The history of children and the welfare system in Aotearoa New Zealand

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library Services to Schools

This story covers a range of acts and changes by various governments to address social welfare issues for children in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Dental health van

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Early New Zealand governments wanted to improve child and maternal health as a way of promoting reproduction, stable communities and national population growth. In 1924 the League of Nations endorsed the Declaration of the Rights of the Child and urged governments to improve child welfare, maternal working conditions and income support programmes. The New Zealand Child Welfare Act 1925 established the Child Welfare Branch of the Education Department, which became responsible for orphaned, destitute, neglected and ‘out of control’ children.

Source: Family welfare — Welfare, work and families, 1918–1945, Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

1867 — NEGLECTED AND CRIMINAL CHILDREN ACT

In the late 19th century local governments were lobbied to control children who were not attending school and were defined as ‘out of control’. The Neglected and Criminal Children Act 1867 allowed provincial councils to administer the care and custody of children who were neglected or orphaned. Industrial and reformatory schools were developed for these children, and focused on encouraging work habits and Christian morals. These child protection laws, residential schools and welfare agencies challenged assumptions that parents and families had sole authority over children.

Source: Family welfare — Mothers and children – 1800s to 1917, Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

NEGLECTED CHILDREN. (Timaru Herald, 01 January 1878)

National Library of New Zealand

THE CASE OF THE BOYPATERSON. (North Otago Times, 17 April 1875)

National Library of New Zealand

RAGGED SCHOOL. (Daily Southern Cross, 20 May 1870)

National Library of New Zealand

1882 — INDUSTRIAL SCHOOLS ACT

In the 19th century, poor, neglected or deliquent children were sent to industrial schools, where they were educated and trained in vocational skills. In theory, delinquent children were supposed to be kept separate, but in practice the children were all schooled together. These girls are in the workroom at the Burnham Industrial School near Christchurch in 1874. They are working on handcrafts.

Source: Childhood — Industrial School, 1874, Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

View the Industrial Schools Act 1882.

Burnham Industrial School, about 1874

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Caversham Industrial School

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

CHILDREN COMMITTED TO INDUSTRIAL SCHOOLS. (Grey River Argus, 24 January 1889)

National Library of New Zealand

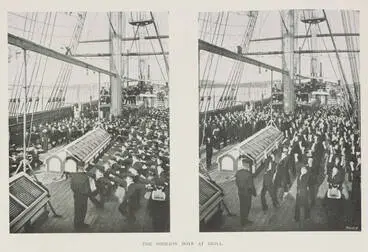

1899–1909 — REFORMATORIES FOR UNCONTROLLABLE CHILDREN AND CHILDREN WITH CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS

In the 19th century neglected, poor and delinquent children were sent to industrial schools where they were educated and trained in vocational skills. A combination of teaching and punishment was supposed to mould children into useful citizens. In 1900 separate reformatories were opened to accommodate delinquents.

Until 1906 children charged with criminal offences were tried in open courts alongside adults. After this magistrates could hear child cases (16 years and under) in closed courts. Children could be warned or put on probation rather than convicted. Industrial schools and reformatories were progressively closed or reorganised.

Source: Childhood — Child discipline and justice, Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

View the Reformatory Institutions Act 1909.

The Sobraon boys at drill

Auckland Libraries

Waikeria Prison

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

James Gillham

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

1908 — THE LEGITIMATION ACT

By the 1900s, the ‘problem’ of child illegitimacy was at the forefront of public debate. An article in The Press entitled ‘The Social Cancer’ provoked a flurry of letters to the editor reflecting on its causes and suggesting remedies. [1] While many thought that single mothers should not have things ‘too easy’, some expressed this view more strongly than others.

While assistance for mothers remained focused on punishment and reform, more interest began to be shown in the ‘innocent children’ whose illegitimacy resulted in hardship. [3] In the 1890s, alarm about the declining European birth rate saw illegitimate children begin to receive better care and attention. The motivation for the Infant Life Protection Act 1893, and its subsequent revisions, was the comparatively high mortality rate of illegitimate children. Revelations of neglect in private care captured public interest and aroused emotion.

Source: Helth and welfare — Crèches and early childcare, NZHistory.

The Legitimation Act 1908 gave children born before marriage the same entitlement and rights as a child born in wedlock.

Twombstones? 'Minnie Dean.' 2 February 2009.

Alexander Turnbull Library

The Nineties

NZ On Screen

INTERESTING WILL CASE. (Mataura Ensign 1-5-1907)

National Library of New Zealand

1925 — NEW ZEALAND CHILD WELFARE ACT

Early New Zealand governments wanted to improve child and maternal health as a way of promoting reproduction, stable communities and national population growth. In 1924 the League of Nations endorsed the Declaration of the Rights of the Child and urged governments to improve child welfare, maternal working conditions and income support programmes. The New Zealand Child Welfare Act 1925 established the Child Welfare Branch of the Education Department, which became responsible for orphaned, destitute, neglected and ‘out of control’ children.

Source: Family welfare — Welfare, work and families, 1918–1945, Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

View the Child Welfare Act 1925.

JUVENILE OFFENDERS (Evening Post, 12 October 1934)

National Library of New Zealand

CHILD OFFENDER (Evening Post, 14 September 1931)

National Library of New Zealand

THE POLICE AND THE CHILD (NZ Truth, 07 October 1926)

National Library of New Zealand

1993 — AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND RATIFIES THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD (CRC)

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)(external link) was adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989, and entered into force 2 September 1990. New Zealand ratified the CRC on 6 April 1993.

Demonstration, International Year of the Child

NZEI Te Riu Roa (New Zealand Educational Institute)

United Nations concerned over Kiwi kids' rights. 21 January 2011

Alexander Turnbull Library

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

1990s — CHILDCARE CENTRES ARE REGULATED BY THE GOVERNMENT AND RECEIVE SUBSIDISED FEES

Most early childhood education services are licensed – this means they have to fulfil certain requirements in staffing, curriculum and premises outlined in the Education Act 1989. Licensed centres receive more government funding than licence-exempt centres. All care and education services and kindergartens are licensed, as are most playcentres and kōhanga reo.

Source: Early childhood education and care — New developments, 1970s to 2000s, Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

View organisations concerned with early childhood care and education.

Stepping out in good cause, Māngere, 1990

Auckland Libraries

Dunedin crèche proposal, 1879

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

First anniversary of New Brighton crèche

Christchurch City Libraries

1 OCTOBER 1999 — DEPARTMENT OF CHILD, YOUTH AND FAMILY SERVICES (CYFS) ESTABLISHED

In 1999 the Department of Child, Youth and Family Services (CYFS) replaced the Children, Young Persons and Their Families Agency as the government agency responsible for child protection and children who broke the law or were at risk of offending. CYFS collaborated with police, the courts and other social welfare organisations.

Source: Childhood — Children’s rights and well-being, Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Tremain, Garrick, 1941- :CYFS. 9 April 2015

Alexander Turnbull Library

Murdoch, Sharon Gay, 1960- :Ms Rebstock and the CYF business case. 4 April 2015

Alexander Turnbull Library

2014 — THE CHILDREN'S ACT

The Children's Act 2014 was part of a series of comprehensive measures brought in to protect and improve the wellbeing of vulnerable children.

Oranga Tamariki Ministry for Children

View the Children's Act 2014.

Launching a public discussion document

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Social workers

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Evans, Malcolm Paul, 1945- :New child protection laws. 13 August 2013

Alexander Turnbull Library

1 APRIL 2017 — MINISTRY FOR VULNERABLE CHILDREN, ORANGA TAMARIKI REPLACES CHILD YOUTH AND FAMILY SERVICES

Child, Youth and Family (CYF) became New Zealand’s statutory child-welfare agency in 1999. CYF was replaced by the Ministry for Vulnerable Children (Oranga Tamariki) in April 2017 after an expert group produced a critical review of CYF services in December 2015. The agency was renamed Oranga Tamariki – Ministry for Children on 31 October 2017. Oranga Tamariki social workers handle notifications about suspected child abuse and neglect. They assist families having difficulties caring for their children and make alternative care arrangements if children are not safe in the home environment.

Source: Child abuse — State action on child abuse, Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

View the website of Oranga Tamariki Ministry for Children.

Whānau share stories of Oranga Tamariki experiences

Radio New Zealand

Dalton House Napier 2020

Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank

2018 — CHILD POVERTY REDUCTION BILL

Children’s well-being has been identified as strongly related to the financial circumstances of the households in which they grow up. Groups such as the Child Poverty Action Group have campaigned for increased attention to the impacts on children of poverty and the need to monitor levels of poverty among children. They have estimated that 14% of children in New Zealand are living in material hardship and 8% in severe material hardship. The Child Poverty Monitor has been documenting material hardship in households that include children. The impacts of child poverty include higher levels of infant deaths, higher rates of respiratory and communicable diseases, higher rates of hospitalisation, lower housing quality and lower rates of educational attainment.

The Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018 made governments responsible for meeting targets to reduce child poverty and address child well-being. The legislation received cross-party support.

Source: Childhood — Children’s rights and well-being, Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

View the Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018.

Govt unveils details of child poverty targets

Radio New Zealand

Child Poverty Action Group protest

Alexander Turnbull Library

For more on the children and the welfare system in Aotearoa New Zealand:

This story was curated and compiled by Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa | National Library of New Zealand, Services to Schools staff, April 2022.