New Zealand before He Whakaputanga - Declaration of Independence

A DigitalNZ Story by Janice

A series of important events before the signing of He Whakaputanga - Declaration of Independence.

1642- Abel Tasman sights New zealand

On 13 December 1642 the Dutch sighted ‘a large land, uplifted high’ – probably the Southern Alps. After sighting land, Tasman’s ships veered south, then turned north to pass Cape Foulwind and Cape Farewell. He sailed around Farewell Spit into what is now called Golden Bay, where he anchored on 18 and 19 December.

Source: John Wilson, 'European discovery of New Zealand - Abel Tasman', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/european-discovery-of-new-zealand/page-2 (accessed 30 July 2019)

1769 - James Cook sights New Zealand

James Cook’s ship the Endeavour was a relatively small vessel of 368 tons, just 32 metres long and 7.6 metres broad. It departed from Plymouth on 26 August 1768 with 94 men, entering the Pacific around Cape Horn. After almost four months in Tahiti, from mid-April to mid-August, the Endeavour sailed south into uncharted waters. On 6 October 1769 a cabin boy sighted land.

Two days later Cook landed at Poverty Bay.

Source: John Wilson, 'European discovery of New Zealand - Cook’s three voyages', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/european-discovery-of-new-zealand/page-5 (accessed 30 July 2019)

From 1769 - Interest in New Zealand from the French - (Jean Francois Marie De Surville, Marc Joseph Marion du Fresne, D’Entrecasteaux, Duperrey and Dumont d’Urville).

Captain Jean François Marie de Surville had left India on the St Jean Baptiste in March 1769 for a voyage of trade and exploration to the South Pacific. Sailing via Malacca and the Solomon Islands, he reached the western coast of New Zealand (he was the first European to see it since Tasman) on 12 December 1769.

Not far behind Cook and de Surville came another Frenchman, Marc Joseph Marion du Fresne, who had served on French India Company ships. After landfall at New Zealand’s Cape Egmont, he sailed around the top of the North Island.

In March 1793 Antoine Raymond Joseph de Bruni d’Entrecasteaux, commanding the Espérance and the Recherche, sailed past New Zealand while searching for another French explorer, Jean François de Galoup, Comte de la Pérouse.

Louis Isidore Duperrey sailed from Toulon on the Coquille in 1822. By 3 April 1824 he had reached the Bay of Islands, where he stayed until 17 April before continuing his circumnavigation.

Dumont d’Urville came with the intention of completing Cook’s chart of New Zealand. He went on to examine the east coast from Cape Campbell to Whāngārei Harbour, a journey that included the Hauraki Gulf, Waitematā Harbour and Coromandel Peninsula.

Source: John Wilson, 'European discovery of New Zealand - French explorers', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/european-discovery-of-new-zealand/page-8 (accessed 30 July 2019)

Plaque to the ‘St Jean Baptiste’ anchoring at Doubtless Bay, 1769

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

One of de Surville’s anchors

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

1791 Whalers and sealers

Māori probably did not hunt whales before Europeans arrived. But if they found one washed up on a beach they would cut it up for food.

The first whaling ship, from America, came to New Zealand waters in 1791. Over the next 10 years, the seas around New Zealand became a popular place to catch whales.

Whales were hunted for their oil, baleen and ambergris. The oil was used in lamps and machinery. Baleen hangs inside the whale's mouth to catch krill and other food, and was used to make corsets and whips. Ambergris forms in the whale’s belly and was an ingredient in expensive perfumes.

Source: Jock Phillips, 'Whaling', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/whaling (accessed 13 August 2019)

Simeon Lord

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Simeon Yates

Most of the sealing in New Zealand was organised by Sydney companies, nearly all founded by ex-convicts such as Simeon Lord. A few American captains and ships were used, to avoid restrictions applied by the East India Company, who had a monopoly on sealing in the area. The men were a tough breed of ‘sea-rats’, some former sailors, others ex-convicts. Some joined gangs after stowing away on ships from Sydney.

Source: Jock Phillips, 'Sealing - The sealers', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/artwork/6227/simeon-lord (accessed 13 August 2019)

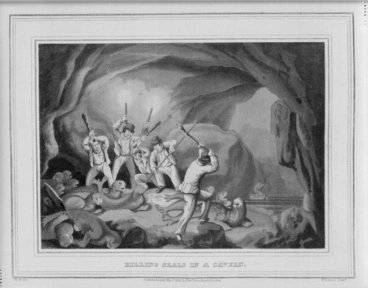

An illustration showing the killing of seals in a cavern

Auckland Libraries

Sealing operations close to mainland New Zealand were in Fiordland or around Foveaux Strait.

Map of sealing places

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

1814 - Missions and Missionaries

Missionaries were based in New Zealand from 1814, and many were vitally important cultural go-betweens.

English missionary Samuel Marsden first arrived in the Bay of Islands in 1814. He was accompanied by Ruatara, a local chief returning to his own people; fellow missionaries William Hall, a joiner, John King, a ropemaker, and schoolmaster Thomas Kendall; and others including Thomas Hansen.

Source: Mark Derby, 'Cultural go-betweens - Missionaries', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/cultural-go-betweens/page-3 (accessed 13 August 2019)

Thomas Kendall

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Te Waitere was the site of a Wesleyan mission station.

Te Waitere

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

1831 - Letter to King William IV

This letter was sent to King William IV by 13 Māori chiefs from the Bay of Islands in 1831. Its main aim was to seek the king's protection against the French, who had recently sent a naval vessel to New Zealand. The chiefs were also concerned about inter-tribal conflict and the misconduct of British subjects, and wanted the king to defend them against lawlessness so everyone could live peaceably together.

Source: Basil Keane, 'He Whakaputanga – Declaration of Independence - Background to the declaration', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/zoomify/35114/1831-letter-to-king-william-iv (accessed 30 July 2019)

1831 letter to King William IV

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

1810 - 1840 Musket wars

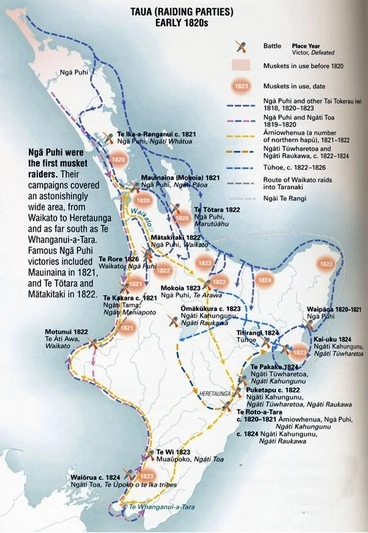

The musket wars were a series of Māori tribal battles involving muskets (long-barrelled muzzle-loaded guns, brought to New Zealand by Europeans). Most took place between 1818 and 1840, although one of the first such encounters was around 1807–8 at Moremonui, Northland, between Ngāti Whātua and Ngāpuhi.

Source: Basil Keane, 'Musket wars - Musket wars overview', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/musket-wars/page-1 (accessed 30 July 2019)

Musket Wars map

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

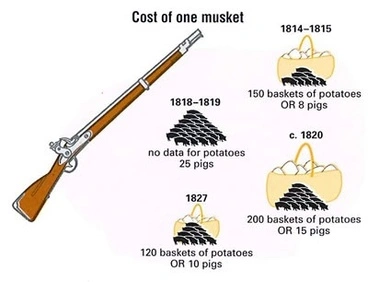

Changing cost of muskets 1814-1827

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

1831 - James Busby appointed British Resident to New Zealand

In the early 19th century European traders, whalers and settlers were increasingly coming to New Zealand. Missionaries, many European settlers and Māori were concerned about lawlessness and the need for some kind of government. The visit of the French ship La Favorite in 1830 led to British concerns about other nations annexing New Zealand.

In 1831, 13 northern chiefs, assisted by missionary William Yate, sent a letter to King William IV requesting his protection. As a result James Busby was appointed as British Resident in New Zealand (an official position). He arrived in 1833, but was not well equipped. He had no army or police force to support him, and he had to use diplomacy to achieve anything. He was described as a man o’ war (warship) without guns.

Source: Basil Keane, 'He Whakaputanga – Declaration of Independence - Background to the declaration', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/he-whakaputanga-declaration-of-independence/page-1 (accessed 30 July 2019)

Europeans involved in the declaration: James Busby

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

1834- United Tribes Flag

This flag was adopted by 25 northern chiefs and their followers in March 1834, in response to the fact that ships from New Zealand were liable to be seized unless they had a flag or certificate representing their country of origin. The adoption of the flag was the first act of Māori in claiming a collective nationhood. Until that time they had been a community of separate tribes.

Source: Fiona Barker, 'New Zealand identity - Understanding New Zealand national identity', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/artwork/34597/united-tribes-flag (accessed 30 July 2019)

Busby called together a number of northern chiefs to vote for a national flag. Three options were presented, which had been organised by missionary Henry Williams. On 20 March 1834, at Waitangi, the chiefs selected one which became known as the United Tribes’ flag. It received a 21-gun salute, and was eventually recognised by the British king and became a national flag for ships from New Zealand.

Source: Basil Keane, 'He Whakaputanga – Declaration of Independence - Background to the declaration', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/he-whakaputanga-declaration-of-independence/page-1 (accessed 30 July 2019)

United Tribes' flag

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

1834- More Concern about interest from france and the United states

As well as concerns about lawlessness, there had also been concerns about the interest in New Zealand shown by France and the United States. This came to a head in 1834 when a French national, Charles Philippe Hippolyte de Thierry was known to be heading to New Zealand with a plan to declare a sovereign and independent state of Hokianga.

Source: Basil Keane, 'He Whakaputanga – Declaration of Independence - Background to the declaration', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/he-whakaputanga-declaration-of-independence/page-1 (accessed 30 July 2019)

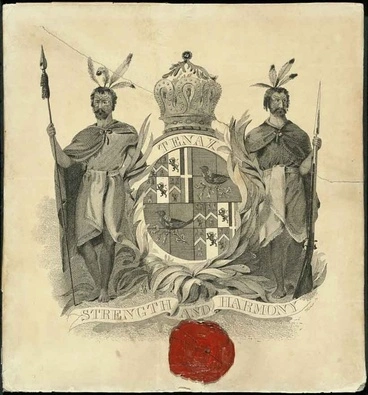

Coat of Arms by Charles Philippe de Thierry

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

1834- 1835 Europeans involved in the Declaration of Independence- James Busby, Henry Williams and William Colenso

Europeans involved in the declaration: William Colenso

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

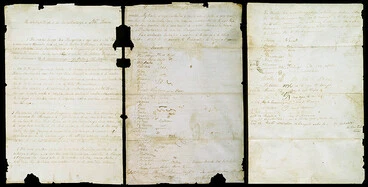

28 October 1835 - He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga 0 Nu Tireni

On 28 October 1835 the declaration was signed by 34 northern chiefs. Signatures continued to be added until 1839, by which time it had 52 signatures. These included the signatures of Te Wherowhero, the chief of Waikato who would later become the first Māori king, and chief Te Hāpuku, of Ngāti Kahungunu.

Source: Basil Keane, 'He Whakaputanga – Declaration of Independence - Background to the declaration', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/he-whakaputanga-declaration-of-independence/page-1 (accessed 30 July 2019)

He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni (known as The Declaration of Independence), 1835

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Printed Version of He W[h]akaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene, 1837

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Some Signatories to the declaration

Tawhiao Matutaera Potatau te Wherowhero

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

Signatories to the declaration: Te Hāpuku

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Te Waru

Alexander Turnbull Library

![Printed Version of He W[h]akaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene, 1837 Image: Printed Version of He W[h]akaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene, 1837](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Flive.staticflickr.com%2F5695%2F23627028482_80aa05f411_z.jpg&resize=368%253E)