster, a New Plymouth photographer. He started working in a studio on Brougham Street in 1875, and then built his own studio on Devon Street in 1882. He was married in 1878, and he and his wife Lydia had six children.

William Collis (1853-1920) had a photography studio in New Plymouth which he built in 1882

In 1869, at 16 years of age, Collis had begun his training with Hartley Webster, & began working in a studio in 1872

Alexander Turnbull Library

Collis' interests included conservation and he was involved with the Egmont National Park Board, the local Scenery Preservation Society, and the Ancient Order of Foresters. Collis was also chairman of the New Plymouth school committee for several years. He served on the New Plymouth Borough Council for varying intervals totalling 18 years between 1898 - 1920, including five years as Deputy Mayor.

Collis on New Plymouth Borough Council (Back row: 2d on right)

Auckland Libraries

2. COLLIS VISITED PARIHAKA, 1875-1910

During 1875 to 1910, William Collis visited Parihaka which was an unfortified Māori village (Pā) located between Mount Taranaki and the coast. He was there the day British troops invaded to arrest the village leaders for campaigns against the government's land surveyors and roadbuilders. That event which took place on 5 November 1881 has become known as the 'Day of Plunder' whereby the village's buildings and crops were destroyed. Collis also visited Parihaka in later years when the village was being rebuilt.

Collis' images, along with those of other photographers and graphic artists, record the resilience and continuity of the community through the actions of its children and adults.

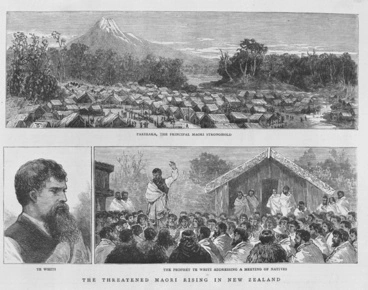

Collis' view of Parihaka Pa, Taranaki, circa 1870s. Mount Taranaki can be seen in the background.

Alexander Turnbull Library

################################################

2a. Collis' photos pre-Invasion

Origin of Parihaka:

One tradition has Parihaka as originally being a village called Rameda which was renamed Parihaka. Following the 1863 Suppression of Rebellion Act and the New Zealand Settlements Act, large areas of Taranaki and Waikato land had been confiscated by the government. The village was sited on confiscated land. In the mid-1860s it became known as Parihaka - it was to be a sanctuary of peace for those that had been dispossessed of their land until the government allocated promised land reserves.

Parihaka was sited on land confiscated following 1863 Suppression of Rebellion Act & New Zealand Settlements Act

It was to be a sanctuary for those dispossessed of their land until the government allocated promised land reserves

Alexander Turnbull Library

PARIHAKA LEADERS: TE WHITI AND TOHU:

The Parihaka villagers were led by Te Whiti-o-Rongomai III and Tohu Kākahi who were of Te Ātiawa (also known as Ngāti Awa and Ngātiawa ) and Taranaki descent. They were related with Tohu being a cousin of Te Whiti's father. Te Whiti and Tohu had attended a Christian mission school in Wārea and were baptised as Christians. They drew on their ancestral and Christian teachings to advocate for Māori ownership of their lands and to live in peaceful partnership with Pākehā settlers. Many Māori came to their monthly meetings to hear their preachings of self-determination, temperance and peaceful resolution of land issues.

The Parihaka villagers were led by Te Whiti-o-Rongomai III & Tohu Kākahi who were of Ngāti Awa & Taranaki descent

They had attended a Christian mission school in Wārea & were baptised. Tohu was a cousin of Te Whiti's father.

Auckland Libraries

WEARING OF WHITE FEATHERS:

The wearing and holding of white feathers, as seen in Collis' photos, symbolise the wearers were followers of Te Whiti. He had promoted wearing three white feathers of the albatross. The number three signified “the glory to God, peace on earth, goodwill toward people” (Luke 2:14).

"Some descendants believe Tohu and the people of Parihaka saw an albatross descending onto the village, symbolising the sanction of the Holy Spirit on the growing movement at Parihaka, and on the two men who were to lead it. A feather was left behind by the albatross, and Tohu's marae at Parihaka was called Toroanui (great albatross). Others believe the vision was celestial – a trail of light from a comet in the shape of a feather. The raukura, the single albatross feather, was adopted as a symbol protecting the mana of the Parihaka movement."

Source: Danny Keenan. 'Te Whiti-o-Rongomai III, Erueti', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1993, updated November, 2012. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2t34/te-whiti-o-rongomai-iii-erueti

Wearing of white feathers symbolised the wearers were followers of Te Whiti

The three feathers signified “the glory to God, peace on earth, goodwill toward people.” (Luke 2:14)

Alexander Turnbull Library

GROWTH OF PARIHAKA:

The population of Parihaka was reported to have increased from 300 in 1871 to over 1500 by the end of the 1870s. When Taranaki's Medical Officer visited in 1871, he reported Parihaka was the cleanest, best-kept pā he had ever visited and its inhabitants "the finest race of men I have ever seen in New Zealand". Food was seen to be in abundance, good cookhouses were in use, and there was an absence of disease. (Source: Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 31–38)

When journalists visited Parihaka in October 1881, they found "square miles of potato, melon and cabbage fields around Parihaka; they stretched on every side, and acres and acres of the land show the results of great industry and care". The village was described as "an enormous native town of quiet and imposing character" with "regular streets of houses". (Source: Te Taranaki Report: Kaupapa Tuatahi by the Waitangi Tribunal, chapter 8.)

Collis' panorama of Parihaka, ca. 1881

Depicts Te Whiti's house centre of the image.

Puke Ariki

CAMPAIGN AGAINST SURVEYORS & ROAD BUILDERS:

In February 1879 the Government started surveying land for settlement. However, the surveyors did not first mark out reserves promised by the Crown officials for Māori occupation. When disagreements arose over agreed boundaries, Te Whiti, Tohu and their neighbour Titokowaru arranged peaceful acts of resistance - men were organised to pull out survey pegs and plough the land.

Te Whiti had maintained to the settlers that the ploughing was not directed against them, but were actions of protest to assert their rights and force the Government to outline land policy. However, many settlers were concerned and threatened to shoot the ploughmen and their horses and bullocks. As a consequence, the Crown began to arm large number of volunteers and located Armed Constabulary officers around the Taranaki district.

Collis visited the Taranaki sites where the Crown had located Armed Constabulary officers

Alexander Turnbull Library

Armed Constabulary station, Pungarehu, Taranaki

Alexander Turnbull Library

Volunteer camp, Rahotu, Taranaki

Alexander Turnbull Library

In June 1879, Governor Grey instructed that any ploughmen whose actions were likely to lead to a disturbance of the peace would be arrested. When the ploughmen were arrested for being on ‘government land', they did not resist, and were replaced with more unarmed workers.

In early 1880, the Crown sent forces to build a coastal road through the Parihaka district. When fences were pulled down, Te Whitu and Tohu sent fencers to rebuild them. Crown forces began to arrest the fencers on 19 July 1880.

Members of the 'Wellington Navals' at Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

Fort Rolleston, Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

TROOPS ASSEMBLE OUTSIDE PARIHAKA DURING 1881

By 1881, Parihaka had attracted more than 2000 inhabitants. For several months during 1881, troops had surrounded the Parihaka village as Te Whiti continued to protest against the village’s fields being surveyed for settlers.

Lieutenant-Colonel J.M. Roberts (front row, third left) with Armed Constabulary officers

NZ Armed Constabulary at Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

Volunteers in Camp, Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

################################################

2B: Collis' photos of PARIHAKA INVADED BY CROWN'S TROOPS: 5 NOV 1881

On 19 October 1881, Native Affairs Minister Rolleston signed and 'published all over the colony' a proclamation giving the Parihaka people 14 days in which to submit to the law of the Queen or risk the loss of all their lands. That same day, he stepped down from his ministerial role and was replaced by his predecessor John Bryce. The Government then decided to charge Te Whiti with sedition after hearing of a speech he had delivered at a hui.

On 5 November 1881, around 1589 armed constabulary and volunteers led by Lieutenant-Colonel John Mackintosh Roberts and the Native Affairs Minister, John Bryce, invaded Parihaka. They had orders to arrest Te Whiti for continually protesting against the village’s fields being surveyed for settlers.

Armed constabulary awaiting orders to advance on Parihaka Pa

Alexander Turnbull Library

BUT THERE WAS NO FIGHTING:

Tohu had gathered the people on Toroanui marae to restrict troop movement throughout the unarmed village. Those troops that arrived at the entrance were greeted whereas hospitality was withheld from the troops that arrived at the rear of the village. Children with white feathers sang waiata, performed haka, and played with skipping ropes. Women offered loaves of bread, whilst seated nearby were over 2000 villagers. They had chosen to ‘fight’ violence with peace. The pathway of peaceful resistance shown by the children, women and men had been instilled by Te Whiti and Tohu.

After the reading of the Riot Act, Te Whiti and Tohu were arrested

Puke Ariki

TE RĀ O TE PĀHUA' OR THE DAY OF PLUNDER:

Native Affairs Minister Bruce ordered the destruction of the village and the dispersal of the villagers. Buildings were pulled down or burnt and the contents looted by the troops. Farming machinery and crops were destroyed. The livestock was driven away or slaughtered. Men were arrested and 1600 villagers expelled. For Taranaki Māori, this day in Aotearoa’s history is known as 'Te Rā o te Pāhua' or the 'Day of Plunder'.

Buildings were burnt or pulled down, & farm machinery & crops destroyed

Alexander Turnbull Library

1600 villagers were expelled, & animals driven off or slaughtered

Alexander Turnbull Library

################################################

2C. Collis' photos of rebuilding of Parihaka following release of Te Whiti & Tohu in March 1883

After eighteen months imprisonment, Te Whiti and Tohu returned to Parihaka in March 1883.

"Te Whiti and Tohu were finally permitted to return to Taranaki in March 1883; with some indignity, they were driven the last few miles to Parihaka in an open cart. Parihaka, in their absence, had fallen into neglect. The extensive damage inflicted by the invading constabulary had been left unrepaired. Meetings were prohibited, but protest activity continued. One commentator reported that Te Whiti's mana had increased with his absence, and that his persecution was likened to that of Christ. Te Whiti commenced a series of visits to other villages, but these were soon abandoned."

Source: 'A return to peace', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/titokowarus-war/a-return-to-peace, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage)

Some 5,000 acres of the promised reserve at Parihaka were taken by the Crown as compensation for the costs of its military activities at Parihaka. To rebuild the community, Te Whiti introduced Pākehā refinements of electricity and plumbing that both he and Tohu had seen in the South Island when taken on a guided tour during their imprisonment.

The modifications were done with financial assistance from Rāniera Ellison and Taare Waiatara. Rāniera Tāheke Ellison of Ngāti Moehau, a hapū of Te Ātiawa, had moved south to hunt for gold in the early 1860s. He was living at Ōtākou near Dunedin where Parihaka villagers had been imprisoned in 1882. He had met Te Whiti and Tohu during their guided South Island tour. Financial support and supervisory assistance was provided by Taare Waiatara (1854-1910) of Te Ātiawa who moved to Parihaka in the 1880s from Wellington. Taare used resources from his extensive land holdings in the Wellington area to finance projects. He became the son-in-law of Te Whiti marrying his daughter Perani Ngaruaki when he was aged 36.

Group outside a cookhouse in Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

Unidentified people outside a whare on the Parihaka Pa

Alexander Turnbull Library

Collis, William Andrews, 1853-1920 : Maori group at Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

Te Whiti engaged tradesmen to instruct the villagers on carpentry, plumbing, electrical work, blacksmithing, butchering, road-building, and land cultivation. Teams of workers were supervised by Taare. He financed the provision of clean water via ‘an ingenious water supply system’ and made other sanitary reforms. (Source: Rachel Buchanan, The Parihaka Album: Lest We Forget (Wellington, 2009), p. 134)

The rebuilding programme included a slaughterhouse, bank, prison. and a large Victorian mansion 'Te Raukura', which also included a bakery and chambers for Te Whiti and his rūnanga (council).

Rebuilding programme included housing, slaughterhouse, bank and prison

Housing included a large Victorian mansion "Te Raukura" which included a bakery & chambers for Te Whiti & his council

Alexander Turnbull Library

Dining room with lighting fixtures hanging from the wall

Alexander Turnbull Library

The Te Niho dining hall can be seen on the left

Te Whiti's marae is in the background. The large house to the right is Rangi Kapua.

Alexander Turnbull Library

RIFT DEVELOPED BETWEEN TOHU AND TE WHITI:

During the rebuilding of Parihaka's facilities, unlike Te Whiti, Tohu preferred not to be influenced by European ways and supported their earlier policy of self-sufficiency.

"A number of Te Whiti's more conservative followers transferred their allegiance to Tohu at this time. Thereafter, visiting Pākehā gravitated to the European side of the village in search of the 'chief' of Parihaka, rather than to the older whare where Tohu still lived... Tohu continued to resist the introduction of alcohol into Parihaka, counselled his people to stay out of debt, and denounced taxes which he felt were being levied unfairly against them."

Source: Ailsa Smith. 'Tohu Kākahi - Tohu Kakahi', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1993. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2t44/tohu-kakahi

Those who followed Tohu were the Ngatiruanui, called Pore (pulled or dehorned or unhorned) because they ceased the wearing of the raukura or white albatross feather emblem of Te Whiti's people. Te Whiti led the Maire (Horned) Ngatiawa tribe. Source: 'Burial of a Maori chief', Otago Witness, 13 Feb 1907

Tohu's carved whare

Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago

MORE ARRESTS OF PLOUGHMEN, 1897:

In 1897, ninety-two Māori were arrested for ploughing in protest at long delays in the resolution of issues pertaining to the management of native reserves by the native trustee.

Group welcoming the returning prisoners to Parihaka on 17 July 1898

Alexander Turnbull Library

Return of the ploughman prisoners, Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

Women performing a poi dance, Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

PARIHAKA DESCRIBED AS A MODEL VILLAGE, 1899:

The outcome of the rebuilding of Parihaka, as described by the Hawkes Bay Herald (31 March 1899. p.2), was "A model village, which would be a credit to any European community". Parihaka’s modernised conveniences included a piped water supply from a reservoir, hot and cold water, and a drainage system. It also had a generator for electricity before bigger towns and cities, including Wellington.

Parihaka was described as a "model village"

A generator was used for electricity before bigger towns and cities, including Wellington

Auckland Libraries

Modern conveniences included a piped water supply from a reservoir, hot & cold water & drainage system

MOTAT

CULTURAL PRACTICES, 1880S-1890S:

When William Collis revisited Parihaka in the 1890s, this group of children and adults had been rehearsing haka and poi dances. The wearing and holding of white feathers symbolise they were followers of Te Whiti. The children and adults continued to be instructed in traditional cultural practices by their tutor Taare (Charles) Waitara and others.

Group of childen and adults had been rehearsing haka and poi dances when photographer Collis visited

Their tutor, Taare (Charles) Waitara, is standing in the middle

Alexander Turnbull Library

The image above by Collis provides a window into our past. It helps us to visualise the actions taken by another group of children during the earlier event known by Taranaki Māori as 'Te Rā o te Pāhua' or the 'Day of Plunder'. It also records the rebuilding of Parihaka with this new generation of children guided by Taare and others.

Group about to perform a haka at Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

Te Whiti had resisted setting up a Native School although a national system of village primary schools had been established under the Native School Act 1867. He wanted a mix of traditional Māori knowledge and Christian theology to continue to be taught, without having an overriding influence of European values, cultural practices, and language. As seen in Collis' photographs, the children and adults have continued to wear white feathers, which have come to symbolise peace.

Taare Waitara and haka party, Parihaka, 1890s

Alexander Turnbull Library

Taare Waitara and haka party, Parihaka, 1890s

Alexander Turnbull Library

SYMBOLISM OF POI:

The poi was adopted by Te Whiti as an emblem symbolising peace and hospitality. "The poi dance was more than a mere amusement in Parihaka. It was a semi-religious ceremony; the ancient songs centuries old were chanted, and Te Whiti's speeches were recorded in a kind of musical Hansard and given forth in high rhythmic song to the multitude at those periodical gatherings." Source: James Cowan, Hero stories of New Zealand: Te Whiti of Taranaki - the story of a patriot and peacemaker. Harry H. Tombs, 1935, p.245. http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-CowHero-t1-body-d32.html#name-100311-mention

Poi dancing, Parihaka

Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago

FIFE & DRUM BAND:

After a brass band from Whanganui visited Parihaka around 1898, Taare (Charles) Waitara formed a fife and drum band. Initially, the band played English songs and escorted visitors into Parihaka. Later it was used for accompanying poi songs.

Fife and drum band at Parihaka Pa

Alexander Turnbull Library

Members of a brass band, and others, outside the house of Charles Waitara, at Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

Fife and drum band, Parihaka Pa, Taranaki

Alexander Turnbull Library

Band of flute and drum players, and others, outside the house of Charles Waitara, at Parihaka

Alexander Turnbull Library

MONTHLY GATHERINGS ATTENDED BY MĀORI & EUROPEANS:

Te Whiti and Tohu held a forum each month called Tekau mā waru (‘The Eighteenth’) which still takes place on the 18th and 19th of each month. Both Māori and Europeans were welcome.

Collis photographed the meeting held during March 1896 where Te Whetu called for the rich to be taxed

Alexander Turnbull Library

Utauta Wi Parata was younger sister of Ngauru who'd married Te Whiti's son Nohomairangi

Alexander Turnbull Library

TOHU DIED ON 4 FEBRUARY 1907:

Tohu was buried without a coffin, according to his teachings, and his grave at Parihaka remains unmarked. After Tohu's death his followers voted against rejoining Te Whiti. They organised their own religious meetings at Ketemarae in southern Taranaki, and at places along the Whanganui River, where Tohu's teachings are observed to this day. Source: Ailsa Smith. 'Tohu Kākahi - Tohu Kakahi', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1993. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2t44/tohu-kakahi)

Te WHITI DIED ON 18 NOVEMBER 1907:

Te Whiti died nine months after Tohu on 18 November 1907. Taare supervised the building of the tomb for Te Whiti. At the tangi, Taare spoke: "Let peace be upon all. Let it be understood that Te Whiti had only one word, one way, one raukura, the white feather, which is the sign that all nations throughout the world will be one. This feather will be the sign of unity, prosperity, peace and goodwill." Source: Leo Fanning, "The dramatic tangi of Te Whiti O-Rongomai". New Zealand Founders Society Bulletin, no. 30, June 1964, p.2)

Symbolism of Parihaka:

Te Whiti and Tohu's vision and teachings preceded non-violent movements, such as those led by Mahatma Ghandi, Martin Luther King, and Rosa Parks. The story of the people of Parihaka has resonated around the world as a struggle for peace for all peoples. The raukura – white feather – has become a symbol of Parihaka’s passive resistance movement promoting unity, prosperity, peace, and goodwill.

In 2017, the Crown was again met at Parihaka with singing children wearing white feathers. This time the occasion was the Crown delivering a formal apology for its actions over Parihaka. It acknowledged its failure to honour its obligations to Taranaki Iwi under Te Tiriti o Waitangi / the Treaty of Waitangi (1840). The apology or Te Pire Haetaki Parihaka (Parihaka Reconciliation Bill) was passed into law on 24 October 2019.

###############################################

3. PORTFOLIO OF RANGE OF IMAGES BY COLLIS:

Photographs taken by William Andrews Collis provide a visual historical record of the events that unfolded at Parihaka. A collection of 517 images of the Taranaki district, including Parihaka, were donated to the Alexander Turnbull Library by the New Plymouth Library and Museum in July 1948. For other examples of Collis' work accessible on DigitalNZ, see the following selection of portraiture and scenic photographs.

Unidentified Group of Men

Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago

Elsdon Best - Photograph taken by William Andrews Collis

Alexander Turnbull Library

Port Moule W

Air Force Museum of New Zealand

Unidentified Group of Women

Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago

Portraits included child studies

Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago

Portrait of two unidentified children - Photograph taken by William Andrews Collis

Alexander Turnbull Library

Travelled around Taranaki taking portraits

Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago

Photographed sights in New Plymouth & surrounding area

Alexander Turnbull Library

Also visited Rotorua & other places

Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago

Illustration of the gunboat Pioneer off Meremere

Alexander Turnbull Library

An unidentified man with a rifle

Alexander Turnbull Library

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT WILLIAM COLLIS:

- Early New Zealand photographers and their successors: William Andrews Collis. https://canterburyphotography.blogspot.com/2012/01/collis-w.html

- Wiki Tree: William Andrew Collis (1853 - 1920): https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Collis-221

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT PARIHAKA:

- James Cowan, Hero stories of New Zealand: Te Whiti of Taranaki - the story of a patriot and peacemaker. Harry H. Tombs, 1935, pp. 236-245 http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-CowHero-t1-body-d32.html#name-100311-mention

- James Cowan, The New Zealand Wars: A history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period: Vol II. Wellington: R>E> Owen, 1956, pp.23-25 http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cow02NewZ-c2.html

- Danny Keenan. 'Te Whiti-o-Rongomai III, Erueti', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1993, updated November, 2012. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2t34/te-whiti-o-rongomai-iii-erueti

- NZ History: Te Whiti: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/people/erueti-te-whiti-o-rongomai-iii

- 'Report from Joseph Orton', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/report-joseph-orton, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 25-Jun-2014

- Riseborough, Hazel, ‘A New Kind of Resistance: Parihaka and the Struggle for Peace.’ Contested Ground: Te Whenua I Tohea. The Taranaki Wars, 1860-1881. Ed. Kelvin Day. Wellington: Huia, 2010. 230-253.

- Dick Scott, Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann, 1975. pp. 31–38

- Ailsa Smith. 'Tohu Kākahi - Tohu Kakahi', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1993. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2t44/tohu-kakahi