Battle of Waikato newspapers on eve of land wars

A DigitalNZ Story by Zokoroa

A war of words between two Māori language newspapers in a battle between Kīngitanga and the Government that preceded the Waikato wars of the 1860s.

Newspapers, Printing, Press, Media, NZ Land Wars, Māori, Tainui, Waikato, Maniapoto, Hochstetter, Waikato wars, Ngāruawāhia, Te Awamutu, Te Tuhi, Gorst, Tamihana, Kīngitanga, King movement, Māori King, Austria

On the eve of the New Zealand Land Wars, a media war had ensued between two rival Waikato newspapers written in te reo MāorI. Te Hokioi e Rere Atu Na was set up in Ngāruawāhia in 1862 to provide news of the Kīngitanga movement to Māori and further afield. Te Pihoihoi Mokemoke i Runga i te Tuanui was established at Te Awamutu in February 1863 by the Government. This story backgrounds the arrival of the printing press in Ngāruawāhia after two Māori men learnt the printing trade in Austria and were gifted the press by Emperor Franz Joseph; and the escalation of events leading to the subsequent war of words.

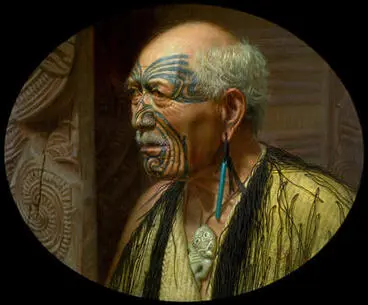

The pro-Kīngitanga newspaper "Te Hokioi" was edited by Patara Te Tuhi.

Patara Te Tuhi

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

The pro-Government newspaper "Te Pihoihoi" was edited by John Gorst.

Squires, W, fl 1870 (Photographer) : John Eldon Gorst, Cambridge, England

Alexander Turnbull Library

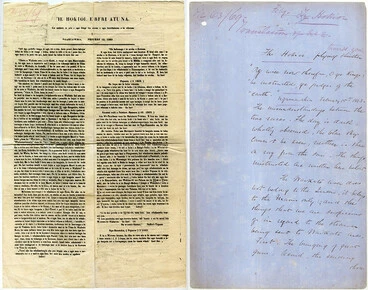

Copies of the newspapers written in te reo Māori and English translations are held by Archives New Zealand.

Te Hokioi and English translation, 1863

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Chapter 1: Māori LEARNING PRINTING IN vienna, 1859-1860

In September 1859, two Waikato Māori arrived in Austria and stayed for nine months learning the art of printing at the State Printing House in Vienna - Wiremu Toetoe Tumohe of Rangiaowhia and Te Hemara Te Rerehau Paraone of Ngāti Maniapoto. When asked what they would like as a parting gift from Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, they requested a printing press and type.

Two Waikato Māori learnt the art of printing at the State Printing House in Vienna for 9 months from Sept 1859.

Tribes of Tainui

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Toetoe and Paraone kept a journal of their experiences written in te reo Māori.

Notes on trip to Vienna by Wiremu Toetoe and Te Hemara Rerehau

Alexander Turnbull Library

Their journal was reproduced, including with English translations, in Te Ao Ho in 1958.

AUSTRIA AND THE MAORI PEOPLE; DIARY OF WIREMU TOETOE TUMOHE AND TE HEMARA REREHAU PARAONE - (Te Ao Hou - No. 24 October 1958)

Alexander Turnbull Library

What were the CONNECTIONS BETWEEN NZ AND AUSTRIA?

(A) Austrian scientific expedition arrives in NZ, Dec 1858

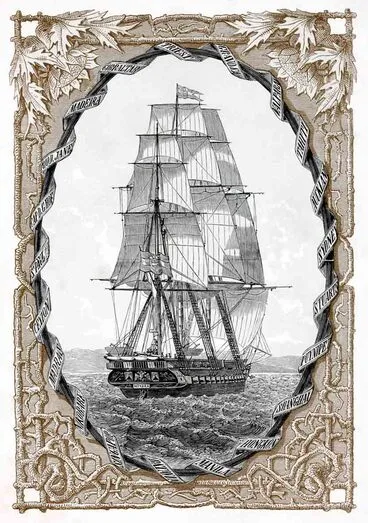

Archduke Maximilian, brother of the Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria and head of the Imperial Navy, authorised a scientific expedition to circumnavigate the globe. The frigate Novara left Trieste on 30 April 1857 under the command of Captain Bernhard von Wüllerstorf-Urbair. On board was a contingent from the Austrian Academy of Sciences, including geographer Dr Ferdinand Hochstetter, botanists Eduard Schwarz and Anton Jellinek, eoologist Georg Ritter von Frauenfield, and ethnographer Karl von Scherzer who had originally trained as a printer in Vienna. After sailing to Rio de Janeiro, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Hong Kong and Sydney, the Novara arrived in Auckland on 22 December 1858 and stayed until 8 January 1859.

Austria's Imperial Navy circumnavigated the globe on a scientific expedition from 1857-59.

The frigate Novara

Auckland Libraries

Contingent from the Austrian Academy of Sciences arrived in Auckland on 22 Dec 1858 and stayed until 8 Jan 1859.

Die Erdumsegeleng der Novara: Die Kommandirenden, Beamten und Gelehrten der Expedition

Auckland Libraries

Dr von Hochstetter's party visited the Waikato when surveying NZ.

Ferdinand Hochstetter, 1859

Auckland Libraries

(B) Hochstetter's party meets local Māori

Hochstetter and his party journeyed throughout the Auckland and Waikato districts and surveyed the Drury coalfields along the Waikato River. They recorded in their journals that they had experienced a warm reception from local Māori. (See Scherzer's account: Narrative of the Circumnavigation... by the Austrian Frigate, Novara [Ch. XIX, p. 174-6, 1863.]

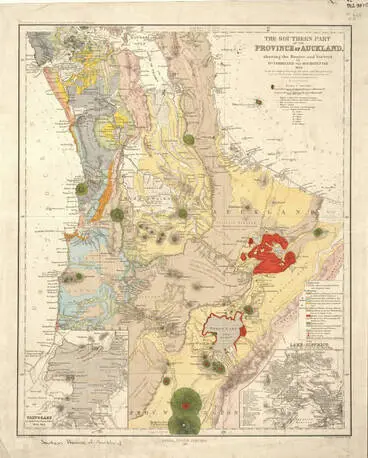

Auckland and Waikato areas surveyed by Hochstetter, 1859.

The southern part of the Province of Auckland showing the routes and surveys by Ferdinand von Hochstetter, 1859 from the original drawings, sketche...

Auckland Libraries

The Drury Hotel was the party's headquarters when surveying the Drury coalfields.

Bruno L. Hamel, The hotel at Drury, 1859.

Auckland Libraries

Hospitality was extended by local Māori.

Reception of the Government Scientific Exploring Expedition, Waipa

Alexander Turnbull Library

(C) Replacement crew required for Novarra, Jan 1859

The Novara's departure from Auckland in early January 1859 was delayed for several days due to gales. Bishop Kean Baptiste Francois Pompallier. his Vicar-General and several Māori chiefs visited on board to renew their hospitality. The ship's Captain enquired whether indigenous New Zealanders would like to join its crew. Two of the five South Africans that had signed up as sailors in Cape Town had deserted in Auckland. (They had been taken on board from a Cape Town prison with the permission of the governor of the Cape Colony, Sir George Grey who had left NZ in 1853 after being Governor since 1845.) Furthermore, Dr. Scherzer had written in his journal: "Since the first day of our arrival, I gave the order to have some nice tattooed aboriginals who are capable and willing to accompany us as seamen on the Novara" with the intent of continuing his ethnographic research.

When Novara's departure was delayed, Bishop Pomapallier and Māori chiefs socialised on board.

THE FRIGATE "NOVARA." (Daily Southern Cross, 07 January 1859)

National Library of New Zealand

Captain enquired whether indigenous New Zealanders would like to join the crew, which Dr. Scherzer noted in his journal.

Narrative of the Circumnavigation of the Globe

Auckland Libraries

(D) Toetoe and Paraone volunteered

The ship's Captain obtained the consent of Governor Thomas Gore Browne (who had replaced George Grey in 1853) that "four Maories and a half-blood " could join the expedition. When it was time to sail, Dr. Scherzer wrote in his journal, "At first four Maories and a half-blood had resolved on making the voyage, but when the time for embarkation came, only two adhered to their determination, Wiremu Toe-toe Tumohe, and Te Hemara Rerehau Paraone."

Consent of Governor Browne given for Māori men to join the expedition.

Col. Gore Browne. Governor 1855-1861

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

- Wiremu Toetoe Tumohe

Toetoe (aged about 32 years) was the Waikato district's Postmaster and chief of the two small Waikato iwi of the Ngāti Apakura and Ngāti Wakohike. He was born in 1826 and lived in Rangiaowhia near Te Awamutu. He had been baptised when about fifteen by an English missionary who had also taught him reading and writing. He was married at aged 20 to the daughter of an Englishman and Māori woman and had a son. In his twenty-sixth year he entered the service of the Colonial Government as a letter carrier delivering mail from Auckland to Taupō, and two years later was promoted to Postmaster. He was supportive of the Government building roads. (See photo, video and article in www.stuff.co.nz)

Wiremu Toetoe was contracted to carry the Government's mail from Auckland to Taupō; then became Postmaster.

THE OVERLAND POSTAL ROUTE. (Hawke's Bay Herald, 16 January 1858)

National Library of New Zealand

- Te Hemara Te Rerehau Paraone

Paraone (aged 20 years), also known as Hemara Rerehau Te Whanonga, was related to Toetoe. He had also been baptised and from his twelfth to his eighteenth year, attended a school founded by English missionaries in Ngāti Apakura, where he learned to write Māori, some English, arithmetic, geography, and history. He was described as being “young, intelligent, soft, and very communicative” (Gorst, 1862).

An account of the expedition's visit to the Auckland province and Paraone and Toetoe setting sail on the Novara.

Auckland section of Narrative of the Circumnavigation of the Globe

Auckland Libraries

(E) On board the Novara for Austria, Jan 1859

The Novara departed for Austria on 8 January 1859 with Toetoe and Paraone who had been signed on as sailors. After the frigate left the wharf and was gathering speed, Scherzer wrote in his journal that a boat appeared alongside "with several natives, and the Vicar-General, who wished to saddle us with some wonderfully tattooed Catholic Maories, anxious apparently that Protestant Maories should not alone be shipped." However, not wishing to delay their departure any longer, the Novarra carried on sailing. (See Karl Scherzer, Narrative of the circumnavigation... by the Austrian Frigate, Novara, 1863,, pp. 174-6.)

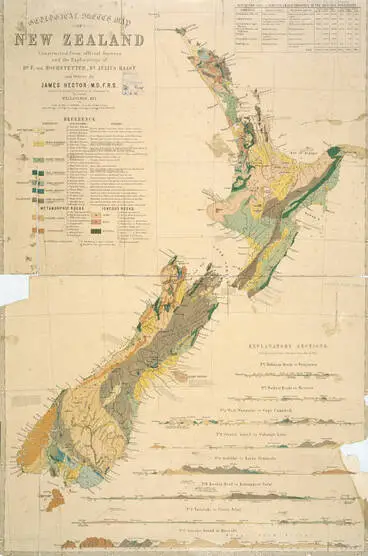

Meanwhile, Hochstetter remained behind in NZ at the request of the New Zealand authorities who were impressed with his initial report on the Drury coalfields. They asked him to conduct a full survey of NZ, offering to pay his expenses and return passage. Hochstetter stayed for nine months, spending most of his time near Auckland, but also visited Rotomahana's Pink and White terraces, Nelson and the Southern Alps. (See Victoria University: Novara visiting scholars)

When the Novara set sail, Hochstetter stayed on in NZ for nine months to complete a full survey.

Geological sketch map of New Zealand; constructed from official surveys and the explorations of Dr. F. von Hochstetter, Dr. Julius Haast and others

Auckland Libraries

Chapter 2: ARRIVAL IN VIENNA, SEPT 1859

(A) Dr. Scherzer arranged employment and accommodation

After arriving in Vienna in Sept 1859, it was arranged for Toetoe and Paraone to work at the State Printing House, where Scherzer had previously trained as a printer. How this came about is revealed in a letter written by the Director Alois Auer Ritter von Welsbach to the Sydney Printer J.N. Degotardi on 5 October 1859. He describes how Dr Scherzer "once arrived home, being uncertain what to do with the two Maoris, I offered to take them for the duration of their stay in Vienna into the State Printery as unpaid workers. I appointed them to the care of one of my foreman who treated them like members of his own family." (Source: Fletcher, John (1984). "From the Waikato to Vienna and Back: How two Maoris learned the printing trade". BSANZ Bulletin (vol 8, no.3). pp. 147-155).

Toetoe and Paraone arrived in Vienna in Sept 1859.

A VIENNA JOURNAL HE WHARE PEREHI O TE KINGI - (Te Ao Hou - No. 24 October 1958)

Alexander Turnbull Library

Director Auer's foreman was Herr Zimmerl: "An intelligent and linguistically gifted young man, a member of our Institute, has been commissioned to teach the two Islanders German and for his part to acquire with their help a knowledge of the New Zealand language, in order to be able in due course to employ this knowledge in the interests of our Institute." Furthermore, Auer wrote that the two Māori "could well become on their return to their mother country not unworthy missionaries amongst their fellow countrymen." As well as being trained by Zimmerl, Toetoe and Paraone also stayed with his family in Ottakring. (Source: John Fletcher, 1984).

Dr. Scherzer introduced Toetoe and Paraone to the Director of the State Printing House, Alois Auer.

Heid, Hermann, 1834-1891: Portrait of Karl von Scherzer

Alexander Turnbull Library

(B) Working at State Printing House, Sept 1859 - May 1860

Toetoe and Paraone stayed in Vienna for nine months until 26 May 1860 learning English and German and aspects of the printing trade from Zimmerl. In a later letter (15 June 1860), Director Auer summarised their progress: "They have learned how to composit and print, and how to carry out lithography and copper plate engraving".

A description of the State Printing House at Vienna, Austria had appeared in the Daily Southern Cross in 1851.

MISCELLANEA. The Imperial Printing Office at Vienna. (Daily Southern Cross, 30 September 1851)

National Library of New Zealand

(C) Journal kept of social and work experiences

During their time in Vienna, Toetoe and Paraone kept a journal of their experiences written in te reo Māori, which was reproduced in Te Ao Hou in 1958, with an English translation included. They were presented to many prominent European people, attended parties and learnt ballroom dancing. They also went sightseeing, including visiting various factories, government offices, museums, the railway, and the Imperial Zoological Gardens. According to the British Museum, while in Vienna Toetoe also had a son with the daughter of a Viennese officer, and the child was sent away to an orphanage in Hungary.

DIARY OF WIREMU TOETOE TUMOHE AND TE HEMARA REREHAU PARAONE - (Te Ao Hou - No. 24 October 1958)

Alexander Turnbull Library

Toetoe and Paraone also wrote letters to Sir George Grey, whose name they had seen in the Vienna newspaper. The first letter (19 Feb 1860) lauded Grey as having been the best Governor of New Zealand. (Grey had been Governor from 1943 to 1853, then became the Governor of the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa in late 1853.) Their second letter (8 May 1860) refers to the idea of unifying the two peoples, English and Māori, under one law and the Queen of England as 'mother' and authority, with Governor Browne and Pōtatau Te Wherowhero as her representatives in New Zealand.

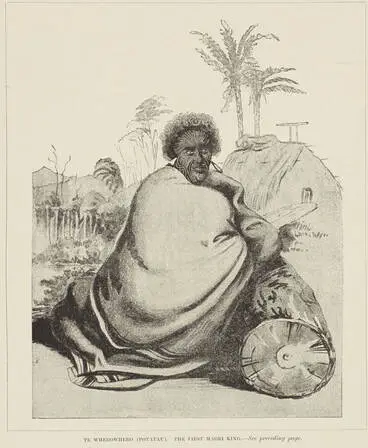

Pōtatau Te Wherowhero had been appointed the first Māori King in June 1858

Te Wherowhero (Potatau), the first Māori king

Auckland Libraries

(D) Reception with Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph

Toetoe and Parone received an invitation from Emperor Franz Joseph and Empress Elisabeth to attend a reception at the palace on 17 May 1860 prior to their departure from Austria. They were accompanied by Zimmerl who acted as interpreter. Beforehand, they had printed their speech, written in Māori and German (translated by Zimmerl), on the printing equipment. They gave out copies which the Emperor read and then invited Toetoe to deliver in Māori. Their address, which gave greetings to the Emperor and Empress and a salutation to 'The inhabitants of Vienna', was favourably received and printed in the Vienna newspaper. Copies can be read in Hochstetter's book about Neu-Seeland (1863) on pp. 528-530. (Source: John Fletcher, 1984)

In May 1860, Toetoe & Paraone met the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, accompanied by Zimmerl as their interpreter.

Albert, Josef 1825-1886: Emperor Franz Josef I

Alexander Turnbull Library

Their speech to the Emperor was published in the Vienna newspaper.

FOREIGN MEMORANDA. (Wellington Independent, 29 May 1860)

National Library of New Zealand

Hochstetter's book about New Zealand (1863) includes copies of Toetoe & Paraone's speeches to the Emperor.

Neu-Seeland von dr. Ferdinand von Hochstetter. Mit 2 karten, 6 farbenstahlstichen, 9 grossen holzschnitten und 89 in den text gedruckten holzschnitten

HathiTrust

(E) Printing press as parting gift from Emperor

The Emperor's brother Archduke Maximilian asked Toetoe and Parone what they would like as a parting gift and they requested a printing press and type, which was granted by the Emperor. The printing press, which was made of cast iron and stood five feet tall, was an Albion handpress which was manufactured in England by Hopkinson and Cope in the mid-1800s. It was shipped to Mangere where Pōtatau, the first Māori King, was residing since the late 1840s. The actual date of the arrival of the Emperor's gift is unknown. (see Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol 67, 1968)

FAREWELL TO VIENNA - (Te Ao Hou - No. 25 December 1958)

Alexander Turnbull Library

(F) Travels to Bavaria, Germany and England; then home, May-June 1860

After departing from Austria on 26 May 1860, Toetoe and Paraone journeyed onto Bavaria. They stayed with Hochstetter, who had returned from NZ in January, and accompanied them through Germany to England. When in England they were presented to Queen Victoria on 19 June. They had became aware of conflicts in the Taranaki and took the opportunity to declare their loyalty to the British Empire. Photos were taken of Toetoe and Paraone by portrait photographer Antoine Claudet, which are displayed in the British Museum. These portraits were presented by Dr Sasha Nolden at the Hochstetter Symposium at the University of Auckland in 2008 and later featured in various exhibitions at Auckland City Libraries and other institutions (see Te Awamutu Courier, 14 Jan 2010). Toetoe and Paraone left Southampton, England on 23 June 1860 on board the clipper ship Caduceus and arrived back at Auckland on 11 October.

Toetoe and Paraone stayed with Hochstetter who also accompanied them to England.

BARON HOCHSTETTER-THE NOVARA EXPEDITION. (Colonist, 10 July 1860)

National Library of New Zealand

Toetoe and Paraone left England in June 1860 and arrived back home on board the clipper ship Caduceus in Oct.

Untitled (Colonist, 24 August 1860)

National Library of New Zealand

Chapter 3: newspaper WANTED BY MĀori

(A) Earliest newspapers in te reo Māori were published by Government

The earliest newspapers that used the Māori language were published by the Government. The purpose was expressed in Te Karere o Niu Tireni (in various titles, 1842-63) as being to instruct Māori in the customs, laws and government of the Pākehā. The intent of The Maori Messenger – Ko te Karere Maori - The Star of the Year (1849–1860) was civilising Māori, of which an editor was Charles Oliver Bond Davis. In 1842, Davis had been appointed as a clerk and interpreter in the Government's Protectorate and Native Secretary's Office. When the Native Secretary's Department was created in 1846, he assisted in the Auckland courts with land purchases and native affairs. After leaving the Native Department in 1857, Davis published the newspapers Te Waka o te Iwi - The Canoe of the People (Oct-Nov 1857) and Te Whetu o te Tau (June - Sept 1858), to better inform the Māori people about settler and government intentions.

Earliest newspapers that used the Māori language were published by the Government.

The Maori Messenger – Te Karere Maori

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

(B) Fundraising for Māori newspaper (1857-60) supported by Charles Davis

When Māori expressed a wish to have their own newspaper to air their views, their idea was supported by Charles Davis. He had become acquainted with Māori chiefs in the Auckland and Waikato area through his Government roles and newspaper production activities, and attended several of the King movement meetings which culminated in the selection of the Māori King. Davis contacted Waata (Walter) Kukutai, Chief of Ngāti Tipa living at the Waikato Heads, to suggest collecting funds to purchase land in Auckland to erect stores for Māori to sell their produce and to set up a printing office for which he already had a printing press that could be used. He suggested a target figure of £1000, of which £500 would be sufficient for the printing office. (See Report of the Waikato Committee 1860, JHR, sections 542- 543.)

Charles Davis supported Māori wanting to establish their own newspaper.

Charles Davis

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Davis was involved in newspaper production and had a printing press they could use.

Te Waka o Te Iwi 1857: Volume 1, No. 1

University of Waikato

Waaka Kukutai took up Davis' suggestion of fundraising to purchase land to erect stores & a printing office in Auckland.

Walter Kukutai, chief of Lower Waikato

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

(C) Davis at Parliamentary hearing (1860): insufficient funds raised

Charles Davis' associations with Māori brought "official suspicion and displeasure" (Te Ara). He was directed to appear as one of the witnesses at the parliamentary hearings held by the Waikato Committee which met from 25 Sept to 21 October 1860. The purpose was to discuss civil government and the King movement which had been growing in momentum since 1857. Davis explained that he respected Māori people for their "very high sense of natural justice", but he was opposed to the nationalist tendencies of the King movement. He advocated more efficient Government administration and better information provided to Māori to allay anti-government feeling.

Davis was directed to appear before the parliamentary Waikato Commiitee which met from 25 Sept - 21 Oct 1860.

THE WAIKATO COMMITTEE. (Wellington Independent, 07 May 1861)

National Library of New Zealand

When questioned by the Waikato Committee as to whose idea it was to establish the new newspaper, Davis replied it had originated from Māori. He advised that insufficient funds had been gathered to purchase the land for the stores and printing office. He had not as yet used the press with the Māori people as "I have been fearful of publishing anything lest the government should be embarrassed, the Native mind being in so excited a state. They wished me to send them the printing press, that they might manage it themselves and publish their own opinions; but being fearful of their making a bad use of it, I wished to bind them to their original agreement, viz., that all publications should emanate from Auckland." See Report of the Waikato Committee 1860 (JHR, sections 542- 543). Coincidentally, at that time during the Committee hearings, the Emperor's press arrived in Auckland and was delivered to the Māori King.

Chapter 4: Emperor's PRESS & Te Hokioi Newspaper

(A) Printing press set up in Mangere, Sept 1861

The printing press from Emperor Franz Joseph was set up in Mangere where King Pōtatau Te Wherowhero had resided. At Governor George Grey's request, Pōtatau (Ngāti Mahuta) and some of his followers had moved to Mangere and in 1849 he signed an agreement to provide military protection for the city of Auckland (See Te Ara). Later in 1859, Pōtatau was appointed as the first Māori King and returned to live in Ngāruawāhia in May 1860 where he passed away on 25 June. He was succeeded by his son Tāwhiao who was appointed King on 5 July 1860 at Ngāruawāhia. (AJHR, 1860, E-1C, p. 34; F-3, p. 101, cited in Gorst's, The Maori King)

Printing press from the Emperor was set up in Mangere (Sept 1861) where Pōtatau had resided since late 1840s - May 1860.

Te Hokioi printing press

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

The very first documents printed were single-paged letters by Tamati Ngapora (2 Sept 1861) and Te Hira Te Kawau (21 Sept 1861) notifying people of the deaths of Kahukoti and Wi Koihoho. They both bear the imprint, ‘Mangere. I taia tenei ki te Hokioi o Nui Tireni’ (This was printed at Mangere at Te Hokioi of New Zealand). The typesetter was Honana Maioha of Ngāti Mahuta whose father was a cousin of King Pōtatau. According to James Cowan (Auckland Star, 15 April, 1922, p.208), the art of composing type was taught to Maioha and other young Māori by Charles Davis' nephew who had learnt the trade in the New-Zealander newspaper office at Auckland. Any involvement by Toetoe and Paraone in using the printing press on their return from Austria is not known.

(B) Printing press moves to Ngāruawahia

The printing press was then shifted to Ngāruawāhia where Tāwhiao, who had succeeded his father as King, lived. The printing equipment was probably located at the Hopuhopu Mission Station (see Te Awamutu Museum).

Printing press then shifted to Ngāruawāhia where Tāwhiao, who had succeeded his father as King in July 1860, lived.

Ngāruawāhia, 1861

Auckland Libraries

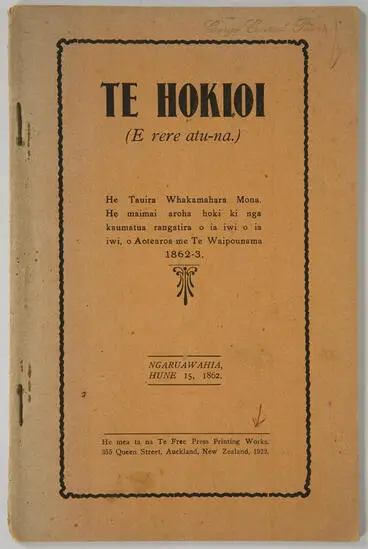

(C) Te Hokioi newspaper published, 1862-63

The four page newspaper Te Hokioi e Rere Atu Na was published on the printing press from 15 June 1862 - 21 May 1863. Te Hokioi was a spirit bird of ancient times. It was never seen but its cry was known as an omen of war or disaster. The newspaper's name has been variously translated as The Soaring War Bird and The War-Bird of New Zealand in Flight to You. The press bore the arms of the Austrian Royal House. "The imprint at the end of June 15, 1862, reads: "Te perehi, aroha noa o te Kingi O Atiria" [The press given with affection by the King of Austria] (See Greenstone.org).

Te Hōkioi

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

(D) Editor: Patara Te Tuhi

The newspaper's editor and principal writer was Patara Te Tuhi (Ngāti Mahuta). He was assisted by his younger brother, Hōnana Maioha, and youths who set the type and worked the hand press. Te Tuhi's father Paratene Te Maioha was a cousin of Pōtatau. Te Tuhi became a secretary and adviser of Tāwhiao who succeeded his father as King in July 1860. During his youth, Te Tuhi had attended mission schools. His original name was Te Taieti and he took William Butler (Wiremu Patara) as his baptismal name, to which was added Te Tuhi in recognition of his writing skills. (See Te Ara)

Patara Te Tuhi - editor & principal writer

Te Tuhi's father was a cousin of first Māori King & Te Tuhi was secretary & adviser of Tāwhiao who succeeded his father.

Alexander Turnbull Library

(E) Newspaper was pro-Kīngitanga

Te Hokioi was to be the voice of King Tāwhiao and to provide news of the King movement to Māori and further afield. The King movement, or Kīngitanga, was formed to create a symbol of unity across the many different iwi and hapū under a Māori king and to help protect Māori land ownership. As stated in the first issue, "The value of this press is that it will convey our thoughts to all the inhabitants of the world, because word from the beginning has always been straightforward — " religion, love, and law"."

Documentary recounts the birth of the King Movement and the new Governor's determination to reassert British authority.

The New Zealand Wars - Episode 2, Kings and Empires

NZ On Screen

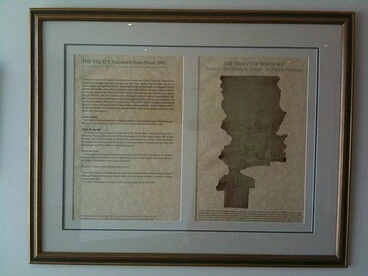

(F) Editor's interpretation of Treaty of Waitangi to limit sovereignity

Te Tuhi argued for an interpretation of the Treaty of Waitangi that would limit the sovereignty of the colonial government over Māori. He argued, for instance, that the presence of a government steamer on the Waikato River, without the permission of the Māori owners of the river, violated the Treaty: "Successive Governors have declared to us that the Queen, by the Treaty of Waitangi, promised us the full chiefship of such of our lands, rivers, fisheries, &c. as we might wish to retain. Now Waikato is one of the rivers which we wish to retain under our own chiefship. How is it, then, that we are told a steamer is to be sent into this river, though we have not given our consent? Is this the way in which the Treaty of Waitangi is observed by your side? Pakeha friends, why do you act thus wrongfully, or trample under your feet the words of your Queen?"

Treaty of Waitangi

Aotearoa People's Network Kaharoa

(G) First issue of Te Hokioi newspaper, 15 June 1862

The first editorial by Patara Te Tuhi noted, "Kote perehi kua tae mai ki Ngaruawahia ka puta i a ia nga Nuipepa...ko te pai o enei perehi hei kawe i a tatou whakaro, ki nga iwi o te Ao; no te mea hoki e takoto ana nga kupu o te timatanga ko te whakapono, ko te aroha; ko te ture" [The press has arrived at Ngaruawahia, and newspapers are being produced from it...this press is ideal for carrying our thoughts abroad for it was founded on the words: faith, love and law]. (See Greenstone.org).

(H) Newspaper's content included:

- Letters from Māori people throughout Aotearoa supporting the Māori King's stand against selling land

- Reports of meetings held to discuss the King Movement

- Letters to Governor Grey from Pōtatau Te Wherowhero

- An account of collecting money at Puketapapa, Manukau on Christmas Day to build a church at Ngāruawāhia

- An appeal by Governor Grey to King Tāwhiao for peace

- Proclamations by the Māori King, such as the fee to be paid for crossing the Waikato River at Taupiri

- Letters complaining about the difficulty in purchasTe Hokioi in Wellington

- Overseas news

- Waiata.

Source: GREENSTONE.ORG

PATARA, THE SCRIBE. (Star, 18 February 1902)

National Library of New Zealand

(I) Printed twice a month & distributed by rūnanga

The newspaper was to have two issues each month, cost 3 pence and be distributed to a contact person in each rūnanga (tribal council). As was reported by the Nelson Examiner and other newspapers, "It will be published twice every month, on the Ist and on the 15th. The price of a single paper is 3d; per year, 6s. Take notice, it is for each runanga to decide who shall be the person in each district with whom the paper shall be left, like this for Eangiaohia, with Taati ; for Tamahere, with Kiln ; for Maungatartari, with Tioriori. This is the plan by which the papers are to be distributed to all parties : there shall be one person that shall have them and look after them, each person must fetch them from him without delay."

Te Hokioi 1862-1863: No. 1

University of Waikato

Te Hokioi 1862-1863: No. 2

University of Waikato

Te Hokioi 1862-1863: No. 3

University of Waikato

(J) Extracts were published by other newspapers

(K) Issues of Te Hokioi were translated by newspapers

THE FOLLOWING IS A TOLERABLY CLOSE TRANSLATION OF THE GAZETTE OF KING POTATAU. (Taranaki Herald, 27 December 1862)

National Library of New Zealand

LATEST OFFICIAL NEWS FROM NGARUAWAHIA. (Daily Southern Cross, 09 January 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

THE HOKIOI. (Daily Southern Cross, 13 June 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

Translation ] THE HOKIOI. IS FLYING. (Daily Southern Cross, 03 July 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

LETTERS FROM THE HEADQUARTERS AT NGARUAWAHIA. (Wellington Independent, 24 December 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

ChapTer 5: ESCALATION OF EVENTS LEADING TO WAR OF WORDS

A series of events took place creating tension in the Waikato. This led to Governor George Grey (who had replaced Browne in late 1860) establishing a newspaper in the Waikato to answer the arguments of the Hokioi. These events included the Kīngitanga movement, the Taranaki land dispute, the setting up of civil government, and the government's building of roads and barracks along the Waikato River.

(A) Beginnings of Kīngitanga: Te Rauparaha visits Queen Victoria, 1852

After the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the major issues for Māori were seen as, "the desire of the growing settler population for more land, and increasing social disorganisation as a result of European contact." (Source: Te Ara) In 1852 Tāmihana Te Rauparaha, the son of the Ngāti Toa chief, met Queen Victoria in England. When he returned home he sought to establish a monarchy for Māori, believing that Māori would be better off if iwi could unite - to bring an end to intertribal conflict, keep Māori land in Māori hands and provide a separate governing body for Māori. British unity under the Crown was perceived as a strength, and supporters of the Kīngitanga believed that if Māori could replicate this sense of unity they would have a better chance of withstanding the full impact of colonisation. Despite this argument, iwi such as Ngāpuhi, Te Arawa and Ngāti Porou did not join the Kīngitanga. Some opponents dismissed it as a Waikato movement that had little support in other parts of the country.

Origins of the Māori King Movement

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

STORY OF THE KING MOVEMENT. TOLD BY A MAORI CHIEF. (Timaru Herald, 01 March 1882)

National Library of New Zealand

(B) The search for a Māori king: 1852-58

Te Rauparaha’s cousin, Mātene Te Whiwhi (Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Toa), researched the ancestry of possible candidates for the kingship. Te Whiwhi then travelled around the North Island seeking to persuade suitable chiefs to put themselves forward. He was assisted by Wiremu Tamihana of Ngāti Haua who had been baptised a Christian. Tamihana hoped that a Māori kingship would provide effective order and laws, unlike the Pākehā government, which allowed Māori to kill each other and only involved itself when Pakeha were killed. (See Te Ara.)

Te Rauparaha’s cousin, Mātene Te Whiwhi, researched possible candidates who were then approached.

In search of a king - Māori King movement origins

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Candidates were approached by Te Whiwhi, with the assistance of Wiremu Tamihana.

THE WAIKATO MOVEMENT FOR A NATIVE KING. (Taranaki Herald, 27 June 1857)

National Library of New Zealand

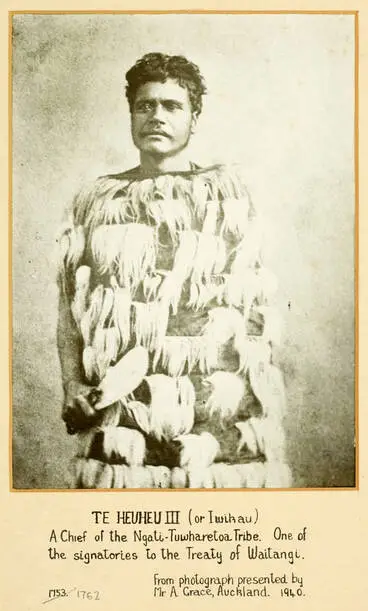

Chiefs approached by Te Whiwhi and Tamihana included Iwikau Te Heuheu Tūkino who suggested Pōtatau Te Wherowhero.

Iwikau Te Heuheu Tukino III

Auckland Libraries

Iwikau Te Heuheu Tūkino III of Ngāti Tūwharetoa turned Te Whiwhi down twice. In 1856, Te Heuheu held a meeting at Pukawa, Lake Taupō where he suggested offering the Māori kingship to Pōtatau Te Wherowhero of Ngāti Mahuta. Te Tuhi, then known as Taieti, was present as Pōtatau's representative. (See NZHistory and Te Ara.) Afterwards, Tamihana invited Waikato and Ngāti Maniapoto to a meeting held in May 1857 at Paetai, near Rangiriri, where they ratified the kingship offer to Pōtatau. After further discussion at a meeting at Ihumatao, on the Manukau Harbour, a large gathering at Ngāruawāhia in June 1858 agreed to Pōtatau becoming the first Māori King. (See Te Ara and Gorst's Maori King, pp.264-268.)

(C) Māori King chosen, 1858

At first the elderly Pōtatau was reluctant to accept the kingship role but was encouraged by Tamihana. He eventually agreed during a meeting held at Haurua in 1857, when it was suggested that on his passing that his son, Tāwhiao, could carry on the kingship, which might then become hereditary. During the large gathering at Ngāruawāhia in June 1858, where Pōtatau was declared the king, Tamihana provided a statement of laws, based on the laws of God. The King would exercise power over people and lands, over chiefs and councils of all the tribes; the tribes would continue to live on their own lands, and the King would protect them from aggression. (See Te Ara.)

Appendix — The Election of the Maori King - The Maori King

Victoria University of Wellington

Pōtatau was formally appointed the following year at a ceremony held in Ngāruawāhia on 2 May 1859. In his acceptance speech, Pōtatau stressed the spirit of unity symbolised by the kingship, likening his position to the ‘eye of the needle through which the white, black and red threads must pass’. He called on his people to ‘hold fast to love, to the law, and to faith in God’. (See Te Ara)

THE "NATIVE KING" MOVEMENT. KING POTATAU'S FIRST "RECEPTION." (Daily Southern Cross, 09 July 1858)

National Library of New Zealand

(D) Māori Kingship seen as a challenge to Queen Victoria

Many government officials chose to interpret the King movement as a direct challenge to British rule. However King Pōtatau and his supporters maintained that their movement was not intended as a challenge to Queen Victoria. This had been publicly demonstrated at the meeting held at Ngāruawāhia to formally appoint the King. Pōtatau was confirmed as holding the mana of kingship, in an alliance with Queen Victoria, with God over both; and he was annointed by Tamihana who placed a Bible over Pōtatau's head. (See Te Ara.) Pōtatau saw unity under the umbrella of the Kīngitanga as the most effective way to protect Māori land ownership and to help protect tribal structures and customs from the impact of Pākehā practices and beliefs. As Tamihana had been instrumental in supporting the establishment of a Māori king, he was subsequently given the title of 'Kingmaker' by Pākehā.

Many government officials saw Māori kingship as a challenge to British rule.

Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom

Alexander Turnbull Library

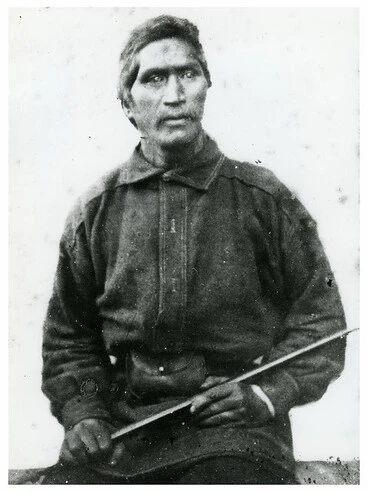

Wiremu Tamihana (Chief of Ngāti Hauā) annointed Pōtatau as Māori King and was regarded as "Kingmaker" by Pākehā.

Wiremu Tāmihana Tarapīpipi Te Waharoa of Ngāti Hauā, 1863

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

(E) King Pōtatau established territorial boundary

A number of chiefs placed their tribal lands under the protection of King Pōtatau as a guarantee against sale. Within their territory, the king's law, administered by his rūnanga (tribal council), would prevail. King Pōtatau established a boundary between the territory in which his authority held sway and that of the Governor: "Let Maungatautari [River] be our boundary. Do not encroach on this side. Likewise I am not to set a foot on that side." His aim was not to oppose the Crown but to provide authority in the lands placed under his mana (authority). Supporters believed it was possible for the mana of the two monarchs to be complementary. To Māori, the Kīngitanga was a development for Māori, not against Europeans. (See NZ History). However, in June 1857, Governor Browne wrote to London that "I apprehend no sort of danger from the present movement, but it is evident that the establishment of a separate nationality by the Maoris in any form or shape if persevered in would end sooner or later in collision."

King Pōtatau established the Maungatautari River as the boundary between his authority and the Governor.

Hamley, Joseph Osbertus, 1820-1911 :Maungatautari [March or April 1864]

Alexander Turnbull Library

(F) Civil Government & hearings before Waikato Committee, 1860

The New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 gave the vote to all adult males owning property of a certain value. This meant that communally held Māori land was not recognised. As not all Māori landowners had political voting rights, they set up their own unofficial rūnanga where chiefs and elders could hear disputes and administer their own people. The registrant magistrate in the Waikato, Francis Fenton, encouraged the government to pass legislation in 1858 to grant official status to rūnanga by setting up 'native districts' headed by the rūnanga. He believed this would make Māori more willing to sell their remaining lands and less likely to rebel against the government. However, little effort was made to implement these new laws and the King movement had been gaining in momentum since 1867.

The 1852 Act gave the vote to adult males owning property of a certain value, which excluded communally held Māori land.

Constitution Act 1852

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

As not all Māori landowners had political voting rights, they set up unofficial rūnanga (tribal councils).

PARLIAMENTARY PAPER. Report by Mr. Hanson Turton respecting the Runanga Maori. Continued. (Daily Southern Cross, 02 August 1862)

National Library of New Zealand

Fenton encouraged legislation passed in 1858 to grant official status to rūnanga by setting up 'native districts'.

41 Native Districts Regulation Act 1858

The University of Auckland Library

The Waikato Committee of the House of Representatives had been set up in 1860 to enquire into the actions taken by Fenton towards setting up civil government and the impact of the King movement. Various witnesses were directed to attend the hearings, including Charles Davis. See Report of the Waikato Committee 1860 (JHR, sections 542- 543).

Parliamentary hearings held by Waikato Committee (1860) on actions to set up civil government and impact of Kīngitanga.

THE WAIKATO COMMITTEE. (Lyttelton Times, 12 December 1860)

National Library of New Zealand

(G) Tāwhiao succeeds Pōtatau as Māori King, July 1860

Pōtatau returned to live in Ngāruawāhia in May 1860 where he passed away on 25 June. He was succeeded by his son Tāwhiao who was appointed King on 5 July 1860 at Ngāruawāhia. (See: Te Ara- Tāwhiao, Tūkāroto Matutaera Pōtatau Te Wherowhero)

(H) Waitara Land dispute in Taranaki, 1860-61

In 1859, Te Ātiawa chief Te Teira Mānuka offered to sell land at the mouth of the Waitara River in north Taranaki to the Crown, which Governor Browne accepted. However, Wiremu Kīngi, a more senior chief, denied that Teira had the right to sell the land, and his supporters obstructed surveyors. Martial law was declared on 22 February 1860 and Camp Waitara was established on the disputed land. War followed and a military truce was reached on 18 March 1861 with Wiremu Tāmihana (Ngāti Hauā iwi of the Tainui confederation) acting as mediator. Later, war broke out again in 1863. (See NZHistory)

Controversy over sale of land at Waitara sparked Taranaki war on 22 Feb 1860; truce was reached on 18 March 1861.

Military camp, Waitara, 1860

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

(I) Governor Browne's ultimatum to Waikato iwi, 1861

When fighting broke out between British troops and supporters of Wiremu Kīngi, the Kīngitanga was portrayed as being behind the Taranaki war. However, most Kīngitanga supporters in lower Waikato, including Tamihana, had opposed involvement. When Ngāti Maniapoto warriors joined the fighting, Governor Browne seized on this to accuse Waikato of violating the Treaty of Waitangi. Browne's "Declaration by the Governor to the Natives assembled at Ngaruawahia," was delivered during a rūnanga held in July 1861. He demanded that the Kīngitanga submit ‘without reserve’ to the British Queen.

Governor Browne's ultimatum to Waikato delivered at Ngāruawāhia, July 1861.

THE WAIKATO ULITIMATUM. (Hawke's Bay Herald, 22 June 1861)

National Library of New Zealand

(J) Tamihana's response to ultimatum

Tamihana (also known as William Thompson) wrote a lengthy response, indicating, with reference to Scripture and Māori metaphor, that the King movement was an organisation to control Māori people, and was not in conflict with the Queen's sovereignty - King and Queen could exist together, with God over both. (See NZHistory).

Response by Tamihana (also known as William Thompson) and others at the rūnanga.

THEIR REJECTION BY THE RUNANGA. (Wellington Independent, 09 July 1861)

National Library of New Zealand

(K) Governor Browne plans invasion of Waikato; then replaced by Grey, 1861

Governor Browne began planning an invasion of Waikato. However, his six-year appointment ended and he was reassigned to Tasmania before this could happen. Later in 1861 George Grey was reappointed for a second term as Governor of NZ and returned from Cape Town: "The hope was that through his mana and authority he could make peace." (NZHistory)

Build up to Waikato war by Governor Browne; then his 6 year appointment ended. in 1861.

Build-up to war

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Browne was replaced by Grey as Governor in late 1861.

Sir George Grey — (From a photograph about 1860)

Victoria University of Wellington

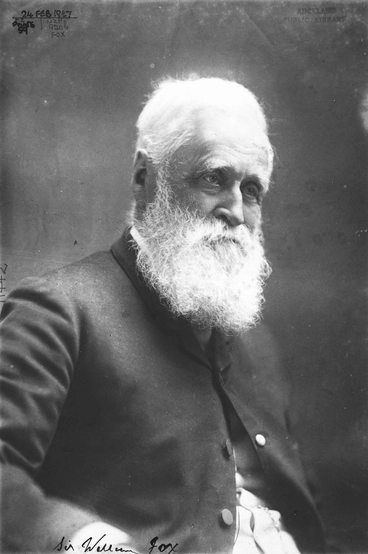

Premier Fox recommended Gorst for the position of Resident Magistrate for Waikato.

Sir WIlliam Fox

Auckland Libraries

(L) New system of local government introduced in 1861

In 1861, Governor Grey "introduced a system of ‘new institutions’ – local tribal councils. Known as rūnanga, these would have some administrative and judicial functions. The aim was to avoid a repetition of the Waitara disaster, encourage further land sales, and create common ground between settler and Māori which would help racial assimilation." (NZHistory) Grey's proposals were discussed at several meetings at which Tamihana mediated. Tamihana was not enthusiastic about Grey's proposals for native government, insisting that the rūnanga already established provided an appropriate system.

George Grey introduced a mew system of rūnanga in late 1861.

Governor Grey's rūnanga system

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Governor Grey's speech (12 Aug 1862) to General Assembly on state of NZ affairs on his return to the country.

GOVERNOR GREY'S SPEECH. (Colonist, 12 August 1862)

National Library of New Zealand

(M) Grey's appointment of Gorst creates tension in Waikato, 1862-63

> Gorst appointed as Registrant Magistrate, 1862:

In January 1862, Governor Grey. appointed John Eldon Gorst as Resident Magistrate for Waikato which was on the recommendation of the Premier, William Fox. Gorst had been born in Lancashire, England in 1835, studied law and maths, and taught at a local school. He arrived in NZ in May 1860 and settled in the Waikato with his wife and raised a family. Gorst taught at a mission school for Māori boys at Hopuhopu. In November 1861, he was sent by the Premier, William Fox, to inspect government-subsidised mission schools in the Waikato. (See Te Ara)

John Gorst had studied law & maths and taught at a school in England before arriving in NZ in 1860.

John Eldon Gorst

Alexander Turnbull Library

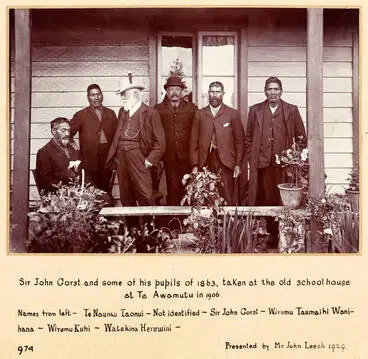

Gorst had taught at a mission school for Māori boys at Hopuhopu and was sent by Premier Fox to inspect mission schools.

Sir John Gorst and some of his pupils, 1906

Auckland Libraries

As Registrant Magistrate, Gorst resided at Reverend John Morgan's Otawhao Mission Station at Te Awamutu where he also took over the school. On 31 January 1862, Gorst received a rumour that three bands of Ngāti Maniapoto were planning to expel himself along with others: "one to drive away the Rev. Mr. Schuakenburg from Kawhia, a second to expel Mr. Reid from Waipa, and the third to removc Mr. Morgan and myself from Otawhao".

Resident Magistrate Gorst heard rumour that Ngāti Maniapoto planned to remove him & others from the Waikato (Jan 1862).

PARLIAMENTARY PAPER. UPPER WAJKATO MR. GORST'S REPORTS (Daily Southern Cross, 24 July 1862)

National Library of New Zealand

> Gorst appointed as Civil Commissioner of Upper Waikato, 1863:

Governor Grey then employed Gorst as Civil Commissioner of the Upper Waikato, which the Kingites considered their own land. Gorst was tasked with introducing the Government's new local government scheme based on cooperation with Māori rūnanga. However, he found that “The Maori from the first refused to consent to my exercising any kind of authority among them.” Even his friend Wiremu Tamihana objected to the admission into the Kingite district of a magistrate who received his authority from the Queen. (See James Cowan (1922), The old frontier, p.24)

Māori, including Grey's friend Tamihana, objected to a Civil Commissioner in the Kingite district.

Wiremu Tamihana Tarapipipi Te Waharoa with a double barreled shot-gun

Alexander Turnbull Library

James Cowan's book "The old frontier" includes a chapter on Gorst's time at Te Awamutu.

[untitled figure] - The Old Frontier : Te Awamutu, the story of the Waipa Valley : the missionary, the soldier, the pioneer farmer, early colonizat...

Victoria University of Wellington

(N) Concern over building of military road and barracks, 1862

The Waikato River was the main transport route from Auckland to the Waikato. In January 1862, work began on building the Great South Road to provide an additional route. Soldiers were deployed under Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron to construct the road. Redoubts were also built - the Queen's Redoubt at Pōkeno and a stockade above the Waikato River at nearby Havelock’s Bluff. The perception was that: "Governor George Grey had been professing peace while constructing a military road south from Auckland to the lower Waikato, and a military barracks at Kohekohe, within the King's boundary". (Dictionary of New Zealand biography). During a meeting held on 11 Oct 1862 at Tamihere's pa at Peria, east of Matamata, both Tamihana and Toetoe spoke out against the building of the road at Maungatawhiri and Whaingaroa.

Construction of a road to Waikato, Pokeno Hill

Alexander Turnbull Library

THE ROADS AND THE MILITARY. (Taranaki Herald, 13 January 1862)

National Library of New Zealand

Camp of the 65th Regiment near Drury, Auckland

Alexander Turnbull Library

Tamihana and Toetoe spoke out about the building of the road.

MAORI REPORT OF THE SPEECHES AT THE MEETING AT PERIA. (Taranaki Herald, 20 December 1862)

National Library of New Zealand

CHAPTER 6: RIVAL NEWSPAPER SET UP in TE AWAMUTU, Feb 1863

(A) Governor Grey wanted a Waikato newspaper

To answer the arguments of the Hokioi newspaper edited by Patara Te Tuhi, Governor George Grey was keen to have a newspaper published in the Waikato. In February 1863, the Government set up a rival Māori newspaper at Te Awamutu with a Hopkinson-Cope printing press obtained from Sydney. (See article: Cameron, W.J. (1958). "A printing press for the Maori people". Journal of the Polynesian Society, (67,2): pp. 204-210.)

Gov Grey called for a rival newspaper to be set up in the Waikato & a printing press was obtained from Sydney.

Te Pihoihoi printing press

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

The newspaper was printed at Gorst's Otawhao Mission Station school near Te Awamutu.

Mission Station Otawhao. Revd. T, Morgan's.

Auckland Libraries

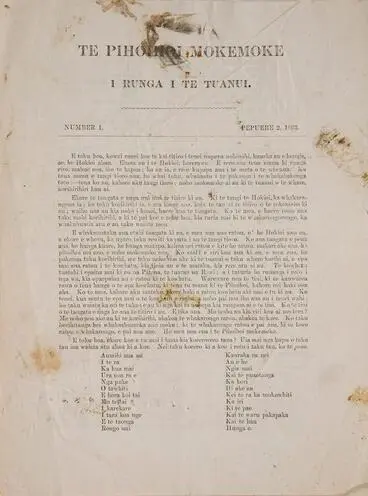

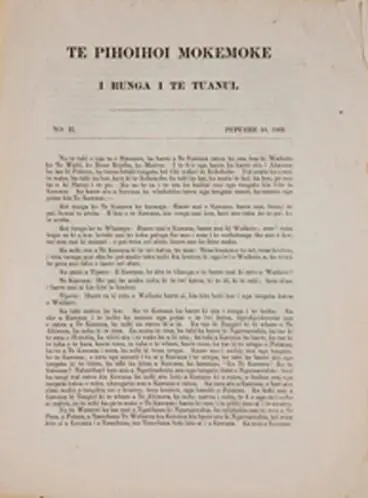

(B) Te Pihoihoi newspaper published Feb - MArch 1863

Te Pihoihoi Mokemoke i Runga i te Tuanui was thought to have taken its name from Psalm 102:7 ('I watch, and am as a sparrow alone upon the house-top'). As reported by the Daily Southern Cross, "Mr. Gorst called his the Pihoihoi, the name of a little ground lark, but which would represent to the native mind, the idea of " the lively sparrow."" (See Papers Past)

The Colonist announces that Gorst is starting a new newspaper to rival "Te Hokioi" (10 Feb 1863).

WAIKATO. (Colonist, 10 February 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

(C) Editor: John Gorst

The editor was John Gorst who had been appointed Waikato Civil Commissioner in 1863. His technical supervisor was Edward John von Dadelszen (1845-1922), who had learned his craft printing for the Melanesian mission under Bishop George Selwyn. (See Te Ara). As stated by Fletcher, "The 'most forcible and idiomatic' Maori language used in the newspaper (distributed gratis) was the work of Miss Ashwell, born in New Zealand as the daughter of the missionary Benjamin Yates Ashwell" (See Fletcher, John (1984). "From the Waikato to Vienna and Back: How two Maoris learned the printing trade". BSANZ Bulletin (vol 8, no.3). pp. 147-155). Miss Ashwell was twenty years old and her parents had the missionary at Kaitotehe, opposite Taupiri.

Miss Ashwell, who was a missionary daughter, wrote the 'most forcible and idiomatic' Māori language.

Ade, Eduard, fl 1865 :Mission du Taupiri, ecole de Maoris - D'apres M. F. de Hochstetter. [1865]

Alexander Turnbull Library

Editor John Gorst was assisted by his technical adviser Edward John Dadelszen

3/4 length seated portrait of Sir John...

Auckland Libraries

(D) Newspaper was pro-Government

Te Pihoihoi newsaper put forward Governor George Grey's argument that there could not be two governments in authority over one country. As was reported by the Daily Southern Cross newspaper (30 July, 1864), Gorst "commenced the publication of a political newspaper of the most irritating and annoying character — something between an Eatonswill Gazette, a feeble Saturday Semew, and a Punch without illustrations. The avowed object of this was to assail the "king movement"." (See Papers Past)

Te Pihoihoi was described as "a bad mocking-bird".

MAORIS OF NOTE IN TOWN. (Auckland Star, 11 February 1889)

National Library of New Zealand

(E) First issue edited by Governor Grey

Governor Grey personally edited the first issue (2 February 1863). [English translation]: "My friend, or whoever reads this small newspaper, make no mistake for I am a Hokioi, but not Te Hokioi, not at all. That bird flies high in the heavens beyond the clouds; while I, fly close to the ground. That bird's screech is an omen, predicting warfare and bloodshed: 'I, on the other hand, do not screech; I sit alone on the rooftop, singing merrily." The article was entitled. “The Evil of the King Movement,” and it criticised a letter from King Tāwhiao—or Matutaera (Methusaleh), as he was then generally known—to the Governor, dated 8th December, 1862, which had been printed in the “Hokioi”, and which inquired what evil had been done by the King and on what account he was blamed. The “Pihoihoi” gave an answer to these inquiries from the Government point of view. (See James Cowan, The old frontier, p.26)

WAIPA. (Daily Southern Cross, 30 April 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

CHAPTER 7: media war ensued between the newspapers!

(A) Bickering between the two newspapers

As was reported by the Daily Southern Cross newspaper (30 July, 1864) , "Great were the bickerings of the two birds; and probably the sparrow, which chirped under the auspices of the Cambridge wrangler, had the best of the argument. At all events, the natives began to think so, and they determined to part the combatants."

WAIPA. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) February 18th, 1863. (Daily Southern Cross, 23 February 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

WAIPA. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) March 1, 1863. (Daily Southern Cross, 09 March 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

UPPER WAIKATO. (Taranaki Herald, 25 April 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

(B) Rewi Maniapoto seizes Te Pihoiho printing Press, March 1863

Te Pihoihoi newspaper's criticism of King Tāwhiao in an article entitled 'Te Kino o Te Mahi Kingi' [The Audacity of Setting up a King] incensed Ngāti Mahuta and their allies. On 24 March 1863, an armed party of 80 men led by Rewi Maniapoto and Aporo Taratutu arrived at the printing office. Rewi, who had intended to kill Gorst, was persuaded by Wiremu Tamihana (Ngāti Haua leader) not to spill Pākehā blood. They sacked the building and carried off the press, the type and copies of the fifth (and last) issue. Gorst and his assistant had been absent and returned to find the press had been removed. Thirty of King Tāwhiao's soldiers were encamped at the gate, and sentinels posted all round the house to prevent any one from setting fire to the buildings or stealing any of Gorst's property.

Te Pihoihoi newspaper's criticism of King Tāwhiao incensed Ngāti Mahuta and their allies.

Portrait of King Tawhiao

Alexander Turnbull Library

Rewi Maniapoto led an armed party to seize Gorst's printing press.

Drawing of Rewi Maniapoto

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Chapter XV — Rewi Maniapoto - New Zealand Revisited

Victoria University of Wellington

(C) Gorst ordered by Rewi to leave Te Awamutu

Gorst was ordered by Rewi to leave Te Awamutu which was seen as a challenge to the authority of Governor Grey. According to Patara Te Tuhi (rival editor of Te Hokioi) not all King Movement supporters agreed with Rewi's action; amongst those opposed were Wiremu Tamihana and Wiremu Toetoe Tumohe. When Gorst reached Ngāruawāhia, Te Tuhi gave him bed and lodging before he continued onto Auckland. Gorst was then briefly employed as private secretary to the native minister, Francis Dillon Bell, before accompanying him to Sydney in August to recruit military settlers. Gorst then returned to England later in 1863.

An account of Rewi's seizure of the newspaper.

SIR JOHN CORST. (Grey River Argus, 23 October 1906)

National Library of New Zealand

An account by Mr F. G. Moore who had worked with Gorst in the Native Department.

THE WAIKATO WAR. (Wairarapa Daily Times, 13 July 1911)

National Library of New Zealand

Rewi's attack against Gorst, and viewpoint of Tamihana and Toetoe.

WAIPA. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) March 26, 1863. (Daily Southern Cross, 06 April 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

(D) Varied accounts of what happened appeared in newspapers

Newspapers throughout NZ commented on Rewi's seizure of Gorst's printing press, with varying details and some reproducing text from other newspapers. The Daily Southern Cross also wrote an article about "Dishonest journalism" (24 April 1863).

THE WAIKATO. (Daily Southern Cross, 27 March 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

AUCKLAND. (Taranaki Herald, 04 April 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

RAGLAN. ( FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) April 6th, 1863. (Daily Southern Cross, 30 April 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

GENERAL SUMMARY. (Daily Southern Cross, 06 April 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

The Daily Southern Cross. (Daily Southern Cross, 06 April 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

POLITICAL GENERAL. (Otago Daily Times, 18 April 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

AUCKLAND NEWS IN CANTERBURY.-DISHONEST JOURNALISM. (Daily Southern Cross, 24 April 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

(E) Gorst's own account of seizure of his newspaper

In one of Mr. Gorst's official reports, printed in the Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, there is a reference to the seizure of the printing press at Te Awamutu. "A few days after that event, the natives offered to restore the press if Mr. Gorst would send about four miles for it. This he refused to do, and gives the following reasons for his refusal : — " Ist, because it seems right that those who took the property away should bring it back themselves ; and 2ndly, because it is not our policy at present to lessen the wrongs which we are suffering at the hands of the Ngati maniapoto." No, " Let them lay up for themselves wrath against the day of wrath." (See Papers Past)

MR. GORST AND TUB MAORI KING. (Daily Southern Cross, 30 July 1864)

National Library of New Zealand

(F) Opposing views about the newspapers' rivalry appeared in the media

As was opinioned by the Daily Southern Cross, "FitzGerald, of Canterbury, in commenting on this event in the- House of Representatives, justified the action taken by the natives, and said that if any one had attempted to set up an opposition paper at Tralee, the "fine pisantry who live there, would not only have broken the press, but the head of the Editor and printer devil into the bargain." (See Papers Past) Other newspapers commented, "It is not surprising that the next step taken by the king natives was to order Mr. Gorst and his fellow occupants of the nest of the " lively sparrow " to leave the district altogether. The Governor had told Thompson that he did not intend to attack the king, but would dig round him. " Mr. Gorst," said they, "is one of the Governor's spades : he must go." (See Papers Past)

WAIKATO. REVIEW OF 1863. (Otago Witness, 13 February 1864)

National Library of New Zealand

Front Cover - The Maori King: Or, the Story of Our Quarrel with the Natives of New Zealand

Victoria University of Wellington

(G) Te Hokioi newspaper ceased publication, 21 May 1863

With the pending outbreak of the Land Wars between the Government and Waikato people, Te Hokioi newspaper ceased publication. The last issue was printed on 21 May 1863. The printing press was shifted by waka to Te Kopua, near a Wesleyan mission station, for safekeeping. Although it reportedly fell into the river along the way, it was recovered.

The printing press was shifted by waka to Te Kopua, near a Wesleyan mission station, for safekeeping.

Drawing of the Te Kopua Wesleyan Mission Sataion...1855

Auckland Libraries

Describes a visit to Ngāruawāhia, which included seeing the printing-office and that the press had been taken away.

THE NATIVE REBELLION, (Colonist, 22 December 1863)

National Library of New Zealand

Chapter 8: Events leading to outbreak of WAIKATO War

(A) King movement challenged building of barracks near Meremere, 1863

Early in 1863, King Tāwhiao warned Wiremu Te Wheoro, a government supporter, not to proceed with the construction of the constabulary barracks that he had given permission to be built on his land at Te Koekoe, upstream from Meremere on the Waikato River. Many of the locals thought the size of the timbers suggested that a military blockhouse was intended. When Te Wheoro ignored the warnings, supporters of the King, led by Wi Kumete Te Whitiora, made the carpenters from Auckland flee. The timber was rafted down the Waikato River where they handed it back to the government redoubt at Te Ia (Havelock, near Mercer), at the junction with the Mangatawhiri River. Patara Te Tuhi (newspaper editor) later said that it was he who first proposed sending the timber back to Te Ia, but he had not anticipated the violence that would follow. (See Gorst, The Maori King (1864), pp. 333-335.)

(B) New Zealand Settlements Act, 9 July 1863

The New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 was passed on 9 July. Governor Grey called on all Māori living in the Manukau district and north of the Mangatawhiri River (the northern boundary of the Kīngitanga) to take an oath of allegiance to the Crown. Those who refused would "forfeit the right to the possession of their lands guaranteed to them by the Treaty of Waitangi". It was intended that military settlers would be placed on any confiscated land.

The New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

(C) Invasion of the Waikato by British militia, 12 July 1863

Two days after the passing of the New Zealand Settlements Act, Governor Grey announced that military posts would be set up along the Waikato River. On 12 July 1863, Lieutenant General Duncan Cameron and British troops crossed the Mangatawhiri River, which Kīngitanga saw as a declaration of open war.

Naval camp Mangatawhiri.

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

Documentary on the invasion of the Waikato

The New Zealand Wars - Episode 3, The Invasion of the Waikato

NZ On Screen

Chapter 9: AFTERMATH - Toetoe, Paraone, Te Tuhi & Gorst

> Wiremu Toetoe Tumohe (1826-1881)

On his return from Austria, Toetoe was "despatched by the Government to the Waikato on the breaking out of the war, to endeavor to negotiate terms of peace with the rebels, but joined his people" and lost his job as Postmaster. (Evening Post obituary). Toetoe fought on the side of King Tāwhiao and NZ newspapers queried his behaviour at being given such an opportunity to visit Austria, yet opposing Queen Victoria's forces. Toetoe's remarks, reported in 1862, reflected on his European experience - as there were many monarchs in Europe living side-by-side, so could there also be two kingdoms in New Zealand. On 21 February 1864, General Duncan Cameron's 1000-strong force of cavalry and foot soldiers attacked Toetoe's village of Rangiaowhia. Toetoe's land was confiscated by British troops. An article in the Waikato Times (24 Feb, 1881) said, "Toetoe has for some time past been down Waikato, gum-digging and flax-cutting. He was brought up here a few days ago, unwell, and died at Kaipiha yesterday on his way to Hikurangi."

Toetoe supported King Tāwhiao and was involved in raiding parties taking guns from settlers.

WAIPA AND WAITETUNA���IMPORTANT (Daily Southern Cross, 19 November 1861)

National Library of New Zealand

Article mistrustful of Toetoe since the land wars suggests canoes carrying food be checked for transporting guns, 1873.

The Evening Star: WITH WHICH ARE INCORPORATED The Evening News and the Morning News. FRIDAY, MAY 23, 1873. (Auckland Star, 23 May 1873)

National Library of New Zealand

Toetoe described as having ended up siding with Māori as 'blood is thicker than water".

Untitled (Grey River Argus, 02 April 1881)

National Library of New Zealand

An account of Toetoe's life.

ALEXANDRA. (Waikato Times, 24 February 1881)

National Library of New Zealand

> Te Hemara Te Rerehau Paraone (c.1840-1894)

On his return from Austria, Paraone became the commander of Reihana's force of 80 men at Whataroa on the Waipa. According to Gorst, Paraone (known as Hemara) and Toetoa (known as Taati) "both receive money from the Government for finding carriers for the inland mails; Taati's soldiers have the monopoly of the mail from Otawhao to Meremere, and Reihana's men are paid from the fees and fines inflicted in his Court; so that they have a very strong and obvious interest in the vigorous administration of justice."

Paraone is described as a "Maori Beau Brunnel" in a suit with a "scented cambric pocket-handkerchief and walking cane".

TAWHIAO AND HIS CHIEFS. (Star, 02 February 1882)

National Library of New Zealand

The Christchurch Star reported on 2 Feb 1882: "After his return from Europe, Hemara Rerehau was a Maori Beau Brummel of the first water, and might have been seen doing the Queen street pavement in a faultless suit of broad cloth, with scented cambric pocket-handkerchief and walking cane. The instincts of his race were too strong upon him, however, and notwithstanding all he had seen in Austria, Germany, Franco, and England to prove the irresistible power of the pakeha, he cast in his lot with his kingite countrymen in the vain attempt to stem the onward march of civilisation. Squatted yesterday a la Maori, with a shawl thrown carelessly around his loins, few would have recognised in Hemara Rerehau the ex-dandy of the Novara epoch." (See Timespanner)

Gorst in his report describes Hemara (Paraone) as the Colonel of Reihana's regiment.

GENERAL REPORT, BY J. E. GORST, ESQ., ON THE STATE OF UPPER WAIKATO; JUNE, 1862. (Taranaki Herald, 02 August 1862)

National Library of New Zealand

After the Land wars, Paraone became a leader of King Tāwhiao's guards until his death in 1895 at Parawera. Toetoe had organised that the King has his own guards, an imitation of the imperial guards in Austria. There were about 19 young men selected under the leadership of Paraone by King Tāwhiao and other chiefs. King Tāwhiao was taken to Ngāruawāhia before burial on Taupiri Mountain where a guard of honour was performed.

Tāwhiao's tangi: guard of honour

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

> Patara Te Tuhi (c.1825-1910)

Patara Te Tuhi fought against the British during the campaign in the Waikato. He went into exile with King Tāwhiao in 1864. In May 1878, he spoke at a meeting with Governor Grey at Hikurangi, that the King movement was reluctant to begin negotiations with the Government until the confiscation of Waikato lands was discussed. This issue stalemated negotiations until 1881, when Tāwhiao formally submitted to the government at Alexandra (Pirongia), In Jan 1882, Te Tuhi accompanied the King on a tour of the North Island and delivered the King's prepared speech to the crowd attending the civic welcome in Auckland.

THE MAORI NEWSPAPER LITERATURE. (Otago Daily Times 31-8-1910)

National Library of New Zealand

Speeches by King Tāwhiao and others when laying down of arms in 1881.

Kingitanga papers

Alexander Turnbull Library

In 1882, Te Tuhi accompanied King Tawhiau on a tour to the North Island and a reception at Auckland.

TAWHIAO'S VISIT TO AUCKLAND. (Auckland Star, 24 January 1882)

National Library of New Zealand

In 1884, Te Tuhi also accompanied the King as his assistant and secretary to England to deliver a petition to Queen Victoria seeking recognition of tribal sovereignty. Instead, Tāwhiao was received by Lord Derby, Secretary of State for the Colonies. The petition was referred back to New Zealand, where it was ignored. After returning to New Zealand, Te Tuhi lived at Mangere near his brother, Honana Te Maioha. At an intertribal conference at Orakei in 1889, Waikato sent as their representative Te Tuhi and his brother Honana. Te Tuhi also issued proclamations for Mahuta who succeeded Tāwhiao as King in 1894. Te Tuhi had his portrait painted by Charles F. Goldie in 1901. Te Tuhi died at Mangere on 2 July 1910 aged about 85 or 86 years, and is buried at Taupiri. (See Waikato Times, 2 March 2015)

In 1884, Te Tuhi and others accompanied King Tāwhiao to England.

Tāwhiao's trip to London

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Te Tuhi had his portrait painted by Charles F. Goldie in 1901.

Below: C. F. Goldie and Patara Te Tuhi taking a break during the sitting. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, PXA 489 no. 38; image...

Victoria University of Wellington

From a photo by Mr. Boscawen, at Mangere, 1901] — Patara Te Tuhi

Victoria University of Wellington

Te Tuhi died at Mangere on 2 July 1910 aged about 85 or 86 years, and is buried at Taupiri.

Wiremu Patara Te Tuhi

Alexander Turnbull Library

In 1884, Te Tuhi also accompanied the King as his assistant and secretary to England to deliver a petition to Queen Victoria seeking recognition of tribal sovereignty. Instead, Tāwhiao was received by Lord Derby, Secretary of State for the Colonies. The petition was referred back to New Zealand, where it was ignored. In 1884, Te Tuhi also accompanied the King as his assistant and secretary to England to deliver a petition to Queen Victoria seeking recognition of tribal sovereignty. Instead, Tāwhiao was received by Lord Derby, Secretary of State for the Colonies. The petition was referred back to New Zealand, where it was ignored.

> John Eldon Gorst (1835-1916)

After being driven out of Te Awamutu by Rewi and his supporters in March 1863, Gorst went to Auckland. He acted as private secretary to Francis Dillon Bell, the Minister of Native Affairs, while the second Taranaki campaign began and Governor Grey invaded the Waikato. In August 1863, he went to Australia with Bell to assist in recruiting military settlers, and then returned to England. Gorst wrote an account of his time in the Waikato in his book, The Maori King (1864). He entered politics and held various positions including becoming a Tory MP at the time when King Tāwhiao and Te Tuhi travelled to London in 1884. Gorst had tried unsuccessfully to organise a meeting with Queen Victoria and they saw Lord Derby instead. Gorst met his rival editor, Te Tuhi, again in 1906 when he visited New Zealand as the British Commissioner to the International Exhibition in Christchurch. Gorst died in London on 4 April 1916.

Gorst was presented with a bound volume of his newspapers.

SIR JOHN GORST AT AUCKLAND. (Marlborough Express, 08 December 1906)

National Library of New Zealand

A DISTINGUISHED VISITOR (Otago Daily Times 30-10-1906)

National Library of New Zealand

CHAPTER 10: HISTORICAL EXHIBITS

> Te Pihoihoi printing press: Alexander Turnbull Library

The press that produced Te Pihoihoi newspaper was donated by the Government Printing Office to the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington on 2 July 1958.

Te Pihoihoi Mokemoke press was donated to the Alexander Turnbull Library on 2 July 1958.

A 96 year old Printing Press machine

Alexander Turnbull Library

> Hokioi printing press: Te Awamutu Museum

In 1922, the Hokioi press was found rusting on the banks of the Waipa. Versions of what became of the press include: that it was tipped from a boat as it was being moved across the river; that the type was melted down for ammunition, and that it was used to press cakes of torori or homegrown tobacco. Te Awamutu Historical Society members visited the farm in 1935, then owned by C. Washer, to inspect the Hokioi press. It was reported to be dilapidated, with several components missing, including the typeset. Later that year the Society loaded it onto a lorry and stored it at the Waipa Post in Te Awamutu. The then president of the Historical Society, Augie Swarbrick,, remarked that the recovery feat “clearly demonstrated that historical research is not a matter of mental effort only”. The Hokioi press has since been part of the Te Awamutu Museums's collection. (See Te Awamutu Museum)

KING TAWHIAO AND HIS PRINTING PRESS. (Auckland Star, 27 October 1875)

National Library of New Zealand

> Te Hokioi resumes after the NZ Land Wars

In 1922, Alexander McDonnell, a fluent Māori speaker and former militia captain who fought against Waikato during the Land Wars, reprinted Te Hokioi on ‘the Free Press Printing Works’ in Auckland. The format, capitalisation and arrangement of this reprint were quite different from the original, and several of the letters are not reprinted. (See Papers Past)

> Both newspapers are a part of newspaper literature heritage

Niupepa [electronic resource] = Māori newspapers.

National Library of New Zealand

Newspaper: Te Hokioi (E rere atu-na), NGARUAWAHIA, Hune 15, 1862-3

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

Newspaper – Te Pihoihoi Mokemoke i runga i te Tuanui, No 1, Pepuere 2, 1863

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

Newspaper – Te Pihoihoi Mokemoke i runga i te Tuanui, No 2, Pupuere 10, 1863

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

Newspaper – Te Pihoihoi Mokemoke i runga i te Tuanui, No 3, Pepuere 23, 1863

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

Newspaper – Te Pihoihoi Mokemoke i runga i te Tuanui, No 4, Maehe 9, 1863

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

Newspaper – Te Pihoihoi Mokemoke i runga i te Tuanui, No 5, Maehe 23, 1863

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

> And what happened to the Frigate Novara?

As noted in Timespanner: "As for the frigate Novara, built from 1843-1851, it was converted to steam-screw in 1861, was involved at the Battle of Lissa in 1866, and conveyed the body of Emperor Maximillian of Mexico home for burial in the Hapsburg crypt in Vienna in 1867. Refitted 1870-71, it was primarily used for sail training until 1876, when converted to a hulk. It was a gunnery training ship from 1881, stricken in 1898, and finally scrapped in 1899."

A CONTEST OF IRONCLADS. THE BATTLE OF LISSA. (North Otago Times, 15 June 1898)

National Library of New Zealand

Further information:

Documentary film:

"The Flight of Te Hookioi: from the Waikato to Vienna in 1859" Producer: Alexander Behse; Director: Tearepa Kiha (2013). See background information to the making of the film in a NZ Herald article by Chris Barton, "Strangers in a strange land: Toetoe and Te Rerehau in Vienna" (17 Oct 2009).

Articles:

Cameron, W.J. (1958). "A printing press for the Maori people". Journal of the Polynesian Society, (67,2): pp. 204-210.

Fletcher, John (1984). "From the Waikato to Vienna and Back: How two Maoris learned the printing trade". BSANZ Bulletin (vol8, no.3). pp. 147-155.

Books:

Cowan, James (1955). ‘The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64)’. (Wellington: R E Owen): Chapter 26.

Gorst, J.E. (1864). The Maori King.

Hochstetter, Ferdinand (1864). New Zealand: Its Physical geography, Geology and Natural History (Stuttgart: Cotta); The Geology of New Zealand, In Explanation of the Geographical and Topographical Atlas of New Zealand (Auckland: T. Delattre).

Hogan, Helen (ed.) (2003). Bravo, Neu Zeeland: Two Maori in Vienna 1859-1860 (Christchurch: Clerestory Press).

Sauer, Georg (2018). The Viennese visit of Toetoe and Rerehau 1859-1860. (Mente Corde Manu Publishing)

Scherzer, Karl Karl von (1861-3). Narrative of the Circumnavigation of the Globe by the Australian Frigate Novara (London: Saunders, Otley & co)

Websites:

Papers Past: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/hokioi-o-nui-tireni-e-rere-atuna

Papers Past: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/pihoihoi-mokemoke-i-runga-i-te-tuanui

Te Ara: https://teara.govt.nz/en/maori-newspapers-and-magazines-nga-niupepa-me-nga-moheni

Te Awamutu Museum: http://tamuseum.org.nz/te-hokioi-rere-atu-na-hokioi-press/

Waikato Museum: https://collection.waikatomuseum.org.nz/objects/21049/newspaper-te-pihoihoi-mokemoke-i-runga-i-te-tuanui-no-2-pupuere-10-1863

![[untitled figure] - The Old Frontier : Te Awamutu, the story of the Waipa Valley : the missionary, the soldier, the pioneer farmer, early colonization, the war in Waikato, life on the Maori border and later-day settlement Image: [untitled figure] - The Old Frontier : Te Awamutu, the story of the Waipa Valley : the missionary, the soldier, the pioneer farmer, early colonization, the war in Waikato, life on the Maori border and later-day settlement](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz%2Fwebarchive%2F20201108000000mp_%2Fhttp%3A%2F%2Fnzetc.victoria.ac.nz%2Fetexts%2FCowOldF%2FCowOldF_091a.jpg&resize=368%253E)

![From a photo by Mr. Boscawen, at Mangere, 1901] — Patara Te Tuhi Image: From a photo by Mr. Boscawen, at Mangere, 1901] — Patara Te Tuhi](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz%2Fwebarchive%2F20201108000000mp_%2Fhttp%3A%2F%2Fnzetc.victoria.ac.nz%2Fetexts%2FCow01NewZ%2FCow01NewZ240a.jpg&resize=368%253E)