1975 Hīkoi (Māori Land March)

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library Services to Schools

On 14 September 1975, Dame Whina Cooper and a group of Māori protesters set off on a long march (hīkoi) to Wellington. This story covers the reasons for the march, the hikoi itself, and what it achieved for Māori.

Our whenua is our tūrangawaewae, our place to stand. It connects us to our whānau, our ancestors and to our future generations.

Whatungarongaro te tangata toitū te whenua

As man disappears from sight, the land remains

Source: Tupu.nz

BACKGROUND

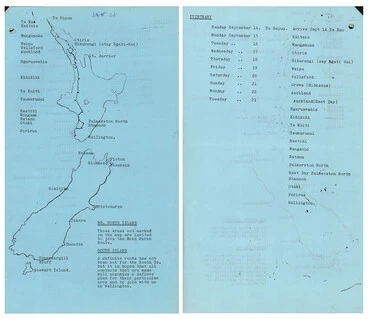

The 1975 Māori Land March (hīkoi) started at Te Hāpua in the far North Island and ended in Parliament grounds in Wellington. It took over 30 days and became a national event. The hīkoi slogan was 'not one more acre of Māori land' - a message of protest designed to draw attention to the continuing loss and confiscation of whenua (land) since 1900.

To fully understand the significance and the reason for the 1975 hīkoi, it is essential to step back and consider the cultural significance of whenua for Māori, early colonial land ownership legislation, the New Zealand Wars, and prior protests as precursors to this significant protest event.

This story of the 1975 land hikoi contains the following:

- Māori connection to land

- Land sales and land confiscation

- The Land wars

- Parihaka – the peaceful protest against land confiscation

- The Māori land march of 1975 – from Te Hāpua to Wellington

- Dame Whina Cooper leads the way – 14 September 1975

- The supporters

- The Petition – a Memorial Right

- The Hīkoi reaches Wellington – 13 October 1975

- Tent city in Wellington

- What was achieved

- Other significant land protests

- Quick facts

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Supporting resources

- Teaching and learning resources

- A gallery of images reflecting the many places, faces and times of the hīkoi

MĀORI CONNECTION TO LAND

In Māori culture, humans are seen as deeply connected to the land and to the natural world. Kaitiakitanga grows out of this connection and expresses it in a modern context.

Tangata whenua

Tangata whenua – literally, people of the land – are a group who have authority in a particular place, because of their ancestors’ relationship to it. Humans and the land are seen as one, and people are not superior to nature. The natural world is able to ‘speak’ to humans and give them knowledge and understanding. Human life is about aligning oneself with the natural world.

Source: Connected to nature – Kaitiakitanga – guardianship and conservation, Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

For more information:

- Hauora: Whenua - connection to the land – Whenua and its relationship to physical, mental, social and spiritual wellbeing.

Manaia mountain

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

LAND SALES AND LAND CONFISCATION

Early legislation focused on encouraging European settlement and individualising Māori land titles, replacing customary communal ownership. The trend towards individual ownership created problems for retaining Māori land. By 1891, Māori had virtually no land in the South Island and less than 40% of the North Island. Much of the land still held by Māori was poor quality and hard to develop.

Native Lands Act 1862 —The Act created the Native Land Court (renamed the Māori Land Court in 1947) to identify ownership interests in Māori land and to create individual titles in place of customary communal ownership. This change made sales of Māori land easier and saw the beginning of fragmented ownership interests in Māori land. The Act also allowed for up to 5% of Crown-granted Māori land to be taken for public works without compensation.

Native Lands Act 1865 — This Act replaced the 1862 Act and reflected a stronger push toward individualising Māori land title and fragmented ownership. For example, certificates of title could be issued to no more than 10 owners. The Act also expanded the ability to take 5% of Crown-granted Māori land for public works without compensation to include all Māori-owned land.

Native Land Act 1873 — Under this Act, title could no longer be held by iwi or hapū. All individuals with an ownership interest had to be named in the title. Individual Māori received blocks of land that were partitioned and repartitioned into uneconomic parcels of land. Fragmentation and loss of land continued.

Appendix: Summary of legislation about Māori land

Land confiscation law passed 3 December 1863

Parliament passed legislation enabling the confiscation (raupatu) of Māori land from tribes deemed to have ‘engaged in open rebellion against Her Majesty’s authority’. Pākehā settlers would occupy the confiscated land.

Under the New Zealand Settlements Act, Waikato lost almost all their land and Ngāti Hauā about a third of theirs.

Source: Land confiscation law passed — Events, New Zealand History.

The New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Native Land Court building, Ōnoke

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Native Land Court day, Ahipara

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

THE LAND WARS

Between the 1840s and the 1870s British and colonial forces fought to open up the interior of the North Island for settlement in conflicts that became known collectively as the New Zealand Wars. Sovereignty was contested on the ground despite the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, and Māori became less willing to sell land to the rapidly growing European population. Many Māori died defending their land; many other Māori allied themselves with the colonists for a variety of reasons, sometimes to settle old scores.

Most of the several thousand people killed during the New Zealand Wars were Māori, and the land of many of the survivors was subsequently confiscated.

Source: Introduction — New Zealand's 19th-century wars, New Zealand History.

For more information:

- The New Zealand Wars | Ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa from National Library of New Zealand Services to Schools.

‘The war council’

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

PARIHAKA — A PEACEFUL PROTEST AGAINST LAND CONFISCATION

About 1600 troops invaded the western Taranaki settlement of Parihaka, which had come to symbolise peaceful resistance to the confiscation of Māori land.

Source: Invasion of pacifist settlement at Parihaka 5 November 1881 — Events, New Zealand History.

For more information:

- Parihaka from National Library of New Zealand Services to Schools.

Children from Parihaka with Taare Waitara, Parihaka Pa

Alexander Turnbull Library

Parihaka, Mt Egmont and comet

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Parihaka

NZ On Screen

THE MĀORI LAND MARCH OF 1975 — FROM TE HĀPUA TO WELLINGTON

In early 1975, the idea of a ‘Māori Land March’ from Te Hāpua in the far north to Parliament was discussed. The aim would be to dramatise the entire package of Māori demands and aspirations which had yet to be addressed. The march would focus on the most iconic element of Māori losses and hopes: the land. Plans began to come together at a meeting of tribal representatives convened at Māngere Marae by the founding MWWL president (and National Party stalwart) Whina Cooper. In her address to the hui, Cooper implied that she was operating under the mantle of great Māori leaders such as James Carroll, Apirana Ngata and Peter Buck, all of whom she had known. She asserted customary Māori protocol through a ‘Memorial of Right’, thereby linking the march to a long tradition of earlier petitions to the Crown, especially those by Kings Tāwhiao and Te Rata in 1886 and 1914.

Maori and the State: Crown-Māori relations in New Zealand, 1950-2000, New Zealand Electronic Text Collection Te Pūhikotuhi o Aotearoa.

1975 land march

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Participants in the Māori Land March crossing Auckland Harbour Bridge

Alexander Turnbull Library

Māori land march, 1975

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

DAME WHINA COOPER LEADS THE WAY — 14 SEPTEMBER 1975

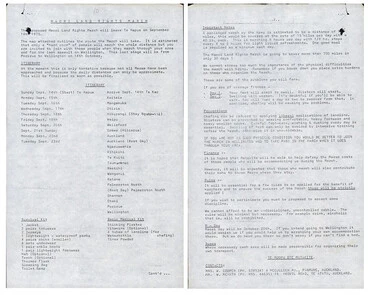

Fifty marchers left Te Hāpua in the far north on 14 September for the 1000-km walk to Wellington. Led by 79-year-old Cooper, the hīkoi quickly grew in strength. As it approached towns and cities, local people joined to offer moral and practical support. The marchers stopped overnight at different marae, on which Cooper led discussions about the purpose of the march.

Source: Whina Cooper leads land march to Parliament 13 October 1975 — Events, New Zealand History.

Whina Cooper and her moko

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

DAME WHINA COOPER

Our Wāhine

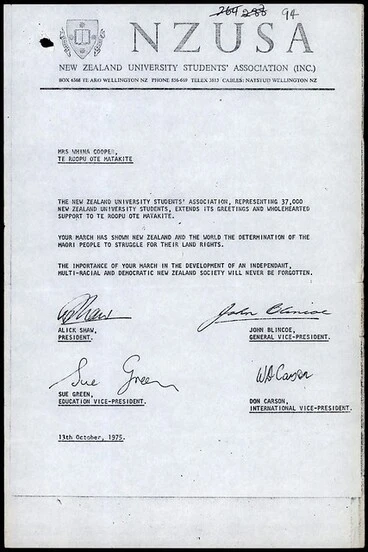

THE SUPPORTERS

Whina Cooper, the inaugural president of the Māori Women’s Welfare League, led Te Roopu o te Matakite, the group that organised the hīkoi. The march was similar to the Trail of Broken Treaties, a protest by Native American organisations in the US in 1972. Significantly, the march led to alliances between many Māori organisations, including the Kīngitanga, the New Zealand Māori Council, Ngā Tamatoa, the Māori Women’s Welfare League and other groups.

Source: Land protests — Ngā rōpū tautohetohe – Māori protest movements, Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Māori land march, 1975

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Te Rōpū Matakite o Aotearoa march to Parliament, 1975

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

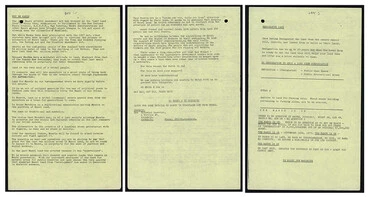

Māori Land March (1975) - Support from NZUSA

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Māori Land March (1975) - Route of March

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Māori Land March (1975) - Itinerary

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Māori land march, 1975

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

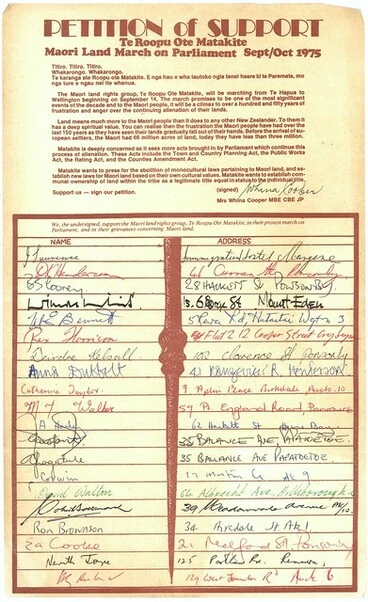

THE PETITION — A MEMORIAL RIGHT WITH around 60,000 SIGNATURES

They demanded, in the words of a key slogan, that ‘not one more acre of Maori land’ be alienated. As a leaflet entitled ‘Why We Protest’ explained: ‘Land is the very soul of a tribal people’. The leaflet linked the land with broader autonomist aspirations: ‘[We want] a just society allowing Maoris to preserve our own social and cultural identity in the last remnants of our tribal estate … The alternative is the creation of a landless brown proletariat with no dignity, no mana and no stake in society.’ While the focus was on Maori land and identity, some marchers also emphasised their solidarity with all working people: ‘We see no difference between the aspirations of Maori people and the desire of workers and their struggles.’

Maori and the State: Crown-Māori relations in New Zealand, 1950-2000, New Zealand Electronic Text Collection Te Pūhikotuhi o Aotearoa.

Māori Land March 1975 - Petition Sheet

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Māori Land March 1975 - Petition to Parliament

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Māori Land March (1975) - Why We March

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

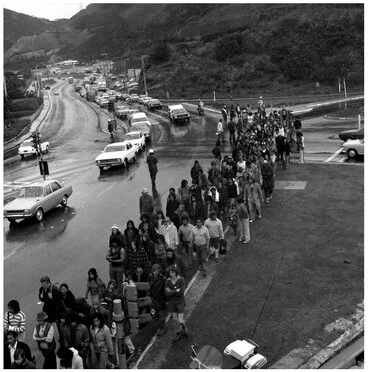

THE HĪKOI REACHES WELLINGTON — 13 OCTOBER 1975

The march reached Wellington on 13 October 1975. A memorial of rights signed by 60,000 people was prepared and presented to Prime Minister Bill Rowling, asking that all statutes that could alienate land be repealed and remaining tribal land be invested in Māori in perpetuity. Rowling promised that steps would be taken to address these concerns, but a group of protesters were not happy with his response. About 60 people set up a Māori embassy at Parliament and occupied the grounds.

Source: Land protests — Ngā rōpū tautohetohe – Māori protest movements, Te Are - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Te Matakite o Aotearoa - The Māori Land March

NZ On Screen

Māori Land March - 13 October 1975, Ngauranga Gorge, Wellington

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Photograph of Māori Land March demonstrators outside the Parliament Buildings in Wellington

Alexander Turnbull Library

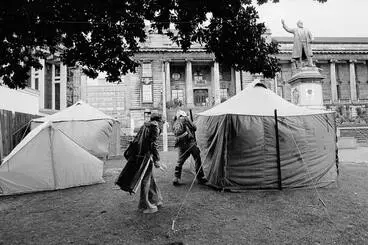

TENT CITY IN WELLINGTON

Following the 1975 land march Matakite broke into several factions. Whina Cooper publicly distanced herself from a group which established a tent embassy on the steps of Parliament. The march signalled the beginning of a renewed phase of Māori activism over land that was demonstrated by the occupations of Bastion Point (1977) and the Raglan golf course (1978).

Source: Tent embassy at Parliament, 1975 — Images and media, New Zealand History.

Tent embassy at Parliament, 1975

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Tents and belongings of Maori land marchers, Parliament Grounds, Wellington

Alexander Turnbull Library

Māori Land March (1975) - Ministry of Transport Correspondence

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

WHAT WAS ACHIEVED

The hīkoi and other developments surprised many Pākehā. They were used to hearing of New Zealand's so-called good race relations. Many now learned that Māori did not share this view. They also learned that the Treaty of Waitangi was more than a historical curiosity, and for Māori, it was the cornerstone of their relationship with the Crown.

Pākehā began to attend Treaty awareness workshops. Scholars challenged the accepted view of New Zealand's race relations history. By the 1980s books on the Treaty and related subjects appeared on best-seller lists. Some people disagreed, but increasing numbers of Pākehā supported Māori calls for the Treaty to be honoured.

In 1975 the Waitangi Tribunal was formed to investigate Māori grievances. It had the power to make findings of fact and recommendations, not binding decisions. The tribunal began hearings in 1977, but at first it could only investigate grievances that had occurred since 1975. In 1985 a law change allowed the tribunal to consider Māori grievances dating back to 1840. The hearing and settlement of historical claims would become a major focus of Māori energies, and some landmark settlements and decisions have been made.

Source: The Treaty in practice — Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand History.

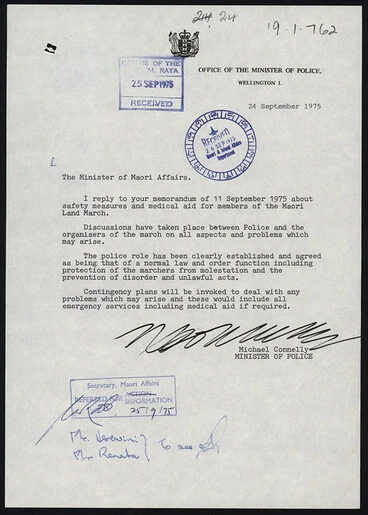

Māori Land March (1975) -Police Preparations

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

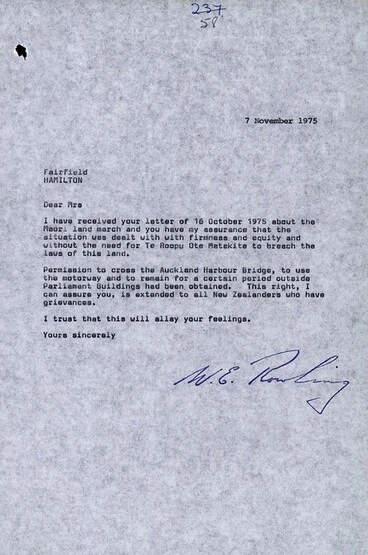

Māori Land March (1975) - Response to complaint by PM Bill Rowling

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Land Marchers camped at Ngati Poneke Marae, Wellington.

Alexander Turnbull Library

OTHER SIGNIFICANT LAND PROTESTS

Māori protested against land loss through petitions and occupations and by destroying survey pegs. Pan-tribal movements, including the Kīngitanga (Māori King movement) and Kotahitanga (Māori parliament movement), were often formed to advocate for Māori land issues. One movement in Hawke’s Bay, the Repudiation movement, was formed specifically to repudiate land sales that had taken place as inappropriate and unfair.

Bastion Point

In 1977–78 Joe Hawke led the Ōrākei Māori Action Group during their 506-day occupation of Bastion Point (Takaparawhā). This land, which had once been declared ‘absolutely inalienable’ by the Native Land Court, had over the years been taken from Ngāti Whātua.

Raglan golf course

The Raglan (Whāingaroa) protest raged in the 1970s over the Raglan golf course. The government had taken the land from Māori during the Second World War to use as a military airfield.

Pākaitore

From February to May 1995, Whanganui Māori occupied Pākaitore (also known as Moutoa Gardens), the site of the courthouse in Whanganui city, to protest lack of settlement of their treaty claims.

Ngāwhā and Te Kurī a Pāoa

In 2002 an occupation took place at Ngāwhā in Northland, where a new prison was to be built. For local iwi this site included wāhi tapu (sacred places) and the traditional lair of a taniwha (supernatural creature), Taukere.

Source: Land protests – Ngā rōpū tautohetohe – Māori protest movements, Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Foreshore and seabed hīkoi

Māori activists organised a hīkoi (march) in 2004 to protest against legislation that placed the seabed and foreshore in public ownership, overriding a Court of Appeal decision that the Māori Land Court could consider tribal claims to the foreshore and seabed.

Source: Parades and protest marches, Te Ara – The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand.

Ihumātao protest

In 2019 there were protests against Fletcher Building constructing a housing development on the 32ha land block at Ihumātao, South Auckland. Since 2016 the local Iwi activist group, Save Our Unique Landscape (SOUL) have occupied Ihumātao. SOUL want the land left undeveloped and also returned to the Iwi 160 years after confiscation by the Crown. Construction has been halted until the land dispute is resolved.

Bastion Point - The Untold Story

NZ On Screen

Foreshore and seabed protest, 2011

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Protest signs, Ihumatao Quarry Road, Māngere, 2017

Auckland Libraries

QUICK FACTS

- Dame Whina Cooper was the founding president of the Māori Women’s Welfare League and Te Rōpū Matakite (the group of visionaries).

- The distance travelled by the protesters between Te Hāpua in the Far North to Parliament in Wellington was around 1000 kilometres.

- The pouwhenua (land marker post) with the flag of the Te Rōpū o Te Matakite was always at the head of the 1975 Land March.

- Dame Whina Cooper made it clear that there was to be no banners and placards on the march.

- The 1975 Hīkoi was similar to the ‘Trail of Broken Treaties’ a cross-country protest held 3 years earlier by Native Americans who marched to Washington in the summer of 1972 to draw attention to Native grievances.

- The march left on 14 September, the first day Māori Language Week.

GLOSSARY

Definitions below have been taken from Te Aka and the Oxford Learner's Dictionary.

TE AKA

hapū– kinship group, clan, tribe, subtribe - section of a large kinship group and the primary political unit in traditional Māori society. It consisted of a number of whānau sharing descent from a common ancestor, usually being named after the ancestor, but sometimes from an important event in the group's history. A number of related hapū usually shared adjacent territories forming a looser tribal federation (iwi).

Kaitiakitanga – guardianship, stewardship, trusteeship, trustee.

Kīngitanga– a movement which developed in the 1850s, culminating in the anointing of Pōtatau Te Wherowhero as King. Established to stop the loss of land to the colonists, to maintain law and order, and to promote traditional values and culture. Strongest support comes from the Tainui tribes. Current leader is Tūheitia Paki.

iwi – extended kinship group, tribe, nation, people, nationality, race - often refers to a large group of people descended from a common ancestor and associated with a distinct territory.

OXFORD LERNER’S DICTIONARY

alienated – to make somebody feel that they do not belong in a particular group.

aligning – to change something slightly so that it is in the correct relationship to something else.

autonomist – (from autonomy) the ability to act and make decisions without being controlled by anyone else.

communal – involving different groups of people in a community.

confiscation – the act of officially taking something away from somebody, especially as a punishment.

convened – to come together for a formal meeting.

fragmented – broken into small pieces or parts, in a way that may have a negative effect.

grievances – something that you think is unfair and that you complain or protest about; a feeling that you have been badly treated.

partitioned – to divide something into parts.

perpetuity – for all time in the future.

proletariat – the class of ordinary people who earn money by working, especially those who do not own any property.

sovereignty – complete power to govern a country.

statutes – a law that is passed by a parliament, council, etc. and formally written down.

subsequently – afterwards; later; after something else has happened.

Māori land march passes through Awapuni

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Schoolchildren line roadside to watch Māori Land March pass, Northland

Alexander Turnbull Library

Tame Iti holding pou whenua, accompanied by Whina Cooper, leading Māori Land March along Hamilton street

Alexander Turnbull Library

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Use our lending service to order these books and other related topics associated with the land march.

Go Girl: A Storybook of Epic NZ Women by Barbara Else, 2018 (primary, intermediate).

Hīkoi: Forty Years of Māori Protest by Aroha Harris, 2004 (intermediate, secondary).

New Zealand's Top 100 History-Makers by Joseph Romanos, 2008 (primary, intermediate, secondary).

SUPPORTING RESOURCES

Heroines of the Hīkoi — a special video series from Newsroom profiling 7 wāhine who walked with Dame Whina Cooper in the 1975 Hīkoi. This one features Dame Whina's daughter, Hinerangi Cooper-Puru.

…it won’t be a lonely walk” – commemorates the 40th anniversary of the ‘Not One Acre More’ hikoi includes a poem written by Hone Tuwhare.

Te matakite Aotearoa / The Māori Land March – marchers and supporters such as Eva Rickard, Tama Poata, and Joe Hawke give reasons for their involvement.

The Māori Land March – from Maori and the State: Crown-Māori relations in New Zealand/Aotearoa, 1950-2000 from NZETC.

Māori Land March 1975 – This entry from Many Answers has links to reliable online resources on the 1975 Hīkoi.

1975 Māori Land March – a collection of images from Archives New Zealand.

1975 Matakite Maori Land March on Parliament Grounds – a video of protestors as they approach Parliament Grounds.

‘Not one more acre’ – its over 40 years since Dame Whina Cooper left with her mokopuna to march to Wellington to protest Māori land alienation.

A sacred mission to secure a future for Māori – has images of the route taken by the marchers and an image of the pouwhenua at Te Kōngahau Museum at Waitangi.

Stand Up: A History of Protest in New Zealand – article from the School Journal that covers a number of protests over social and historical issues in New Zealand including the 1975 Hīkoi.

Whina Cooper: fearless and unforgettable – Tainui Stevens is impressed by Whina Cooper’s charisma and korero when she meets her for the first time.

Whina Cooper – biography of Te Rarawa woman of mana, teacher, storekeeper and community leader.

TEACHING AND LEARNING RESOURCES

Hikoi (TMCC13) – View (or print) the curiosity card about hikoi. Use the card’s fertile questions to inspire inquiry. Follow the link for more resources to help with teaching and learning.

Resistance and conflict – has resources, contexts and videos from TKI to shape a resistance and conflict based programme of learning.

A GALLERY OF IMAGES REFLECTING THE MANY PLACES AND FACES OF THE HĪKOI

Lyn Doherty, Dave Clarke, and Vivian Hutchinson line up for kai

Alexander Turnbull Library

Stones for hangi to feed land marchers

Alexander Turnbull Library

Vivian Hutchinson, Turi Blake, and others reading a newspaper

Alexander Turnbull Library

Otoko women prepare food for Maori land marchers

Alexander Turnbull Library

Wahine sitting on grass at Whakapara picnic

Alexander Turnbull Library

Poet Hone Tuwhare writing in his notepad during a stop on the Māori Land March

Alexander Turnbull Library

Participants in Māori Land March at Ōtoko Pā

Alexander Turnbull Library

Washing on the line during a rest day at Te Kūiti Pā

Alexander Turnbull Library

Four Maori Land Marchers prepare for the third phase of the march

Alexander Turnbull Library

Tama Poata and Witi McMath leaning on a fence

Alexander Turnbull Library

Maori Land March. Ngauranga Gorge from overbridge

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Māori Land March participants at Takapūwāhia Marae, Porirua

Alexander Turnbull Library

Aftermath of the arrival of the Māori Land March into Wellington

Alexander Turnbull Library

Aftermath of the arrival of the Māori Land March into Wellington

Alexander Turnbull Library

Aftermath of the Land March at Parliament, and, two men clearing a drain

Alexander Turnbull Library

This story was curated and compiled by Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, November 2020.