Hauora: Taha Whānau - Social Wellbeing

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library Services to Schools

Taha whānau goes beyond family wellbeing to include relationships with friends, colleagues and in the community. This story covers the importance of taha whānau, what groups we belong to, and how to strengthen and maintain healthy relationships.

Me mahi tahi tatou mō te oranga o te katoa.

We should work together for the wellbeing of everyone.

Members of a new mothers' group get together to support women as they face the first challenges of parenthood.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

BACKGROUND

The World Health Organisation defines health as :

Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

Today we know for a fact that each of these aspects of health is as important as the other, and can profoundly impact each other.

In New Zealand, hauora (health) takes a holistic view beyond just physical wellbeing. According to Te Whare Tapa Whā Māori model of health developed by Māori health expert Mason Durie, there are four walls and a floor that contribute to overall health and wellbeing. These are:

- Taha hinengaro — mental and emotional wellbeing

- Taha whānau — social wellbeing

- Taha tinana — physical wellbeing

- Taha wairua — spiritual wellbeing

- Taha whenua — connection with the land and environment wellbeing.

Māori health: te whare tapa whā model

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Taha whānau or social wellbeing focuses on belonging to various groups, the importance of social wellbeing and is benefits as one of the five cornerstones of wellbeing.

CONTENTS

This story on taha whānau contains the following:

- What is taha whānau - social wellbeing?

- The importance of taha whānau

- The sense of belonging for taha whānau

- Social organisations -Whānau we belong to:

- Families in New Zealand

- Tribal organisations

- Whakapapa — ancestry

- School

- Community groups

- Religion and spiritual groups

- Hoamahi - colleagues

- Teams

- Strengthening taha - whānau:

- Social support

- Sense of belonging

- Empathy

- Stand against bullying

- Quick facts

- Glossary

- Supporting resources

- A gallery of images that reflects the diverse range of cultures that people belong to in Aotearoa New Zealand

WHAT IS TAHA WHĀNAU - SOCIAL WELLBEING?

Here are some definitions of social wellbeing:

Taha whānau is about who makes you feel you belong, who you care about and who you share your life with.

Whānau is about extended relationships – not just immediate relatives. It’s your hoamahi/colleagues, friends, community and the people you care about. You have a unique place and a role to fulfil within your whānau and your whānau contributes to your wellbeing and identity.

The capacity to belong, to care and to share where individuals are part of widersocial systems.

Whānau provides us with the strength to be who we are. This is the link to our ancestors, our ties with the past, the present and the future.

Understanding the importance of whānau and how whānau (family) can contribute to illness and assist in curing illness is fundamental to understanding Māori health issues.

Having a meal together shows a social connection.

Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand

THE IMPORTANCE OF TAHA WHĀNAU

Social connections play an important role across many aspects of people’s lives, from finding employment and getting advice on important decisions, to receiving support during difficult times and having someone to enjoy life and relax with.

Social connectedness is a key driver of wellbeing and resilience. Socially well-connected people and communities are happier and healthier and are better able to take charge of their lives and find solutions to the problems they are facing.

Ministry of Social Development (MSD)

THE SENSE OF BELONGING FOR TAHA WHĀNAU

A sense of belonging, connectivity and relationships are at the heart of taha whānau and this comes from:

- who you belong to,

- who makes you feel you belong,

- who you care about and

- who you share your life with.

SOCIAL ORGANISATIONS — WHĀNAU WE BELONG TO:

FAMILIES IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND

The traditional Pākehā idea of the family is the nuclear family – mum, dad and their children. But there are many different kinds of families in New Zealand.

- Māori whānau include people of several generations (e.g. grandparents, parents and children) who are related by descent or marriage. They may or may not live together in the same house but share a strong sense of connection.

- Extended-family households may include several generations – children, parents and grandparents. These are more common among Māori, Pacific and Asian households.

- Sole-parent families are usually the result of parents separating or children being born to mothers who live alone.

- Families with lesbian or gay parents may have children from a previous relationship, or children conceived through donor sperm or with a surrogate mother.

- In blended families adults and children who have been part of other families come together to form a new family, often after separation or divorce.

Source: Diverse families, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Untitled Portrait of the Wimperis Family

Dunedin Public Art Gallery

Hare Family Group

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

Given family portrait

Auckland Libraries

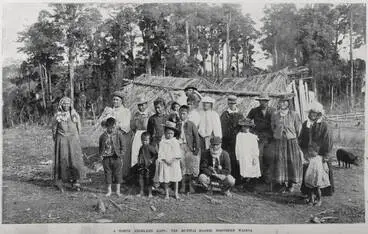

MĀORI WHĀNAU

Māori whānau traditionally:

- were a family group of parents, grandparents, children and uncles and aunts

- lived in the same buildings

- worked together to support the whole whānau

- had common ancestors.

Although not many people live like this now, whānau ties are still very strong.

Individual members of whānau are encouraged to express themselves, and the strength of the whānau is the contribution that all the individuals make.

Whānau can be ‘whānau ake’ the immediate family, or a whole extended group of great grandparents, cousins, uncles and aunts and children and grandchildren.

People who have died, or ex-partners of divorced people, are still seen as whānau members.

Whānau is also used as a name for friends, or for a group with a common purpose.

Source: Whānau – Māori and family, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Whenuaroa whānau

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Whanau display at Shirley Library

Christchurch City Libraries

Pūtiki Wharanui Pā, Whanganui

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

TRIBAL ORGANISATIONS

Iwi

The largest political grouping in pre-European Māori society was the iwi (tribe). This usually consisted of several related hapū (clans or descent groups). The hapū of an iwi might sometimes fight each other, but would unite to defend tribal territory against other tribes.

Iwi-tūturu (the homeland tribe) or tino-iwi (the central tribe) were groups living in a long-held location. They would take their name from a founding ancestor. Iwi-nui or iwi-whānui (the greater tribe) were groups tracing descent from the founding ancestor of the iwi-tūturu. They were often widespread and lived alongside people from other iwi.

Source: The significance of iwi and hapū — Tribal organisation, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Iwi newspapers

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Iwi aquaculture

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Awa and iwi

Science Learning Hub

Hapū

The most significant political unit in pre-European Māori society was the hapū. Hapū ranged in size from one hundred to several hundred people, and consisted of a number of whānau (extended families). Hapū controlled a defined portion of tribal territory. Ideally, territory had access to sea fisheries, shellfish beds, cultivations, forest resources, lakes, rivers and streams.

Many hapū existed as independent colonies spread over a wide area and interspersed with groups from other iwi. The viability of a hapū depended on its ability to defend its territory against others; in fact the defence of land was one of its major political functions.

Source: The significance of iwi and hapū — Tribal organisation, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

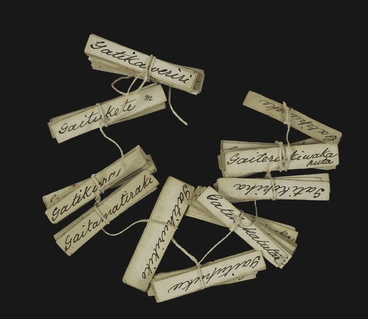

W. B. D. Mantell, Names of the hapu of the Kai Tahu tribe

University of Otago

A North Auckland Hapu: The Mititai Maoris, Northern Wairoa

Auckland Libraries

Rangitāne Partnership Agreement Signing

Palmerston North City Library

WHAKAPAPA — ANCESTRY

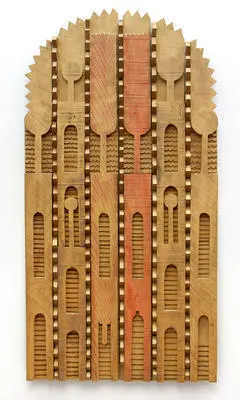

Whakapapa is genealogy, a line of descent from ancestors down to the present day. Whakapapa links people to all other living things, and to the earth and the sky, and it traces the universe back to its origins.

Whakapapa are told orally in different ways. The most common is tararere, which gives a single line of descent from an ancestor, without marriage partners or other kin. A short whakapapa giving just the names of important ancestors is known as tātai hikohiko or āhua hikohiko.

Source: Whakapapa — genealogy, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Maniapoto's whakapapa (genealogy) recited

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Rākau whakapapa

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Whakapapa is the core of traditional mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge). Whakapapa means genealogy. Other Māori terms for genealogy are kāwai and tātai. Kauwhau and taki refer to the process of tracing genealogies.

East Coast elder Apirana Ngata explained that whakapapa is ‘the process of laying one thing upon another. If you visualise the foundation ancestors as the first generation, the next and succeeding ancestors are placed on them in ordered layers.’1

Source: What is whakapapa? — Whakapapa — genealogy, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Whakapapa III

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

Kūmara whakapapa

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

SCHOOL

A Core Education White Paper in 2016 stated that a learner's socio-emotional wellbeing is crucial for learning to take place. This was supported by the Education Review Ofice that identified a direct connection between belonging and learning:

Although there is not a single measure for student wellbeing, the factors that contribute are interrelated and interdependent. For example, a student’s sense of achievement and success is increased by a sense of feeling safe and secure at school and, in turn, affects their resilience. (ERO)

Kelly-Ann Allen from Monash University says a sense of belonging in school is important for wellbeing. Here are some of the reasons why:

- It helps students to build their identity.

- Develops psychosocial skills.

- Influence by peer groups.

- Shaping future relationships and interactions

- Aids academic performance and aspirations.

- Develops positive self-esteem and resilience.

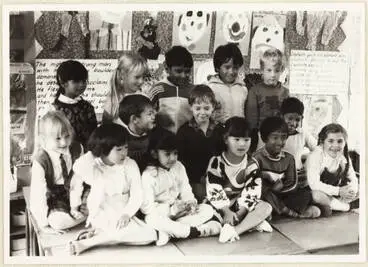

Multicultural classroom, Pukekohe Hill School, ca 1987

Auckland Libraries

Entertaining Her Friends On The School Bus, Seven-Year-Old Julia Lissington Practises Her Violin On The Way Home

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

Christchurch Korean Community School

Christchurch City Libraries

KŌHANGA REO, KURA AND WĀNANGA

In traditional Māori society, all important aspects of life had systems of knowledge transfer and skills acquisition that had been refined over the centuries. The learning process began in the womb, with mothers chanting oriori (lullabies) to their unborn children. When a child was born, tohunga would undertake rituals to prepare them for their future role within the iwi.

As children grew, it was crucial to the survival and success of the hapū and iwi that they learnt a positive attitude to work, and practical activities such as gathering, harvesting and preparing food, and weaving, carving and warfare.

The whare wānanga (house of learning) was a traditional educational institution reserved for a select few with the proper chiefly lineage.

Source: Education in traditional Māori society — Māori education – mātauranga, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Kōhanga reo (preschool language ‘nests’) led the way in the 1980s, followed by kura kaupapa Māori (Māori-language immersion schools).

Kura kaupapa Māori are state schools that operate within a whānau-based Māori philosophy and deliver the curriculum in te reo Māori.

Wānanga are Māori tertiary institutions developed by Māori to revitalise te reo Māori and mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge), and to raise the achievement of Māori in tertiary education.

Source: Kaupapa Māori education — Māori education — mātauranga, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Kura kaupapa Māori

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Awanuiārangi graduation

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Mahitaone kōhanga reo

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

COMMUNITY GROUPS

Social connections play an important role across many aspects of people’s lives, from finding employment and getting advice on important decisions, to receiving support during difficult times and having someone to enjoy life and relax with.

Social connectedness is a key driver of wellbeing and resilience. Socially well-connected people and communities are happier and healthier, and are better able to take charge of their lives and find solutions to the problems they are facing.

Ministry of Social Development (MSD)

According to the Ministry of Social Development, three common components of social connectedness can be identified as :

- socialising,

- social support,

- sense of belonging.

Hester Roa and his band playing Filipino folksongs and Original Pilipino Music (OPM)

Christchurch City Libraries

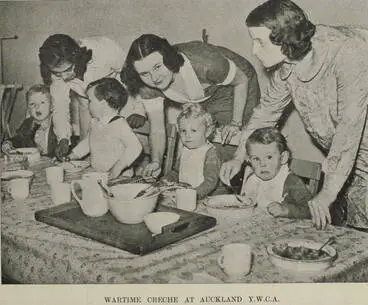

Wartime creche at Auckland Y.W.C.A.

Auckland Libraries

Pottery class, Pakuranga, 1980.

Auckland Libraries

The Young Māori Party was formed by former pupils of Te Aute College. They wanted tribes to undergo social and health reforms.

During the Second World War, tribes came together in the Māori War Effort Organisation. The 28th Māori Battalion was organised on a tribal basis.

After the war, many people moved from tribal areas to cities. The Māori Women’s Welfare League was formed in 1951. Its members helped people adjust to life in the cities.

The New Zealand Māori Council, established in 1962, took some landmark cases to court about Māori rights under the Treaty of Waitangi.

Source: Ngā rōpū — Māori organisations, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Maori Women's Welfare League, 1953

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Kaumātua and rūnanga: Maahunui Māori Council

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Te Whānau o Waipareira

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

RELIGION AND SPIRITUAL GROUPS

Religion and spiritual as defined by the Oxford Learner's Dictionary:

Religion — the belief in the existence of a god or gods, and the activities that are connected with the worship of them, or in the teachings of a spiritual leader.

Spiritual — connected with the human spirit, rather than the body or physical things.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, belonging to a religion and being spiritual can have a positive effect on wellbeing.

Wellbeing benefits of religion include:

- it gives people something to believe in

- it connects people with similar beliefs

- it provides structure, regularity and guidelines to live by

- it has life lessons for challenging situations.

Wellbeing benefits of Spirituality include:

- Helps individuals to connect with what they believe in or what is good for them

- Incorporates healthy practices

- Encourages introspection and meditation

- People find a meaningful connection to life and the world around.

Professor David Cresswell on mindfulness

Radio New Zealand

Church offering

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Christian Endeavour Group

Feilding Library

In the Pacific Islands, community life was built around the family, the church and the village. In New Zealand, churches acted like villages. The minister was the most powerful and respected person – a role similar to the village chief.

Churches became the centre of social life for many Pacific families. As well as religious worship, churches provide health and education services, and sport, music and social activities.

Source: Pacific churches in New Zealand, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Tahupōtiki Wiremu Rātana came to prominence as a powerful Māori spiritual leader and faith healer. He founded a religious movement and headed a pan-tribal unity movement campaigning for social justice and equality based on the Treaty of Waitangi.

Source: Founding the Rātana Church — Rātana Church — Te Haahi Rātana, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Pounamu - Tahupōtiki Wiremu Rātana

NZ On Screen

Ringatu Church meeting, Wainui near Ohope Beach

Alexander Turnbull Library

Church unity: Protestant churches' agreement

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

HOAMAHI — COLLEAGUES

The Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand recommends wellbeing as one of the most valuable business assets. Organisations that prioritise wellbeing have:

- better engagement

- reduced absenteeism

- higher productivity

- improved wellbeing

- greater morale

- job satisfaction

- better teamwork.

Workplace mental health package launched

Radio New Zealand

Happy staff at Hurley Bendon, Papatoetoe, 1964

Auckland Libraries

Communuication| Telecoms group at work

Antarctica New Zealand

TEAMS

There is lots of evidence to prove that sport has huge social and wellbeing benefits for children besides developing their body and mind. This is because children benefit from belonging to a team and engaging with other children.

An article from Healthdirect Australia advocates that sport has developmental, emotional and social benefits for children including:

- Children learn how to lose a game and bounce back from disappointment

- They learn that patience and practice help improve physical skills

- Regular sport increases overall emotional wellbeing

- Support from the team and coach help with self-esteem and achievement

- Sport teaches children to cooperate and communicate with other children

- Children follow the rules of the game and learn about discipline and teamwork.

For most New Zealand children sport has contributed to their sense of self and how others view them. Since colonial times, to be good at sport has been a way to increase one’s self-esteem and earn the respect of both peers and teachers. To become a member of the first XI (cricket) or first XV (rugby) or the ‘A’ (netball) team at secondary school was a childhood aspiration of many. For children who struggled academically, sport was one way to prove their worth.

Source: Identity and ethos — Children and sport, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Sports team with fire engine

Waimate Museum and Archives

Marching girls at Carlaw Park

Auckland Libraries

STRENGTHENING TAHA WHĀNAU

Good relationships with whānua, friends, groups and hoamihi ( work colleagues) are fundamental to social wellbeing. The Mental Health Foundation has some great ideas to strengthen taha whānau:

- Is there someone in your whānau you haven’t seen or talked to for a while? Take the time to reconnect. It could be kanohi ki te kanohi/face to face, or even through text or Facebook messenger.

- Start a social sports team – invite people from different areas of your life to join.

- Get to know your neighbours – invite people in the neighbourhood around for a cup of tea or go over and introduce yourself.

- Offer your time to help a friend, hoamahi/colleague or whānau member in need – it could be doing a working bee at their home, looking after their tamariki while they go to an appointment, picking up some basic groceries or taking the rubbish bins out for your neighbour!

- Write cards to people in your life who have made an impact on you – let them know why you appreciate them, just because you can!

Here are some other ways to strengthen social wellbeing:

SOCIAL SUPPORT

The Ministry of Social Development (MSD) defines social support as:

Social support refers to the support from people in a person’s social network that is either provided or perceived to be readily available in times of need.

According to MSD, social support can be divided into:

- Emotional support — This refers to caring, sympathy and understanding that one receives from someone close or a support group.

- Instrumental support — Here the focus is on providing financial assistance, or help with child care or care for the elderly or disabled.

- Informational support — This is about the direction to information sources that can assist with housing, finding employment, medical and financial advice.

Māori social-services team

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Auckland Women's Health Centre

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Caring for family

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

In New Zealand, people in need receive help from a number of sources, including family assistance, informal community aid, and through the more formal mechanisms of the state and voluntary organisations.

Source: Voluntary welfare organisations – overview — Voluntary welfare organisations, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Wellington Housing Trust

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Seventh-day Adventist Church social services

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Barnardos parent helpline

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

SENSE OF BELONGING

A sense of belonging is the feeling of being connected to and valued by other people. Whether it is sourced from family, friends, co-workers, club members, or a church community, people have an inherent desire to belong and be part of something greater than themselves.

Having a sense of belonging is a protective factor that strengthens people’s resilience. In contrast, feelings of loneliness are a risk factor and are argued to indicate a deficit in one’s sense of belonging.

Ministry of Social Development (MSD)

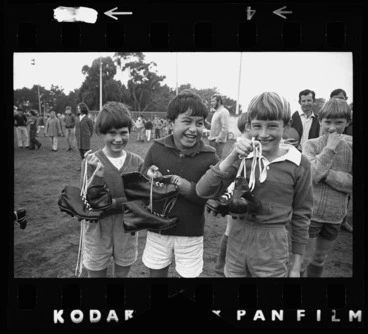

Children holding rugby boots

Christchurch City Libraries

Rowe Family, family portrait

Alexander Turnbull Library

Community groups: Auckland students' association

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

TĀ MOKO

From the 1970s Māori gang members wore moko as part of their gang insignia. From the 1980s the Māori renaissance encouraged tā moko as a way to express Māori or tribal identity.

Source: Tā moko — Māori tattooing, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

McLean's tāmoko honours ancestors

Radio New Zealand

Moko

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Tā Moko

NZ On Screen

EMPATHY

The magazine Psychology Today encourages us to practise empathy for those around us, but also for our own wellbeing because empathy:

- connects us to others

- lowers stress

- helps us communicate better

- helps us treat others better

- creates healthier communities

- is a foundation for moral behaviour.

2011 Ngati Moki Trophy Award Ceremony 1

Lincoln University

Teaching empathy

Radio New Zealand

The Empathy Gap and Me | E-Tangata

E-Tangata

STAND AGAINST BULLYING

Bullying is something that can happen to anyone, at any age and anywhere (in school, at work, online, at home etc), and in lots of different ways. Bullying-Free NZ has advice on how to support someone who is being bullied.

- Encourage a discussion about bullying.

- Stay calm and positive.

- Show them you believe their story.

- Assure them that they are not at fault for the bullying.

- Let them know that bullying is not okay.

- Help them to find a solution.

NZ schools have high rates of bullying, study finds

Radio New Zealand

Bullying

DigitalNZ

QUICK FACTS

- The lockdown in New Zealand due to COVID -19 had an impact on how people socially interacted with each other through their lives, work and play.

- ‘Social distancing’ is one of the measures used to reduce the spread of COVID-19. .

- Pink Shirt Day began in Canada in 2007 when two students took a stand against a peer being bullied for wearing a pink shirt. In New Zealand, Pink Shirt Day aims to make children and people feel safe and respected in schools, workspaces and communities.

- In Māori culture, whānau translates as ‘family.’, This includes physical, emotional and spiritual dimensions based on whakapapa (ancestry).

- 9 August was declared as the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples by the United Nations. This day is observed to protect the rights of the world’s indigenous community.

- DNA stands for deoxyribonucleic acid. It is the material that carries all the information about how a living thing will look and function. The genes in DNA pass on physical traits from generation to generation.

- The Freemason society has its origins in medieval lodges of British stonemasons and builders of cathedrals and castles.

- Tāne the god of the forest created the first woman Hineahuone from the soil and made her his wife. The human race is a result of their union. It is for this reason that Māori beliven that all living things are linked through whakapapa (ancestry).

- Pew Research Centre shows that Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism are four of the largest religious groups of the world.

- Group sports are a great way for children to learn to work together as a team while contributing to their overall wellbeing.

- The Weet-Bix TRYatholon for kids between 7 to 15 has become very popular. Kids are able to participate as an individual or as a part of a team.

- Participation is the main objective for this triathlon, and everyone who does is rewarded with a medal, certificate, t-shirt, kit bag and swim cap.

Social basketball game

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

GLOSSARY

Definitions below have been taken from the Oxford Learner's Dictionary.

ancestor— a person in your family who lived a long time ago.

cornerstone— a stone at the corner of the base of a building, often laid in a special ceremony.

deficit— the amount by which money spent or owed is greater than money earned in a particular period of time.

inherent — that is a basic or permanent part of somebody/something and that cannot be removed.

insignia— the symbol, badge or sign that shows somebody’s rank or that they are a member of a group or an organization.

interrelated— closely connected and affecting each other.

interdependent— that depend on each other; consisting of parts that depend on each other.

intersperse — to put something in something else or among or between other things.

introspection — the careful examination of your own thoughts, feelings and reasons for behaving in a particular way.

mechanism— a method or a system for achieving something.

renaissance — a situation when there is new interest in a particular subject, form of art, etc. after a period when it was not very popular.

resilience— the ability of people or things to recover quickly after something unpleasant, such as shock, injury, etc.

surrogate mother— a woman who gives birth to a baby for another person or couple, usually because they are unable to have babies themselves.

Wellington Golf Club Social [P1-6318-8708]

Upper Hutt City Library

SUPPORTING RESOURCES

GENERAL WEBSITES

Benefits of social wellness — the importance of social wellness and how to grow your social network.

EPIC — Find more information on this topic on EPIC. Databases recommended: Helth and Wellness (Gale). School login maybe required.

Health and wellbeing (hauora) — This page from Many Answers will guide you to reviewed websites and databases on health.

Importance of social wellness — for quality of life and some ways to achieve social wellness and build social networks for yourself.

Fly me up School Journal Nov: 2018 — Join New Zealand artist Tiffany Singh who works with communities to draw attention to social issues.

The Measurement of social connectedness and its relationship to wellbeing — a 2018 paper by Ministry of Social Development (MSD) intended to explore how social connectedness affects resilience and wellbeing for New Zealanders.

Ministry of Social Development — New Zealand government organisation that helps build strong individuals, families and communities.

Pacific health models — The Fonua Model and the Fonofale models which include a holistic view of good health for counties in the Pacific Islands.

Schools with good wellbeing practices — expertise on wellbeing in schools from the Education Review Office (ERO).

Social connectivity — as an essential part of social wellness.

Social wellness — signs of social wellness and exploring social wellness through communication and relationships.

Wellness wheel — an 8-dimension tool from the University of Hampshire for self-exploration to survey choices or situations that impact overall wellness.

FAMILIES

Good family relationships — why they are important and how to build them.

Healthy families NZ — a large scale initiative by the Ministry of Health that brings community leadership together in a united effort for better health.

TRIBAL ORGANISATIONS

Classic Māori society — Māori social hierarchy, their roles and significance.

The health benefits of finding your tribe — the power of the clan and the impact of change.

Healthy tribes — Centres for Disease Control and Prevention works with American Indians to strengthen connections to culture and traditional lifeways that improve health and wellness.

Traditional Māori society — Māori social organisation, the spiritual world and land (whenua).

WHAKAPAPA (GENEALOGY)

Family history is important for your health — knowing your family history is one of steps towards wellbeing.

SCHOOL

Creating a belonging place — Owairaka District school use adults from the community to support relevant, connected, future-oriented learning for students.

The importance of social connection in schools — for learning, and for mental and physical health and wellbeing.

Making a difference to student wellbeing — aims to provide schools with ways to enhance students’ wellbeing and decrease aggressive and bullying behaviours.

Social and business enterprises boost wellbeing — Students from St John’s College in Hastings receive awards and learning from being involved in the college’s social enterprise programme promoting wellbeing in their school and community.

COMMUNITY GROUPS

Everyone Included: Social Impact of COVID-19 — United Nations on the impact of COVID-19 on the elderly, youth, sport, indigenous people and people with disabilities.

Opportunities for social connection — examines the importance of social inclusion and participation and social relationships, networks and cohesion.

What is community wellbeing? — The importance of connectedness, liveability and equity to community wellbeing.

RELIGIONS AND SPIRITUAL GROUPS

Culture, spirituality, religion and health: looking at the big picture — their connection and how this can affect health.

Why work with religious communities — UNICEF lists the benefits of belonging to religious groups.

HOAMAHI (COLLEAGUES)

Five ways to wellbeing at work — practical toolkit of information, resources and know-how to support teams in organisations.

Wellbeing at work — five steps to a happy life on the job.

TEAMS

Influencing positive social change through sport — a podcast about the CEO of the New Zealand Football Foundation who wants to use sport to help build social cohesion.

Mental health benefits of playing a team sport — such as social aspect, de-stressor, resilience and more that help mental and physical wellbeing.

The social and academic benefits of team sports — soft skills fostered through team sports to build positive social relationships.

The value of sport — This report presents the findings of research commissioned by Sport NZ to understand the value of sport and active recreation in New Zealand.

Urbanesia dance workshop at Pacifica Arts Centre.

Auckland Libraries

A GALLERY OF IMAGES REFLECTING THE DIVERSE RANGE OF CULTURES PEOPLE BELONG TO IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND

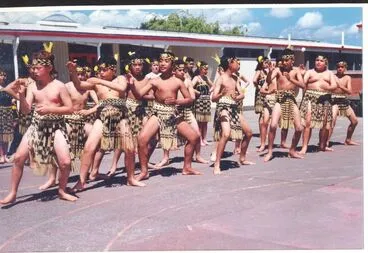

Taitoko Cultural Group performing, with boys at the front

Kete Horowhenua

Filipino Cultural Youth Group dancing Tinikling (Bamboo Dance)

Christchurch City Libraries

World on Your Plate: Cook Islands

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

Fijian meke dance, ASB Polyfest.

Auckland Libraries

Culture Galore

Christchurch City Libraries

7.10.78. Triangle Road, Massey, west Auckland. Tattooing Tom Ah Fook, Arona and Leo Maselino (solo). Tufuga tatatau: Su'a Sulu'ape Paulo II

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

CAR NZ male dance group members beating gongs

Christchurch City Libraries

Manawatū Russian Dance Group

Palmerston North City Library

Church group dancing

The University of Auckland Library

Patten, Group

Puke Ariki

Groups doing Bollywood dancing.

Auckland Libraries

Dancers, Niue

Auckland Libraries

Tongan dance performance, ASB Polyfest, 2016.

Auckland Libraries

This story was curated and compiled by Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, August 2020.