Māori History Post-European Arrival

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library of New Zealand Topics

The arrival of Captain Cook initiated a dynamic but increasingly unequal relationship between Māori and Pakeha through colonialism. From the Treaty of Waitangi and the New Zealand Wars to land marches and Treaty settlements this topic explores a history of Māori post-European arrival and their response to colonisation. SCIS no: 1894418

Māori Women's Welfare League Conference

Alexander Turnbull Library

Māori Women’s welfare league

Services to Schools

Māori Women's Welfare League

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Strutt, William 1825-1915 :A group I once saw in Maori Land. New Plymouth. 1856

Alexander Turnbull Library

Māori Party co-leaders, 2008

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Maori Party marks 10th anniversary

Radio New Zealand

Mete Kingi Te Rangi Paetahi - Photograph taken by Edward Smallwood Richards

Alexander Turnbull Library

First Māori MPs

Services to Schools

Māori–Pākehā relations

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

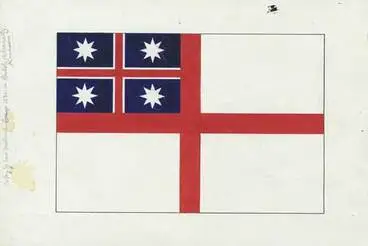

Kiingitanga flags: Mahuta's flag

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Tupara (double-barrelled shotgun).

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Maori woman from Hawkes Bay district

Alexander Turnbull Library

Maori man from Hawkes Bay

Alexander Turnbull Library

Pioneer Women - Princess Te Puea

NZ On Screen

Koha - Whina Cooper (Part One)

NZ On Screen

Role of Māori newspapers

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Ngā rōpū tautohetohe – Māori protest movements

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

The first Kotahitanga movements, 1834 to 1840

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Kotahitanga leader Hōne Heke Ngāpua

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Repudiation movement

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Destiny Church service

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Ngā tohu – treaty signatories

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Parihaka

DigitalNZ

Kororāreka painting

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Williams, John, d 1905 :War dance, N.Z. 1858.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Creator unknown: Reproduction of painting captioned "Oihi Bay, Christmas Day 1814"

Alexander Turnbull Library

English & Continental Photographers (Nelson) fl 1880s : Portrait of Huria Matenga

Alexander Turnbull Library

Maori Battalion training at Maadi, Egypt

Alexander Turnbull Library

Māori women smoking pipes

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Hawbridge, Bob, fl 1890s:The Latest New Woman. New Zealand Graphic, 9 February 1895. p. 131.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Rua Kenana

Alexander Turnbull Library

Pioneer Battalion, First World War

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

North Island influenza death rates - The 1918 influenza pandemic

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

The wars of Waitara - Roadside Stories

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Urbanisation

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Māori renaissance

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Dog Tax War narrowly averted

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Native school, Whangapē

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

New work explores the history of wāhine Māori

Radio New Zealand

Early NZ Maori

DigitalNZ

Native report

Services to Schools

Research and the colonisation of Māori knowledge

Services to Schools

The invasion of Parihaka

Services to Schools

A mature nation owns its history

Services to Schools

Ōrākau, famed battle site

Services to Schools

Place-based education and Māori history

Services to Schools

Concerns over how NZ history is taught

Services to Schools

Tūhoe history

Services to Schools

The Māori tribes of Taranaki

Services to Schools

Colonising and decolonising the Māori mind

Services to Schools

Racism row in Gisborne council

Services to Schools

Ngāi Tahu – the iwi

Services to Schools

Impacts of colonisation on modern Māori culture

Services to Schools

Lost in translation

Services to Schools

Our Taonga

Services to Schools

The New Zealand Wars

Services to Schools

The 1975 Land March

Services to Schools

Te Ao Māori

Services to Schools

Māori history

Services to Schools

Colonisation in Aotearoa New Zealand

Services to Schools

200-year-old Māori drawings to go on loan to UK

Services to Schools

Smoothing the pillow of a dying race

Services to Schools

Māori history video

Services to Schools

Growing interest in remembering Taranaki's land war history

Services to Schools

Māori maps

Services to Schools

Te ao Māori: The synergy between women and the land

Services to Schools

Who are Tūhoe?

Services to Schools

History of Māori in Auckland

Services to Schools

New Zealand wars

Services to Schools

Māori land ownership

Services to Schools

Māori history

Services to Schools

Ngā rōpū – Māori organisations

Services to Schools

Māori and the First World War

Services to Schools

The Māori Land March

Services to Schools

The Native Rights Act, 1865.—No. 3 - New Zealand: Acts affecting Native Lands, 1886, 1888-91 and 1894-95

Victoria University of Wellington

The 28th Māori Battalion

Services to Schools

Re-enactment of NZ Wars in Bay of Islands.

Services to Schools

Māori history

Services to Schools

Wiremu Tamihana

‘Surrendering’ to General Carey in 1865 at Tamahere near present-day Hamilton, Wiremu Tamihana (and others who fought against Pakeha) were quick to learn their battles were only just beginning in seeking redress for land confiscation by colonial Pakeha. Letters, petitions, delegations and hui attempting to seek the return of Maori land met largely with indifference and empty promises from Pakeha who through legislation (like the notorious New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 ) proceeded to undertake confiscation (raupatu) of Waikato (and other) lands. In the 1880s there was even a petition to Queen Victoria that came to nothing.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Native schools

Native schools begin with the creation of the 1867 Native Schools Act. The following year saw 17 schools operating and a few others receiving supplementary assistance. By 1955 the number had risen to 166. Although these were referred to as Native, or later, Māori schools, the curricular emphasis was very much on assimilation – the teaching and learning of English and colonial ideals. In fact, Māori children could be (and were) punished for speaking te reo Māori at school. That changed somewhat from the 1930s when the policy of assimilation became more relaxed.

Alexander Turnbull Library

The Orakau battle resulted in over 150 Maori deaths and signalled the end of the Waikato war. Many Maori were killed when they abandoned the pa en-masse and attempting to escape towards the Puniu river. In the 1922 book Te Awamutu, the story of the Waipa Valley… author James Cowan quotes an army chaplain who recounts the battle and the Maori heroism which has subsequently become mythologised. “We have officers here who fought through the Crimea and the Indian Mutiny; all unite in affirming that neither the Russians nor the Sepoys ever fought as the Maoris have done; all lament the necessity of having to fight against such a gallant race. On this point the whole army is unanimous.”

Sketch of the country about Orakau

National Library of New Zealand

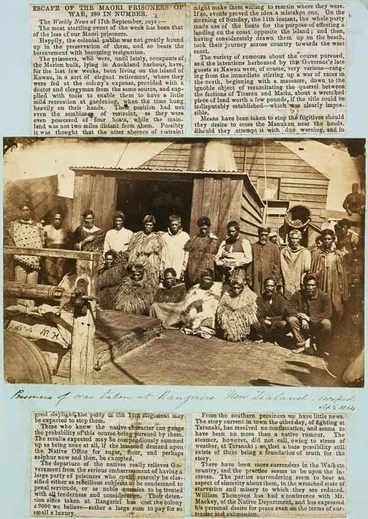

Maori prisoners of war

Twenty-four Māori men (some obscured) are standing and seated mainly in two rows aboard the prison ship (hulk) Marion in Auckland Harbour. They are dressed in a mixture of Māori and European clothing. A news clipping surrounding the photograph is headed, 'Escape of the Maori prisoners of war, 200 in number' copied from the Weekly News of 17 September 1864. The prisoners escaped in boats from Kawau Island, their place of imprisonment after being aboard the Marion. Remarkably some of the prisoners later in life stated that their escape from Kawau Island was arranged by the then Governor Sir George Grey and some local chiefs on condition of good behaviour.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Trial of Te Whiti

Te Whiti’s 1886 trial in Wellington was reported widely around the country. At the trial, one spectator noted that Te Whiti held himself more like a “King being tried by rebellious subjects than an ordinary native charged with riot.” He was also described as appearing “to be between fifty-five and sixty years of age, with hair tinged with grey and iron grey whiskers of the medium length.” Hundreds of Europeans and Maori had gathered to get a glimpse of Te Whiti, and Titokowaru before they were both driven off in the prison van to Wellington’s Terrace Gaol. After Te Whiti formally bade farewell to his people outside the court he disappeared into the van. “The others followed him in silence.”

Alexander Turnbull Library

Carved door with the coat of arms for the Maori kings

While the mid-year celebration of Matariki and the symbolism of its 7 stars (the seven daughters of Matariki) are now well-known in New Zealand. What isn’t so well-recognised is that the Kiīngitanga (Maori King movement) adopted the stars of Matariki as a symbol or coat of arms for its movement many years ago. A striking example of this is the carving on the door of the Māhinārangi meeting house on the Tūrangawaewae marae, in Ngāruawāhia. Matariki symbolises not only the Maori New Year but a new beginning – a perfect symbol for the Kiingitanga movement. A similar example was the Maori newspaper Te Paki o Matariki which ran from 1892 to around 1935.

Alexander Turnbull Library

The day after Waitangi

In the first frame titled 1840, a thoughtful or even apprehensive Pakeha official clutches a document as a Maori chief smiles and puts his arm round his shoulder. In the second frame, the situation is neatly reversed. A thoughtful (or again apprehensive) Maori holds a laptop while a smiling Pakeha man has his arm draped over his shoulder. One context for this cartoon is that in 1840 Maori believed the Treaty of Waitangi had given them full partnership, participation and protection. Fast forward to 2011 and the country is now dominated by non-Maori. The Pakeha believes he has got the better deal and the Maori is not so sure Maoridom has been fully recognised and reimbursed.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Whina Cooper and Tame Iti

This photograph shows two of Maoridom’s most widely known activists together leading the famous 1975 Maori Land March through Hamilton/ Kirikiriroa. Carrying the pou whenua is a young Tame Iti. He is almost unrecognisable with his long hair and without his signature moko that many today associate him with. On his left is Whina Cooper who more than once has been referred to as ‘the Mother of the Nation.’ As a leader of the 1975 protest hikoi she took the march from Te Hāpua in Northland to Parliament in Wellington demanding an end to selling off Māori land. Prior to this however, Dame Whina Cooper had led a very full, active and at times controversial life in her Northland community.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Storybook app: Turikatuku — Te wahine taki wairua

Services to Schools

E-Tangata: History

Services to Schools

The Māori king visits Auckland

Services to Schools

Study of carved axe handle

There are many examples of everyday items that Māori embellished with carving. This one (others include paddles and firearms) is an axe handle. It has been ornately carved, leaving just enough space for the hand to grip the axe. Māori used axes or tomahawks both as a weapon and a tool.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Te Rauparaha

This full length sketched portrait of the famous warrior chief, Te Rauparaha, was made in 1848. Appropriately for someone who was sometimes called Napoleon of the South, it shows the Ngati Toa leader wearing a cocked hat and military tunic and trousers. In 1848 when this sketch was done Te Rauparaha had just been released from imprisonment. He subsequently spent time in Otaki supervising the construction of the famous Māori church, Rangiātea. It is claimed that over 1,000 Māori assisted in the church’s construction. Te Rauparaha died at Otaki the following year.

Alexander Turnbull Library

A group of six Māori

This staged photograph shows a group of six Māori (one wearing Pakeha clothing) and an unidentified male European. It possibly includes Hariata and Hare Pomare in the centre. Hariata and Hare Pomare were part of a tour party that visited England in the 1860s. While there, Hariata Pomare gave birth to a son, Albert Victor. Albert was the first Māori born in England. He also became Queen Victoria's godchild!

Alexander Turnbull Library

Letter from Arekatera Te Weraomahuta

This is a letter (and contemporary translation) by Arekatera Te Weraomahuta to Te Waka (a Maori Newspaper.) It urges Maori to end war, become united under the one law and take advantage of the economic benefits because, “the natives have no chance to cope with any European race.” There were a number of newspapers written for a Maori audience from the 1840s. Some were produced by the government, and some initiated by Maori. There were also religious newspapers.

Alexander Turnbull Library

'Mother of the Nation' Dame Whina Cooper immortalised at Panguru

Services to Schools

History of Aotearoa podcast

Services to Schools

Timeline of Māori newspapers

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Setting aside the Moriori myth

Services to Schools

Maui Solomon - the negotiator

Services to Schools

Te Hau Kāinga - The Māori Home Front

Services to Schools

Two New Zealands: The 2,700 day gap

Services to Schools

Tongariro National Park - A Gift to the People of New Zealand

Services to Schools

Treaty of Waitangi

DigitalNZ

Kiingitanga

DigitalNZ