Epidemics and Pandemics: Impact on Māori

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library Services to Schools

Māori were affected by the epidemics and pandemics that have swept through Aotearoa more severely than other groups. This story examines the impact of European diseases on Māori and some of the people that made a difference in their communities.

BACKGROUND

In pre-European times, Māori were tall and muscular, even by today’s standards. Their average life expectancy of around 28–30 years seems low. But when European explorer James Cook arrived in New Zealand, the populations of both France and Spain had a life expectancy below 30 years.

Early European visitors often described Māori as a fit and healthy people. They led active lives, and many of the infectious diseases common in other parts of the world were unknown to them. However they were probably affected by pneumonia, tetanus, gastroenteritis, arthritis, rheumatism and various skin diseases.

Source: Te hauora Māori i mua – history of Māori health - Pre-European health, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, (accessed 21 April 2020)

CONTENTS

- Effects of colonisation on Māori health

- Cause of Māori population decline

- Māori beliefs about ill health

- The 1918 Influenza Pandemic

- The impact of other diseases

- Infant mortality

- Attitudes towards Māori

- Maui Pōmare & Te Rangi Hīroa (Sir Peter Buck)

- Māori nurses

- Glossary

- Supporting resources.

The first Europeans to arrive here found thriving Māori communities with life expectancies on a par with Europeans.

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

EFFECTS OF COLONISATION ON MĀORI HEALTH

Māori started the epidemiological transition (in which diseases of old age and lifestyle replace infections as the main cause of death) much later than Pākehā, because of the effects of colonisation on their disease and death rates.

By 1891 the estimated life expectancy of Māori men was 25 and that of women was just 23.

The Māori population also declined steeply. It is estimated to have been about 100,000 in 1769. By 1840 it was probably between 70,000 and 90,000. At its lowest point in 1896 it was around 42,000.

Source: Death rates and life expectancy - Effects of colonisation on Māori, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, (accessed 20 April 2020)

Deaths from infectious diseases were common in Māori communities by the time this photograph was taken in around 1890.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

CAUSE OF MĀORI POPULATION DECLINE

There is a common belief that musket warfare between 1810 and 1840 caused heavy mortality among Māori. However, war deaths were not great in number compared with the deaths from other causes. From 1810 to 1840 there were around 120,000 deaths from illness and other ‘normal’ causes, an average of 4,000 a year. In the same period warfare caused perhaps 700 deaths per year.

Introduced diseases were the major reason for the Māori population decrease. In the 1890s the Māori population had fallen to about 40% of its pre-contact size. Decline accelerated after the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 and settlers began to arrive in greater numbers. This influx exposed Māori to new diseases, leading to severe epidemics.

Source: Death rates and life expectancy - Effects of colonisation on Māori, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, (accessed 20 April 2020)

Poor quality housing increased the risk of infection for many Māori.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

MĀORI BELIEFS ABOUT ILL HEALTH

Māori medical treatment was closely linked to religious beliefs and practices. People became ill when they offended the gods, or violated the tapu associated with the supernatural world. Scientific ideas about hygiene and infection were little understood anywhere in the world. Nevertheless Māori belief in tapu played an important role by guiding practices for sanitation and water supply. For example, the turuma (latrine) was a separate space in Māori villages. Tapu also affected childbirth and death ceremonies, ensuring healthy practices. Tapu limited contact with the dead, which helped prevent the spread of disease.

Source: Te hauora Māori i mua – history of Māori health - Pre-European health, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, (accessed 21 April 2020)

Juice from the flowers of the tutu plant was used as an antiseptic to treat wounds and bruises as well as to set bones.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

QUICK FACTS

- Illnesses of all kinds were treated with a range of medicinal plants known for their specific healing properties; this is known as rongoā.

- Tohunga, spiritual leaders, would use rituals and karakia to treat patients. They were considered vital to the process of healing.

- Some illnesses were considered mate tangata, being caused by human actions like violating tapu for example.

- Massage and immersion in water were also part of treatment; immersion in water hastened many deaths during the influenza pandemic of 1918.

THE 1918 INFLUENZA PANDEMIC

The official Māori death rate of 42.3 per 1,000 people was more than seven times that of the Pākehā population. It is an underestimate, given the incompleteness of Māori death registrations.

Source: Epidemics - The influenza era, 1890s to 1920s, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand,(accessed 22 April 2020)

Aperatama Rupene wrote to the editor of the Auckland Star in December 1918 with a heartfelt account of the impact of the epidemic on Māori communities. Descriptions of how Māori were hit by the flu are fairly rare, making this a valuable letter.

Rupene expressed concern that the health authorities had not shown sufficient foresight. Many Māori communities were being left to ‘rely upon their own knowledge of herbs and remedies to cope with the dread scourge’.

Source: The 1918 influenza pandemic – Māori and the flu, 1918–19, NZHistory.

First world war soldiers infected with influenza were quarantined at Somes Island off the coast of Wellington.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

QUICK FACTS

- Māori fatalities during the 1918 flu pandemic were at least 7 times that of Europeans.

- Monuments to those who succumbed to the disease in Northland and Hawkes Bay support the idea that many deaths in Māori communities were not recorded, as many of the names that appear on these monuments are not on official death registers.

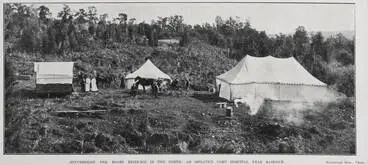

- Health officials often sought to separate sick Māori from Europeans, and as a result, many temporary hospitals were set up in marae around the country, such as at Te Tokanganui-a-noho at Tu Kuiti.

- The King Country area was particularly hard hit by the pandemic; by November 30, 1918, the recorded death toll stood at 118.

- Along with other soldiers from Aotearoa, men in the Pioneer Māori Battalion died from influenza; some of them away from whānau in hospitals in England and Europe.

An influenza warning

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Māori Battalion in Italy, winter 1945

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Omaio Māori School - 1918 Influenza

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

THE IMPACT OF OTHER DISEASES

When Europeans arrived diseases such as measles, influenza, typhoid fever and tuberculosis decimated local tribes who had no immunity to these illnesses. Māori who had limited contact with Europeans were less badly hit.

As more Europeans arrived, all tribes were affected by disease. The loss of their land through confiscation and sales left people with poor housing, dirty water supplies and an unhealthy diet. The Māori population probably halved from its 1840 level. It began to grow again in the 1890s. People developed immunity to diseases, and the government provided some medical care.

Source: Te hauora Māori i mua – history of Māori health - Health devastated, 1769 to 1901, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, (accessed 22 April 2020)

This image of the typhoid camp at Maungapōhatu in the Urewera shows the poor quality of the facility.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

QUICK FACTS

- In 1875 deaths from typhoid among Māori were recorded at 323, however, fatalities reduced for Europeans as sanitation and water quality improved, while Māori continued to be affected by this disease well into the 20th century.

- In 1913 a smallpox epidemic hit Northland Māori communities, brought on a ship arriving from America by a Mormon missionary; 55 people died.

- Measles affected Māori greatly, for example, the population of Upper Hutt was hit by an epidemic at the beginning of 1857 that lasted three years; by the time it had passed, less than 300 Māori remained.

- Many diseases such as whooping cough, measles, influenza and diphtheria recurred every 3-5 years in Māori communities during the 1800s.

The Scourge Of The Backblocks

Auckland Libraries

Measles at Parihaka

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Becky and Kino, from settlement near Maoribank bridge.

Upper Hutt City Library

INFANT MORTALITY

Many Māori children died in their first year of life, often from pneumonia and respiratory infections. In addition, many adults and older children suffered from epidemics of viral disease and typhoid fever, as well as from tuberculosis, a chronic disease that often ended fatally.

Infant mortality was much higher among Māori than in the non-Māori population. In 1938 it was four times higher.

The number of native health nurses (known as district health nurses from 1930, and public health nurses from 1952) increased, and they gave added emphasis to preventive work and to mothers and children. Most Māori births were assisted by relatives or traditional attendants until the 1920s. The Department of Health encouraged hospital births in an effort to reduce the gap between Māori and non-Māori maternal mortality rates. By 1937, 17% of Māori births took place in hospital. This proportion increased rapidly after maternity care became free in 1939. By 1947 about half of Māori births took place in hospital.

Māori infant mortality fell steadily from the late 1940s, although in the early 21st century it was still higher than the non-Māori rate.

Source: Te hauora Māori i mua – history of Māori health - Health devastated, 1769 to 1901, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand (accessed 21 April 2020)

Princess Te Puea Hērangi was a leader in the Waikato region and a strong advocate for Māori children.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

QUICK FACTS

- As early as 1898 the Nelson Mail reported high rates of death among Māori children at Waikaremoana, thought to be caused by influenza.

- Dr Maui Pōmare believed that many Māori children were lost to epidemics through faith in the powers of tohunga or spiritual healers.

- Princess Te Puea saved the lives of many children in the Waikato that were orphaned by the influenza epidemic and also bought up many children herself as whangai.

- It is estimated that the 1918 Influenza pandemic caused 2,091 children to be orphaned.

- Between 1840 and 1900 high numbers of Māori children fell ill with respiratory diseases and died before their first birthdays.

The Vaccination Of A Māori School

Auckland Libraries

Doctor checking Māori family, 1950

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

ATTITUDES TOWARDS MĀORI

At a meeting of the Canterbury Hospital and Charitable Aid Board in late February 1919, in the aftermath of the epidemic, a nasty quip was made about Māori. During a discussion of the need to clean up ‘Maori pas’ to avoid another epidemic, a woman member of the board suggested, ‘Why not start by cleaning up the Māori mas?’ [in other words, Maori women]. This unpleasant play on words led to a rebuke from W.D. Barrett, a Māori from Tuahiwi near Rangiora, who recounted his marae’s experience of the epidemic.

Reports agreed that the epidemic was well managed at Tuahiwi. Despite this, those living there were discriminated against. Christchurch health officials interpreted instructions from the Health Department to mean that Māori could not travel without a permit, which could only be obtained in Christchurch. Some were allowed to board the train, but then put off it and left to make their own way home; one woman had been travelling to visit her sick son in hospital.

Source: The 1918 influenza pandemic – Māori and the flu, 1918–19, NZHistory.

Cartoons such as this portrayed Māori in a discriminatory and racist way.

Auckland Libraries

QUICK FACTS

- Among Europeans, Māori were blamed for epidemics and were accused of being unclean and having lazy habits. The phrase 'Māori Epidemic' was coined.

- Government officials actively sought to keep Māori separated from Europeans, often in isolated camps with insufficient facilities.

- In places, Māori were prohibited from holding tangi to bury their dead, while European funerals were allowed to continue.

- Two beliefs that effected access to proper medical care for Māori were commonly held in the late 1800s - firstly that Māori were a dying race and secondly that they were incapable of reaching the same levels of 'civilisation' as Europeans.

Racist cartoon

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Suppressing The Māori Epidemic In The North

Auckland Libraries

Ridding The Waikato Of The Māori Epidemic

Auckland Libraries

MĀUI PŌMARE & TE RANGI HĪROA (SIR PETER BUCK)

Young Māori activists, many of them former students of Te Aute College in Hawke’s Bay, pushed for improved health practices in Māori settlements around the country, and advocated greater use of the available health-care services and facilities. From the late 1890s they worked through the Te Aute College Students Association (later known as the Young Maori Party), led by Apirana Ngata and others. Many influential chiefs and elders lent their support.

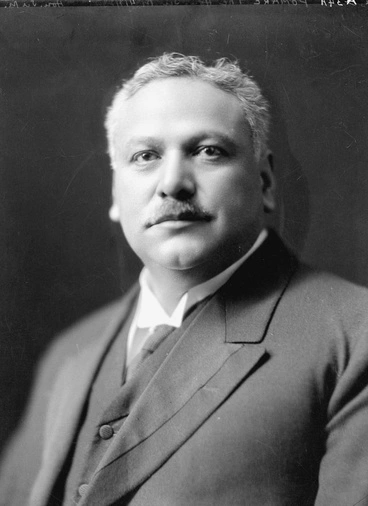

Soon this movement became closely associated with innovative Māori health measures adopted by the government. The new Public Health Department established in 1900 included a Māori section headed by Dr Māui Pōmare, who was appointed native health officer. Until he resigned in 1911 to enter Parliament, Pōmare traveled around the country, inspecting Māori settlements and giving advice, instruction and encouragement to local leaders to improve sanitary and public-health conditions. For some years he had the help of an assistant native health officer, Dr Te Rangi Hīroa (Peter Buck).

Source: Te hauora Māori i mua – history of Māori health - Health devastated, 1769 to 1901, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, (accessed 21 April 2020)

Māui Pōmare and Te Rangi Hīroa, both doctors, were graduates of Te Aute College in the Hawkes Bay.

Wairarapa Archive

QUICK FACTS

- Te Aute College, that still continues to provide education to Māori boys today, was set up in 1854 and has produced many significant Māori leaders.

- English born John Thorndon, the headmaster of Te Aute from 1878 to 1912, was a strong advocate for the academic education of Māori and, unlike most Europeans of the time, believed that Māori were as capable as their European counterparts.

- Māui Pōmare was appointed to the position of Māori Medical Officer in 1901 and was influential in improving sanitation and hygiene in Māori communities. He also campaigned to abolish tohungaism and was a supporter of the Tohunga Suppression Act of 1907.

- After serving as a medical offer in the First World War, Te Rangi Hīroa became director of the Māori Health Division. He worked closely with Māui Pōmare to improve health outcomes for Māori.

Peter Buck (Te Rangi Hīroa) at work

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Maui Pomare

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Māori Council, Maahunui District, 1902

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

MĀORI NURSES

Native health nurses, both Pākehā and Māori, were appointed to the Māori nursing service set up by the government in 1911. A precursor of the public health nursing service of later times, this branch of the Health Department had the strong support of Māori health advocates such as Pōmare, Te Rangi Hīroa and Ngata. The service concentrated on community health work in Māori settlements, many of them remote and without easy access to doctors.

Source: Te hauora Māori i mua – history of Māori health - Health improves, 1900 to 1920, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, (accessed 21 April 2020)

An early scheme to train educated young Māori women for a year at a hospital was hampered by most hospitals' reluctance to co-operate; in 1905, Gisborne refused to accept Māori probationers, and Napier and Wellington would take only one each. The first Māori woman to pass the state nursing examination was Ākenehi Hei, of Te Whānau-a-Apanui, in 1908. By 1911, the Department of Public Health had initiated the Māori health nursing service. A number of Māori women had trained, including Ema Mitchell of Pakipaki, Sarah Burch of Waimā, Eva Wīrepa of Te Kaha, Hēni Whangapirita, 'Pirenga' (probably Pīnenga) Hall, and Hannah Hippolite of Nelson.

By 1914, there were twelve Māori health nurses, both Māori and Pākehā. Their work was 'dangerous and difficult' and they often dealt with epidemics. Their hospital-based training gave them 'no special instruction to prepare them for their work … they had to rely heavily on their own initiative'.

Source: Ngā Rōpū Wāhine Māori – Māori Women's Organisations, NZHistory.

Māori nurses played pivotal roles around Aotearoa during the epidemics and pandemics of the 1800s and 1900s.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

QUICK FACTS

- Until the 1950s Māori predominantly lived in remote rural areas. To see their patients, nurses would often undertake long journeys on horseback.

- Nurses were often the only medical help that Māori communities received, therefore they provided every possible service from helping with births to tending to people ill with infectious diseases.

- Often working alone in communities with limited or no medical supplies, nurses were under a great deal of pressure.

- Māori nurses needed to balance the long-held beliefs about the treatment of disease in Māori communities with their training in European medicine.

Māori nurses

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Nurses at Maori Hospital, Temuka, South Canterbury

Christchurch City Libraries

OTHER RESOURCES

1918 Influenza Pandemic — information from Christchurch Libraries.

1918 Influenza pandemic's devastating impact on Māori — this pandemic caused 9000 deaths and Māori deaths accounted for a quarter to a third of the deaths.

Archives of 1918 show familiar pandemic instructions, and some questionable medical advice — more than 100 years ago, a school teacher in a small north island community wrote to the government to tell them how influenza had hit their village.

District Nurse's Notes — Nurse Cormack with accounts of her life working in Tolaga Bay.

Influenza — Māori suffered heavily during the epidemic. Of an estimated population of 51,000, 2160 died—a death rate of 42.3 per 1000, seven times the overall European death rate.

Influenza Epidemic: Rongo Nuku of Whakatane — the 1890 Influenza epidemic claimed hundreds of Māori lives.

Letters — a personal account of a visit to Oruawharo marae during the smallpox epidemic.

Māori and pacific health practitioners — Māori and Pacific practitioners have always been significantly under-represented in the medical workforce compared to their proportion of the general population.

Maori and the flu, 1918-19 — accounts of the devastation in Māori communities during these difficult times are hard to come by, particularly because Pākehā journalists did not often cover the plight of isolated rural Māori communities during the crisis

Māori health reports reveals poor standards — Māori standards of health are still lower than non-Māori.

Māori medicine — in traditional Māori medicine, ailments are treated in a holistic manner.

Māori Tohungaism — an NZ Herald article from 1904 discussing the role of tohunga in treating illness in Māori communities.

Native Questions — a newspaper from 1913 that suggests tangi should be prohibited.

Natives District Nursing — extracts from the Journal of Nurses of New Zealand from 1915 commenting on the health of Māori communities in Te Araroa and the Bay of Islands.

Ōmāio— how the 1918 influenza outbreak impacted on the Ōmāio marae and district in the Bay of Plenty.

Peaceful armistice, deadly flu — Church Missionary Society member Sybil Mary Lee travelled to Britain and worked visiting Māori soldiers in hospitals in Wandsworth and Walton-on-Thames.

Smallpox epidemic kills 55 — Mormon missionary Richard Shumway arrived at Auckland from Vancouver and infected the local Māori population with smallpox.

Te hauora Māori i mua – history of Māori health — Māori communities were ravaged by the arrival of European diseases such as measles and influenza.

The decline of the Maori — to the Maori, influenza and measles were unknown, and he had no powers of resistance.

The 1918 influenza pandemic — accounts of the devastation in Māori communities during these difficult times are hard to come by

Thousands of 1918 flu pandemic victims listed online — a lot of Māori at the time were living in quite regional areas and what that meant is that getting the help that was maybe necessary to avoid passing away from this pandemic wasn't very easy.

Tuberculosis (TB) disproportionately affecting Māori — Māori continue to suffer disproportionately from the disease compared with others born in New Zealand.

Urutā: COVID-19 Advice for Māori by Māori health experts — Māori doctors and health experts worried about the lack of Covid-19 planning for Māori have banded together to create a national Māori pandemic group, Te Rōpū Whakakaupapa Urutā.

Why equity for Māori must be prioritised during the Covid-19 response — Māori have fared worst in every pandemic New Zealand has seen.

INFLUENTIAL PEOPLE

Akenehi Hei — Akenehi Hei, occasionally called Agnes by her Pakeha employers, was born probably in 1877 or 1878 into a leading Te Whakatohea and Te Whanau-a-Apanui family at Te Kaha, Bay of Plenty.

Jessie Alexander — after the 1918 influenza epidemic, Jessie persuaded the Maori Mission Committee to open a small cottage hospital in Nuhaka.

John Thornton — Thornton was the highly influential headmaster of Te Aute College for Māori boys.

Kāhuipani — based on a true story, Kāhuipani details the journey of two children to the Tuakau bridge to find Te Puea, a young woman who cared for more than 100 orphans during the influenza epidemic of 1918.

Te Kirihaehae te Puea Hērangi — Te Puea was to play a crucial role alongside three successive kings in re-establishing the Kīngitanga.

Māui Pōmare — Māui Pōmare, of Ngāti Mutunga and Ngāti Toa, was born in 1875 or 1876.

Nurse Maud Mataira of Whakatane — Maud was born on 30th September 1884, the second child of Karepa Tukareaho and Matewai Arihi (Alice) Mataira and was baptised shortly afterwards.

Putiputi O'Brien — Whaea Putiputi O'Brien was born and raised in Te Teko. She trained at the Waikato Hospital School of Nursing from 1941-1945 and registered as a General and Obstetric Nurse at the Waikato Hospital in 1945.

Māori made use of hot pools to treat various ailments.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

GLOSSARY

Definitions below taken from the Oxford Learner's Dictionary and Te Aka.

activist — a person who works to achieve political or social change, especially as a member of an organization with particular aims.

advocate — a person who supports or speaks in favour of somebody or of a public plan or action.

colonisation — the act of taking control of an area or a country that is not your own, especially using force, and sending people from your own country to live there.

confiscation — the act of officially taking something away from somebody, especially as a punishment.

discriminate — to treat one person or group worse/better than another in an unfair way.

hampered — to prevent somebody from easily doing or achieving something.

hygiene — the practice of keeping yourself and your living and working areas clean in order to prevent illness and disease.

immersion — the act of putting somebody/something into a liquid, especially so that they or it are completely covered; the state of being covered by a liquid.

immunity — the body’s ability to avoid or not be affected by infection and disease.

mortality — the number of deaths in a particular situation or period of time.

probationer — a person who is new in a job and is being watched to see if they are suitable.

precursor — a person or thing that comes before somebody/something similar and that leads to or influences its development.

respiratory — connected with breathing.

sanitation — the equipment and systems that keep places clean, especially by removing human waste.

TE REO MĀORI

karakia — to recite ritual chants, say grace, pray, recite a prayer, chant.

pā — fortified village, fort, stockade, screen, blockade, city (especially a fortified one).

marae — courtyard - the open area in front of the wharenui, where formal greetings and discussions take place. Often also used to include the complex of buildings around the marae.

tangi — rites for the dead, funeral - shortened form of tangihanga.

tapu — be sacred, prohibited, restricted, set apart, forbidden, under atua protection - see definition 4 for further explanations.

tohunga — skilled person, chosen expert, priest, healer.

whāngai — to feed, nourish, bring up, foster, adopt, raise, nurture, rear.

whānau — extended family, family group.

This story was curated and compiled by Te Puna Mātaurang o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, April 2020.