Māori and the stage and screen

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library Services to Schools

This story provides links to resources about some of New Zealand's significant Māori performers on the stage and screen.

Karetao (puppet), early 1800s

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

TE WHARE TAPERE

Kia kawea tātou e te rēhia

Let us be taken by the spirit of joy, of entertainment

This whakataukī (saying) indicates that performance-based entertainment was central to Māori society long before the first arrival of Europeans. Whare tapere was the name given to sites used for entertainments such as storytelling, dance, music and games. Sometimes this name referred to a special building, but more often a suitable outdoor location such as the base of a notable tree was designated a whare tapere. A whare mātoro was a form of whare tapere that offered entertainment specifically by and for young people. A travelling troupe of entertainers who staged whare tapere in a succession of communities was called a whare karioi.

Source: Māori theatre - te whare tapere hōu - Origins of Māori theatre, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Celebrations in the capital

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

THEATRE

In the 1980s the renaissance of Māori culture brought a spectacular growth of Māori actors on stage and screen. Leading actors such as Jim Moriarty, George Henare and Wi Kuki Kaa moved easily between mainstream European-styled theatre and Māori marae-based theatre. Rawiri Paratene and Rangimoana Taylor were among the early graduates of the New Zealand Drama School in the 1970s.

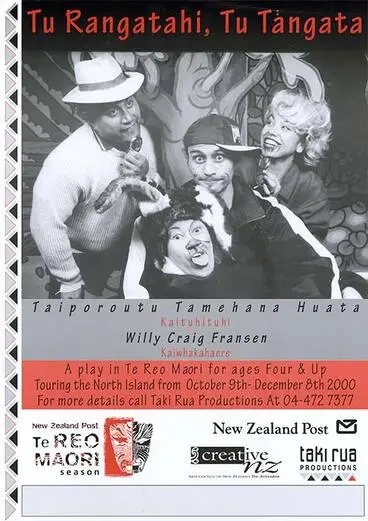

With the formation of Māori theatre groups such as Maranga Mai in Auckland and Taki Rua Theatre in Wellington, the number of Māori actors grew. Taki Rua started as a bicultural company and then became purely Māori with seasons of plays in te reo Māori. In 1988 the New Zealand Drama School changed its name to Te Kura Toi Whakaari o Aotearoa: New Zealand Drama School, and adopted a bicultural approach to teaching drama.

Source: Actors and acting - Multiculturalism and acting, 1980 to 2013, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Māori Troilus and Cressida

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

In the 21st century, Māori theatre has explored genres much wider than agitprop theatre and marae-based traditional stories. Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement, also well-known as screen actors and directors, turned legends into irreverent comedy in The untold tales of Maui, which toured nationally in 2003–4. Tawata Productions premiered Miria George’s science fiction-influenced and what remains in Cambridge, UK, in 2006. Playwrights such as Albert Belz (Awhi tapu, Yours truly, Te karakia) and Whiti Hereaka (Fallow, Te kaupoi, Raw men) have dealt with issues not previously seen as intrinsically Māori.

Source: Māori theatre - te whare tapere hōu - Consolidating Māori theatre, 1990s onwards, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Maori Theatre Trust production of He Mana Toa

Alexander Turnbull Library

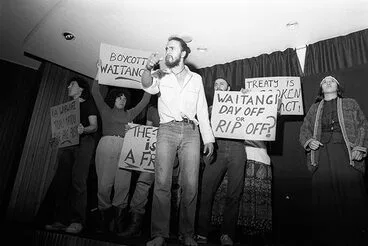

Maranga Mai theatre group performing at the Beehive, 1980

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Te reo Māori theatre, 2000

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

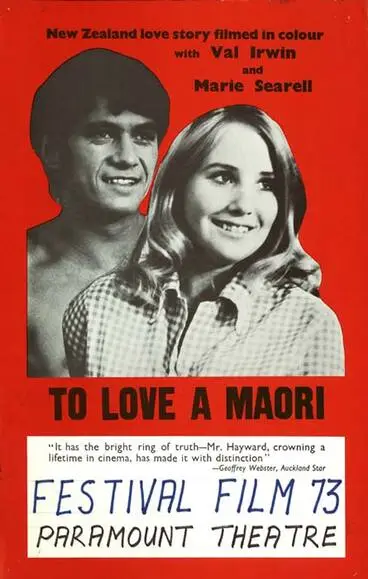

FILM

The earliest films made in New Zealand have been lost due to the fragile nature of film. The first were made in the 1910s by overseas crews. Early films often used Māori culture as an exotic drawcard. Rudall Hayward had a 50-year career in film, beginning with black and white silent films. His To love a Maori (1972) was the first colour feature film made by a New Zealander. He is notable for including a Māori perspective in his films. His first wife Hilda and his second wife Ramai were both important collaborators.

Source: Feature film, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

To love a Maori

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

John O’Shea has been called the father of New Zealand film. He was also interested in looking at race relations in his films, such as Broken barrier (1952).

Source: Feature film, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Broken Barrier cast and crew, Māhia Peninsula

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

In the 1980s, for the first time, students were able to learn film-making skills in tertiary institutions, increasing the potential for documentary projects. The decade also saw production of some important left-wing films, including:

- Bastion Point: day 507 (1980), a powerful work by Merata Mita, Gerd Pohlmann and Leon Narbey, which documented the land-rights occupation of Takaparawhā (Bastion Point) by members of Ngāti Whātua

- The bridge: a story of men in dispute (1981), directed by Gerd Pohlmann and Merata Mita, on a long-running industrial dispute over the building of the Māngere Bridge.

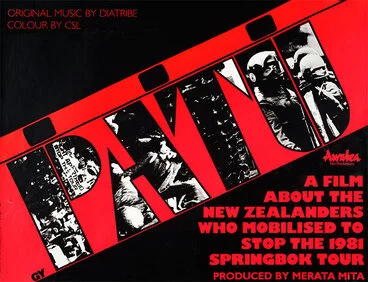

One of the most significant documentaries of the 1980s was the feature-length Patu! (1983), on the protests against the 1981 rugby tour of New Zealand by apartheid South Africa’s Springbok rugby team. Directed by Merata Mita with input from a large number of New Zealand’s film-makers, Patu! was an important counter to the government’s version of events and was the first feature-length New Zealand documentary directed by a woman.

Source: Documentary film - From the 1980s to 2000, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

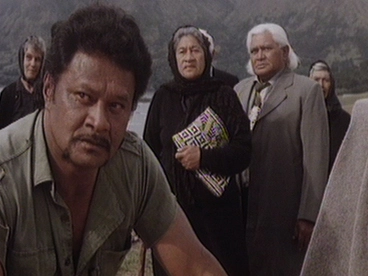

There was an explosion of film-making in the 1980s and more than 50 films were produced. Women directors, including Melanie Read and Gaylene Preston, challenged the male domination of the industry. Merata Mita’s Mauri (1988) was the first feature directed and written by a Māori woman, and the first from an entirely Māori perspective.

Source: Feature film, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Mauri

NZ On Screen

Mana waka (1990), directed by Merata Mita, told the story of war canoes (waka taua) built to celebrate the 1940 centennial of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, and screened in 1996 to celebrate the centenary of cinema. It used footage shot by Pākehā film-maker Jim Manley in the 1930s. Support came from the New Zealand Film Archive (now Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision), Manley’s descendants and the Māori queen, Dame Te Atairangikaahu.

Source: Documentary film - From the 1980s to 2000, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Mana Waka

Radio New Zealand

Koha - Nga Pikitia Māori

NZ On Screen

MERATA MITA (NGĀTI PIKIAO, NGĀI TE RANGI)

MERATA MITA

Our Wāhine

Patu!, 1983

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Merata — a son's tribute | E-Tangata

E-Tangata

RAMAI HAYWARD (NGĀTI KAHUNGUNU, NGĀI TAHU)

Ramai Hayward was a pioneering documentary and feature film-maker. She trained as a photographer in the mid-1930s and had established her own studio in Auckland when she starred in Rudall Hayward’s landmark film Rewi’s last stand (1940). This was the beginning of a 34-year film-making partnership with Hayward. Ramai was the driving force behind a series of educational films in the 1950s and 1960s, and one of the first western film-makers to visit Communist China. Some of her films explored Māori society and highlighted discrimination against Māori. As a Māori woman, she was a doubly unique figure in an industry dominated by Pākehā men.

Source: Hayward, Ramai Rongomaitara, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Ramai Hayward, 1969

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Ramai Hayward on the making of Rewi’s Last Stand

Radio New Zealand

Koha - Ramai Hayward

NZ On Screen

WI KUKI KAA (NGATI POROU, NGATI KAHUNGUNU)

Turangawaewae / A Place to Stand

NZ On Screen

Little Things

NZ On Screen

Wi Kuki Kaa in 'The Governor' TV series

Upper Hutt City Library

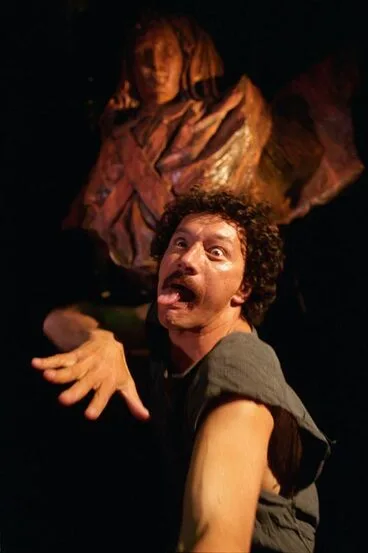

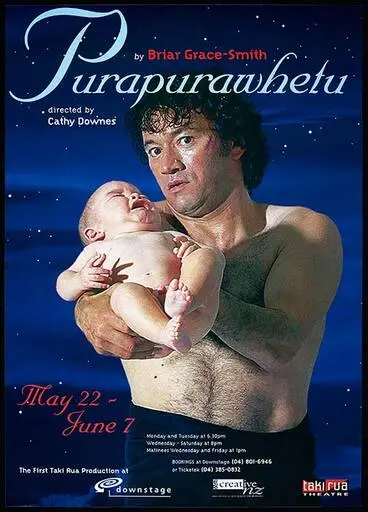

JIM MORIARTY (NGĀTI TOA, NGĀTI KOATA, NGĀTI KANUNGUNU)

Jim Moriarty, 1994

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Poster for Purapurawhetu, 1997

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

TAINUI STEPHENS (TE RARAWA)

Tainui Stephens

Radio New Zealand

Tainui Stephens: prominent Māori broadcaster...

NZ On Screen

DON SELWYN (NGĀTI KURI, TE AUPOURI)

Actor, Don Selwyn, brandishes Te Rauparaha's sword

Alexander Turnbull Library

RAWIRI PARATENE (NGĀ PUHI)

Rawiri Paratene on weaving his stage magic in Te Reo Māori

Radio New Zealand

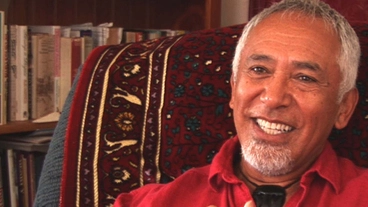

GEORGE WINIATA HENARE (NGĀTI POROU, NGĀTI HINE)

George Henare: acting on screen and stage...

NZ On Screen

Portrait of George Henare

The Arts House Trust

George Henare

Radio New Zealand

NANCY BRUNNING (NGĀTI RAUKAWA, NGĀI TUHOE)

Nancy Brunning: nurse Jaki Manu and beyond...

NZ On Screen

Nancy Brunning, a performer in the Downstage Theatre production of Waiora

Alexander Turnbull Library

Hikoi - Nancy Brunning

Radio New Zealand

ANZAC WALLACE (NGĀ PUHI)

Utu star Anzac Wallace's powerful legacy

Radio New Zealand

Children of the Dog Star - Power Stop

NZ On Screen

Anzac Wallace: Actor, community activist, leader

Radio New Zealand

TEMUERA MORRISON (TE ARAWA, NGĀTI WHAKAUE, NGĀTI MANIAPOTO, NGĀTI RARUA)

Production still showing Beth and Jake Heke singing at a party

Alexander Turnbull Library

Temuera Morrison: from Rotovegas to Hollywood...

NZ On Screen

Mahana interview: Temuera Morrison and Akuhata Keefe

Radio New Zealand

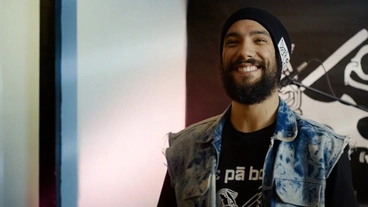

HIMIONA GRACE (NGĀTI TOA, NGĀTI RAUKAWA)

The Pā Boys

NZ On Screen

Members of the Maori drama group, Te Ohu Whakaari, in Wellington - Photograph taken by Stuart Ramson

Alexander Turnbull Library

Kaupapa Maori Film Making with Himiona Grace

Radio New Zealand

RENA OWEN (NGĀTI HINE, NGĀ PUHI)

RANGIMOANA TAYLOR (TE WHĀNAU-Ā-APANUI, NGĀTI POROU, TARANAKI)

Rangimoana Taylor

Radio New Zealand

PAORA TE OTI TAKARANGI JOSEPH (ATIHAU-A-PAPAARANGI, NGA RAURU)

Tātarakihi - The Children of Parihaka

NZ On Screen

Te Awa Tupua - Voices from the River

NZ On Screen

Māui's Hook

NZ On Screen

RACHEL TE AO MAARAMA HOUSE (NGĀI TAHU, NGĀTI MUTUNGA)

Rachel House

Radio New Zealand

A few beers with Rachel House

The Spinoff

CLIFF CURTIS (TE ARAWA, NGĀTI HAUITI)

Lee Tamahori directing Cliff Curtis in Once Were Warriors bar scene, Auckland

Alexander Turnbull Library

Cliff Curtis, 2006

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

BRIAR GRACE SMITH (NGĀ PUHI, NGĀTI WAI)

Cousins

NZ On Screen

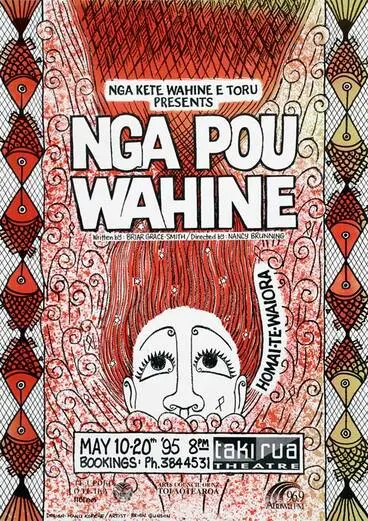

Taki Rua productions: Nga pou wahine

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

AINSLEY GARDINER (TE WHĀNAU-Ā-APANUI, NGĀTI PIKIAO, NGĀTI AWA)

Ainsley Gardiner

Radio New Zealand

Ainsley Gardiner: From Kombi Nation to Boy...

NZ On Screen

LEE TAMAHORI (NGĀTI POROU)

Once were warriors director Lee Tamahori posing by train

Alexander Turnbull Library

Lee Tamahori. 3 February, 2006.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Lee Tamahori: Making 'Mahana'

Radio New Zealand

TAIKA WATITI (TE-WHĀNAU-Ā-APANUI)

Hautoa Mā! The Rise of Māori Cinema

NZ On Screen

Taika Waititi makes Time's most influential list

Radio New Zealand

CHELSEA WINSTANLEY (NGĀTI RANGINUI, NGĀI TE RANGI)

Cultured Conversations with Chelsea Winstanley

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

Chelsea Winstanley: Whose lens is it anyway?

The Spinoff

KEISHA CASTLE HUGHES

JAMES ROLLESTON (NGĀI TE RANGI, TE ARAWA, NGĀTI POROU, WHAKATŌHEA)

The return of James Rolleston

Radio New Zealand

JULIAN DENNISON (NGĀTI HAUĀ)

Hunt for the Wilderpeople film poster

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Julian, Christian and Mabelle Dennison: filming Wilderpeople

Radio New Zealand

CIAN ELYSE WHITE (TE ARAWA)

Daddy's Girl (Kōtiro) wins Show Me Shorts Film Festival

Radio New Zealand

The first Maori Miss New Zealand inspires a new play

Radio New Zealand

This story was curated and compiled by Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, November 2020.