Tangiwai Railway Disaster, Christmas Eve 1953

A DigitalNZ Story by Zokoroa

On Christmas Eve 1953, a passenger train derailed off the Tangiwai Bridge into the flooded river south of Mt. Ruapehu. Of the 285 aboard, only 134 survived, and our nation was plunged into mourning. What happened before, during and afterwards?

Tangiwai, Disaster, National disasters, Trains, Railways, Ruapehu, Volcanoes, Memorial, Christmas, Railway disaster

A poignant moment was hearing for the first time about the Tangiwai railway disaster - that on Christmas Eve 1953, the passenger express train travelling from Wellington to Auckland had derailed off the Tangiwai Bridge into the flooded Whangaehu River, 10 km west of Waiōuru in the central North Island. Of the 285 passengers and crew on board, 134 survived and 151 died, with most drowned in the floodwaters.

The rail tragedy plunged our nation in mourning and made headlines around the world. The timing of the accident, with those aboard travelling with Christmas presents and those waiting to greet them at stations and at home unaware of what had happened, added to the sense of tragedy. It affected people in various ways - many either knew of someone who was involved in the tragedy or knew of someone who had changed their plans to travel that evening on the train. Tributes arrived from overseas, and a memorial service was also held in London's Westminster Abbey for New Zealanders, relatives and friends. Just off the main highway between Ohakune and Waiōuru, you can view the Tangiwai National Memorial site. The place name Tangiwai means ‘weeping waters’ in Māori.

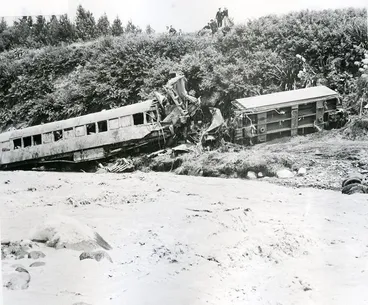

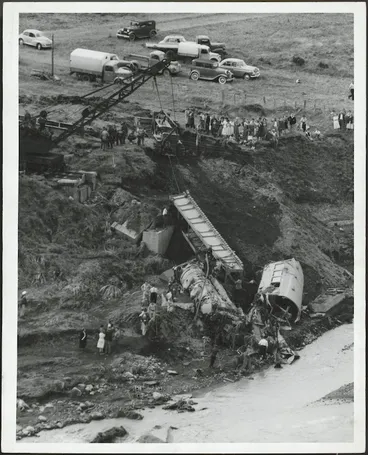

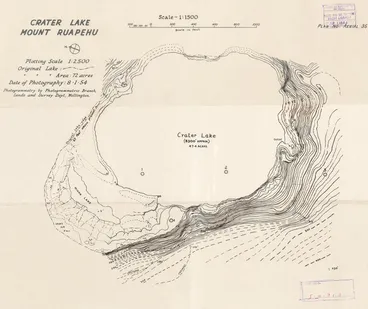

Floodwaters from Mt Ruapehu's Crater Lake had damaged the Tangiwai Bridge.

The lahar of water, sand & boulders had damaged 4 of the 8 piers & dislodged 5 of the 7 spans of the 198 ft long bridge.

Alexander Turnbull Library

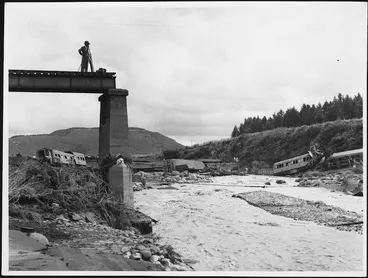

The locomotive engine plunged into the river, taking first 5 of 9 carriages with it. The sixth carriage then followed.

The last 3 carriages & the guard's van & postal van stayed on the remaining portion of the bridge.

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Of 285 passengers & crew on board, 134 survived & 151 died.

Most were drowned in the floodwaters & 20 bodies not recovered were possibly swept out to sea.

Palmerston North City Library

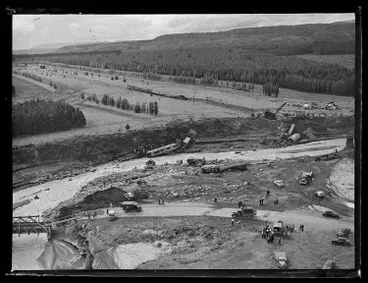

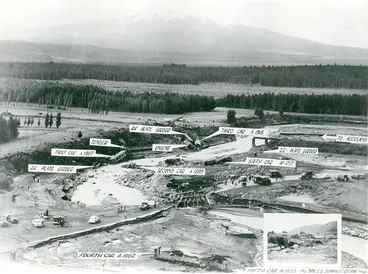

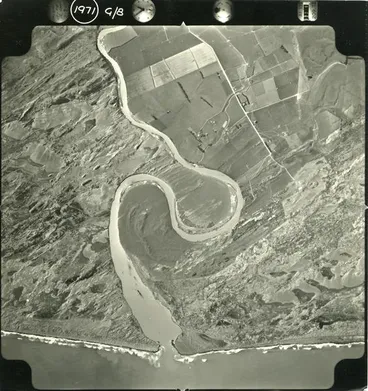

An aerial view of the bridge and wrecked carriages.

Auckland Libraries

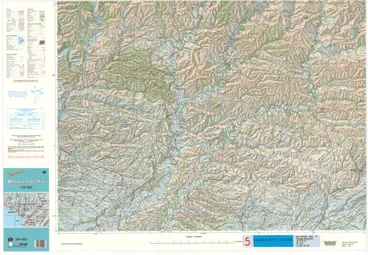

Map shows location of the locomotive & the six of the nine carriages that fell from the bridge.

The fifth carriage was swept 1.5 miles downstream.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

1. What happened on Christmas eve, 1953?

The following timeline is provided in the official report: Tangiwai Railway Disaster: Report of the Board of Inquiry (RE Owen. 30 April 1954).

3pm: Train left Wellington for Auckland

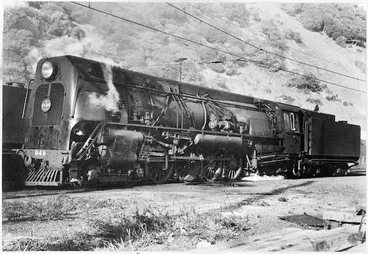

At 3pm, the express train had left Wellington for Auckland on Christmas Eve 1953. The locomotive Ka 949 had nine carriages (five second-class and four first-class carriages), a guard's van and a postal van. The length of the train was 704 ft. approx and its weight, 467.3 tons.

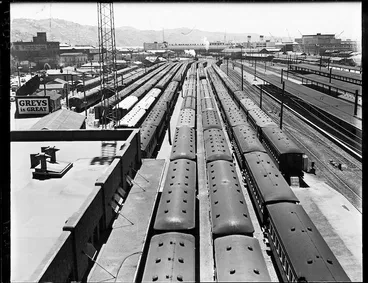

At 3pm on Christmas Eve 1953, the express train left Wellington Station to travel overnight to Auckland

Alexander Turnbull Library

The Ka 949, a K class locomotive, had 9 carriages and 2 vans

Alexander Turnbull Library

Train's length was 704 ft approx & its weight 467.3 tons

Alexander Turnbull Library

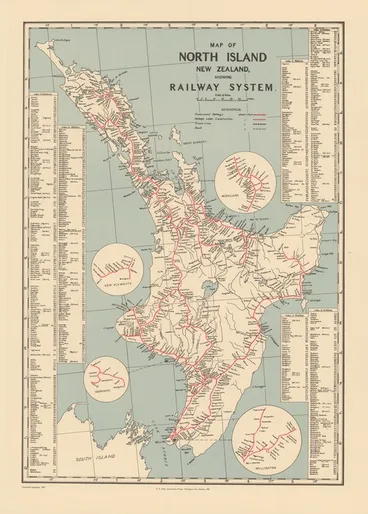

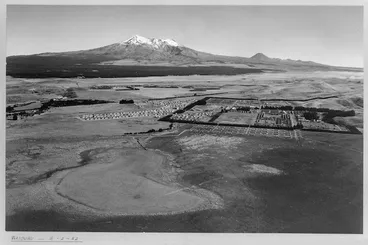

The train travelled to Auckland via the Waiōuru and Tangiwai Rail Stations, which are to the south of Mt. Ruapehu. After the train left the Waiōuru Station, there were 285 people on board, including five crew - Engine Driver, Fireman, Guard, Assistant Guard, and Car Attendant - and two postal officials travelling in the postal van at the rear of the train.

The train travelled to Auckland via the Waiōuru & Tangiway Rail Stations, south of Mt. Ruapehu

National Library of New Zealand

People on board were travelling for Christmas and many hoped to see Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip in Auckland - the first visit of a reigning monarch to New Zealand. The Royal couple had arrived in Auckland on 23 December for a Royal tour of the North and South Islands until 30 January 1954.

People on board were travelling for Christmas and had presents for family and friends

Auckland Libraries

8.02pm: Mt. Ruapehu's Crater Lake bursts

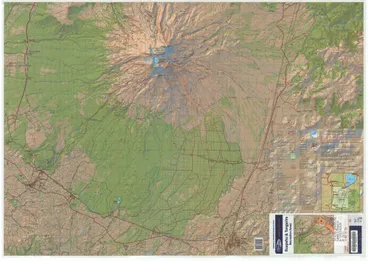

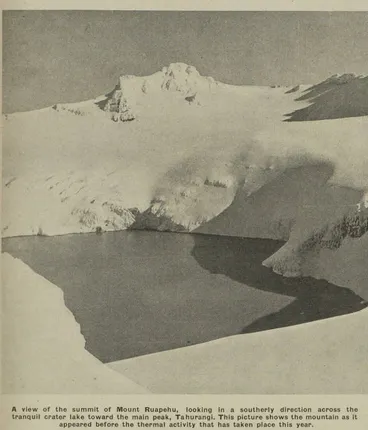

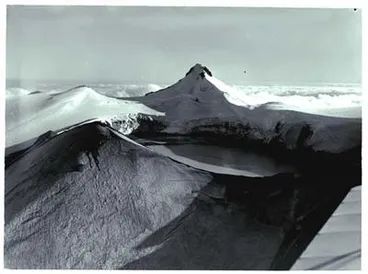

About five hours after the train left Wellington, the rim of Mount Ruapehu’s Crater Lake (Te Wai ā-moe) had given way at 8.02 pm, releasing about 340,000 cubic metres of water. Mt Ruapehu's Crater Lake sits between its three peaks - Tahurangi (2,797 m), Te Heuheu (2,755 m) and Paretetaitonga (2,751 m). The Lake's outlet is at the head of the Whangaehu Valley, where the Whangaehu River arises. An eruption in 1945 formed a tephra dam, behind which the Lake grew in volume.

Mt Ruapehu lies north of Ohakune & the railway stations at Waiōuru & Tangiwai

Auckland Libraries

Mt Ruapehu's Crater Lake sits between its three peaks

Tahurangi (2,797 m), Te Heuheu (2,755 m) & Paretetaitonga (2,751 m)

Alexander Turnbull Library

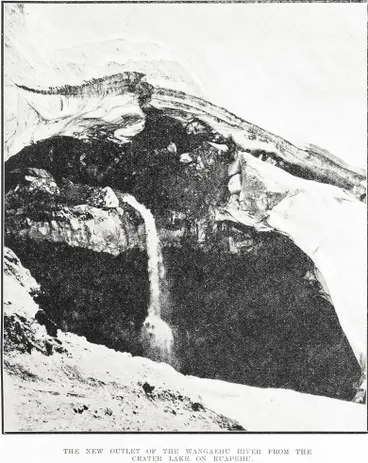

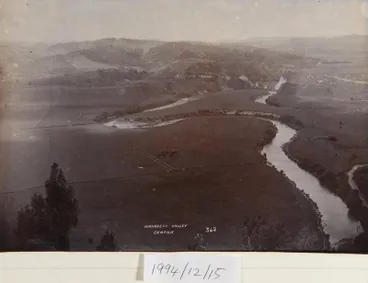

The Crater Lake's outlet is at the head of the Whangaehu Valley, where the Whangaehu River arises

Tauranga City Libraries

An eruption in 1945 formed a tephra dam, behind which the Crater Lake grew in volume

Crater (c.300 metres deep) slowly filled with water after the eruption. By 1953, Lake was 8m higher than before 1945.

Auckland Libraries

What caused the avalanche of water?

The Board of Inquiry (Ibid, pp. 6-7) reported that the Crater Lake would discharge water through a small cave which flowed down through the riverlets to the Whangaehu River. However, subsequent investigations showed that water must have also been seeping through the volcanic ash and scoria alongside the small cave, to form another channel beneath the ice at a lower level. Outcrops of volcanic rock to the right of the small cave had collapsed and formed another huge cave about 150 ft. wide and about 100 ft. high at the entrance. A stream began flowing from the Crater Lake beneath a pile of fallen ice into the new cave.

By 1953, Crater Lake was 8m higher than its level before 1945 (300m)

Auckland Libraries

Crater Lake would discharge water through a small cave which flowed down through riverlets to the Whangaehu River

However, water must have also seeped through the volcanic ash & scoria alongside the small cave to form another channel.

Auckland Libraries

Outcrops of volcanic rock to right of the small cave collapsed & formed another huge cave, c.150 ft. wide & 100ft high

A stream began flowing from the Crater Lake beneath a pile of fallen ice into the new cave.

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

Erosion in volcanic Ash barrier & cracks in ice:

Erosion in the new channel may have reduced the strength of the volcanic ash barrier between the old cave and the new cave. As small crevasses were created in the ice above the new cave, the ash barrier alongside of the existing cave made cracking movements and suddenly collapsed about 8 pm. This lead to the rush of water commencing two or three minutes after 8 pm down the channel under the ice to the Whangaehu River.

On 24 Dec 1953 at 8pm, the ash barrier between the 2 caves collapsed, releasing torrent of water

As small crevasses were created in ice above the new cave, cracking movements made the ash barrier collapse.

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

The rush of water commenced 2 or 3 minutes after 8 pm down the channel under the ice to the Whangaehu River

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

No earthquake recorded on seismograph:

Another explanation for the collapse of the ash barrier was also explored - the possibility of an earthquake having occurred. However, "Mr G. Eiby, of the Seismological Observatory, reported that the seismograph at the Chateau did not record any earthquake or volcanic disturbance, but it recorded vibration, presumably caused by the rush of water, commencing two or three minutes after 8 p.m. on 24 December 1953. " (Ibid, p.7)

Mr G. Eiby, of Seismological Observatory, reported the seismograph at the Chateau did not record any earthquake

But it recorded vibration, presumably caused by the rush of water, commencing 2 or 3 mins after 8 pm

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Size of the flood:

Charles William Oakey Turner, Engineer-in- Chief, Ministry of Works, gave the following account:

"A Senior Engineer of the Works Department's] report indicated that the lake fell by approximately 20 ft. in 150 minutes. During the discharge of the first 20 ft. it is believed the flow varied from an initial maximum of about 30,000 cu. ft. per second to about 1,300 cu. ft. per second. The remaining 6 ft. then discharged comparatively slowly. The very high discharge rate adequately explains the erosion of the mountainside and the great volume of silt and boulder-laden water concentrated at the bridge site." (Ibid, p.9)

Flood TRAVELLED c.25 miles ALONG WHANGAEHU RIVER:

The avalanche of water travelled approximately twenty-five miles at an average speed of ten miles per hour to reach Tangiwai:

"...[A]bove Tangiwai the Whangaehu River has three main tributaries, the Wahianoa, Makahikatoa, and Whangaehu itself. The Whangaehu proper flows down the mountain side from the Crater Lake for approximately eight and one-half miles in an easterly direction, then turns abruptly to the south at the bottom of a fan, runs more or less parallel with the Desert Road for approximately six miles, thence in a south-westerly direction towards Tangiwai. The total distance to Tangiwai is approximately twenty-five miles." (ibid, p.8)

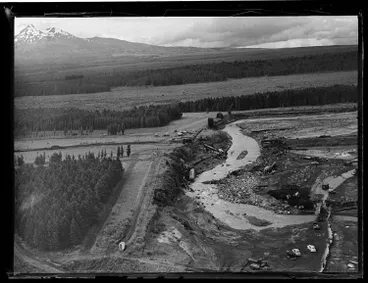

Flood swept from Ruapehu onto the boulder fan & spread across all the watercourses down to the Whangaehu River

Te Whare o Rehua Sarjeant Gallery

The River flows down Crater Lake for 8.5 miles to east, then turns south & runs parallel with Desert Road for 6 miles

Then it then flows south-westerly to Tangiwai for c.10.5 miles

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The total distance from the Crater Lake to Tangiwai is approximately twenty-five miles

Tauranga City Libraries

10.10-10.15PM: Lahar of water, sand & Boulders hits Tangiwai Rail Bridge's pylons, carrying away PIER 4

The Board of Inquiry (Ibid, pp. 8, 10) described what happened next:

The lahar reached Tangiwai about 10.10-10.15 p.m. in the form of a dense wave of water, sand, and boulders. While the lahar passed there seems to have been little or no erosion, and the shingle flat in which the river flows was smothered with a swiftly moving mass of sediment. Above the railway bridge the flood spread out across the flats, depositing sand and boulders, and reached a depth of 20 ft. at the bridge. It piled up to cross the highway and highway bridge, depositing sand and flooding across the highway for several hundred yards, and swept on down the river. Along the banks the vegetation was quickly buried by sand, but on the bed of the channel vegetation was flattened and abraded...." (p.8)

"A flood rise of 15 ft. to 17 ft. has been measured at the railway bridge (i.e., above the bed as after flood) and slope area measurements give a mean discharge of approximately 23,000 cusecs. This agrees with the general opinion that the peak discharge was approximately 30,000 cusecs." (p.10)

At 10.10pm-10.15pm: The wave of water, ice, mud & rocks hit Tangiwai Rail Bridge's concrete pylons & carried away Pier 4

A flood rise of 15 - 17 feet was measured at the railway bridge, with a maximum flow of 30,000 cu. ft. per second.

Auckland Libraries

10.09pm: Train left the Waiōuru railway station

The train left the Waiōuru railway station at 10.09 pm

Auckland Libraries

10.20pm: Train left the Tangiwai Rail Station

The Tangiwai Rail Station is situated approximately one mile (1.6 kilometres) from the Tangiwai railway bridge over the Whangaehu River. It is a flag station staffed by Station Agents - trains stop only when a flag or other signal is displayed or when passengers are to exit the train.

The Station Agent reported that the train passed through the Tangiwai Railway Station on time at 10.20 pm. The train's speed was "approximately 40 miles per hour" and as "going slower than usual". The engine headlight was on, some carriages were still lighted, as also were the tail and side lights on the last vehicle of the train.

At 10.20pm, train left the Tangiwai Station, which is about one mile from the Tangiwai Bridge, & was travelling 40mph

Auckland Libraries

10.21pm: Train reaches the Tangiwai Bridge (known as Bridge No. 136)

The lahar from Mount Ruapehu had removed the fourth pier a few minutes before the train started to cross the bridge. When the train reached the weakened bridge at 10.21 p.m, the bridge buckled beneath its weight. Earlier, a mixed goods train had crossed the river about 7pm (just over three hours before the express train), and the river had appeared normal then.

Engine driver applied brakes:

Cyril Ellis, who was the postmaster from Taihape, had been forced to stop his car when he reached the road bridge, which was submerged. When he saw the light of the approaching locomotive he ran towards it waving a torch in an attempt to warn the driver. (Source: Search and rescue', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/responding-to-tragedy/tangiwai-1953, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 6-Jan-2014)

Later investigations by the Board of Inquiry (op cit, p.5) concluded: " It seems clear that either that action [by Ellis] or the observation by the locomotive crew in the headlight beam of the condition of the bridge and river caused the driver to make an emergency application of the brakes. They were applied some distance before reaching the bridge, but in insufficient time to prevent the disaster. Subsequent examination revealed that the fuel-oil supply tap was turned off, and its peculiar construction makes its clear this was done by the fireman." This was unable to be confirmed as the engine driver Charles Parker and fireman Lancelot Redman were amongst those who lost their lives.

At 10.21pm, the train reached the bridge

Train driver Charles Parker applied brakes & fireman Lancelot Redman turned off the fuel supply

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Locomotive engine & first 5 carriages plunged into river:

The applying of the brakes was too late to prevent the locomotive and its tender plunging into the swollen river, taking the first five carriages (which were the second class carriages) with it.

The locomotive engine plunged into the river, taking first five carriages with it

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Locomotive on the banks of the Whangaehu Stream, at the scene of the 1953 railway disaster at Tangiwai

Alexander Turnbull Library

Tangiwai Disaster 1953

Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank

Banks of the Whangaehu Stream at the scene of the railway disaster at Tangiwai

Alexander Turnbull Library

Sixth carriage (CAR Z) then toppled into the water:

The sixth carriage (Car Z), which the first of the four first-class carriages, dangled over the edge of the bridge at a 45-degree angle, and after a short period of time, also fell into the torrent. The three remaining first-class carriages, and the guard's van and postal van were left standing on the remaining portion of the bridge with the lights still on.

Sixth carriage (Car Z) then toppled, leaving 3 remaining first-class carriages & guard's van & postal van on the bridge

Auckland Libraries

2A. First on the scene RESCUEr stories

Car Z carriage:

When Car Z teetered on the edge of the bridge, Cyril Ellis (the passing motorist) and William Inglis (the train’s guard), climbed in to warn the passengers and move them to the carriage behind. But Car Z broke free from the remaining three carriages and toppled into the river. It rolled downstream before coming to rest on a bank. Ellis, Inglis and one of the passengers, John Holman, managed to get all but one of the 22 passengers out through the broken windows and onto the side of the carriage. After waiting on the carriage for over an hour until the floodwaters receded, the men then formed a human chain in waist-deep water, helping everyone to make their way to the bank.

On the last day of the royal tour the Queen awarded Cyril Ellis and John Holman the George Medal for their services at Tangiwai. William Inglis received the British Empire Medal.

All but one of the 22 passengers were rescued through the broken windows onto the side of Car Z

National Library of New Zealand

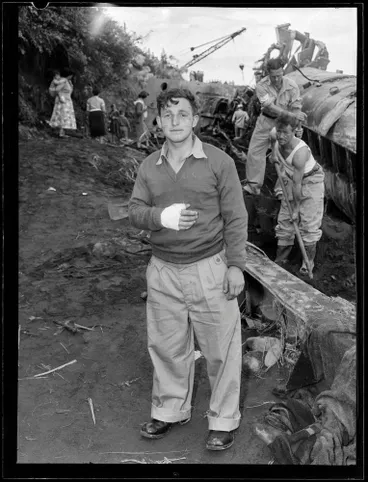

Passenger from Car Z shares his experience

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Train carriage on riverbank:

Arthur Bell and his wife had stopped on the other side of the flooded road bridge and seen the express train crash into the river. As his wife went to raise the alarm, Arthur helped rescue fifteen survivors from a carriage that had landed on the riverbank. Those who had managed to free themselves were swept further downstream before they were able to crawl ashore.

The Queen awarded Arthur Bell the British Empire Medal.

Scene at Tangiwai after railway disaster

Alexander Turnbull Library

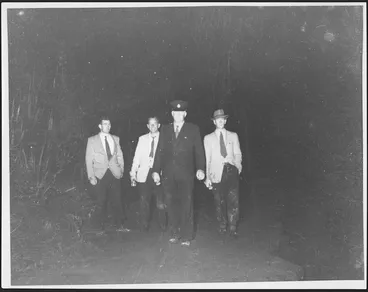

Waiōuru Police:

Leo Smidt, Waiōuru’s 22-year-old police constable, investigated reports by people of a roaring noise coming from the direction of forestry plantations. He was one of the first on the scene and directed the rescue until more senior staff arrived from Taihape.

Police officer and search volunteers

Alexander Turnbull Library

Sound clip: eyewitness report of Tangiwai disaster

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

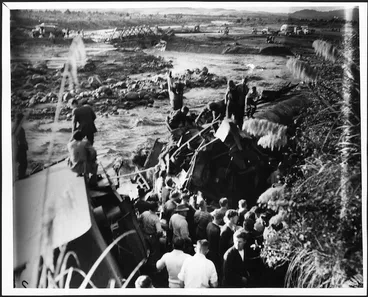

2B. Team Rescue Operation

A Disaster Co-ordination Centre was set up at the Ohakune Railway Station. Members of the public, train's crew, New Zealand Forest Service, Waiōuru Ministry of Works (MOW) camp, police, Navy personnel from HMS Irirangi , groups of farmers and other local volunteers worked throughout the night. Radio operators from Irirangi Naval Communications Station also gave assistance. The Waiōuru Military Camp provided help with transport and shelter for survivors and those involved in the rescue mission, and provided temporary mortuary facilities. Heavy moving equipment arrived to remove carriages and debris. In the meantime, rail traffic was diverted via New Plymouth and road traffic through the back roads.

Of the 285 persons on the express train, 134 were found to be safe. Many of the survivors were found "shocked, filthy, choked with silt and half blind with oil". (Source: 'Dealing with the dead', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/tangiwai-disaster/dealing-with-death, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 17-Jun-2014)

Rescue party officials at Tangiwai

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

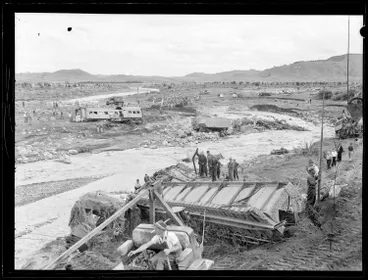

Men on the banks of the Whangaehu Stream at the scene of the railway disaster at Tangiwai

Alexander Turnbull Library

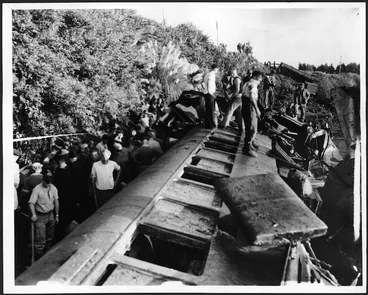

At the scene of the railway disaster at Tangiwai, with a group alongside wrecked railway carriages

Alexander Turnbull Library

Waiōuru Military Camp provided help with transport and shelter for survivors & rescuers, & temporary mortuary facilities

Alexander Turnbull Library

Location of the carriages marked on the photograph

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

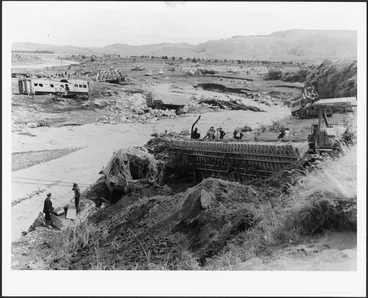

Showing train wreckage and the bridge in the distance

Auckland Libraries

Rescuers and passengers near the train wreckage

Auckland Libraries

Rescue workers carrying a stretcher

Alexander Turnbull Library

A woman sits, wrapped in a blanket, in the left foreground

Alexander Turnbull Library

Aerial view of the Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

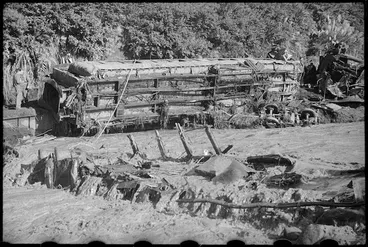

Wreckage at the scene of the railway disaster at Tangiwai

Alexander Turnbull Library

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Railway disaster at Tangiwai

Alexander Turnbull Library

Railway carriage on the bank of the Whangaehu Stream at the scene of the railway disaster at Tangiwai

Alexander Turnbull Library

Sound: Lionel Sceats remembers the Tangiwai disaster

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

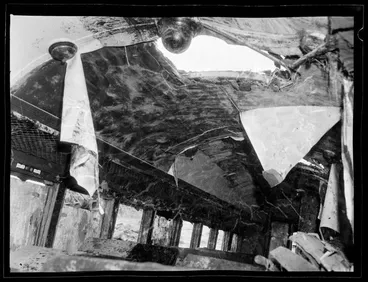

A wrecked railway carriage with passenger standing next to the seat he occupied at the time

Auckland Libraries

Men on the banks of the Whangaehu Stream at the scene of the railway disaster at Tangiwai

Alexander Turnbull Library

Railway carriage lying on its side at the scene of the railway disaster at Tangiwai

Alexander Turnbull Library

Group alongside a wrecked carriage at the scene of the railway disaster at Tangiwai

Alexander Turnbull Library

3. News broadcastS

Prime Minister on Christmas Day:

Prime Minister Sidney Holland announced with ‘profound regret’ news of the accident in a radio broadcast. He had spoken by phone from Waiōuru Military Camp to Wellington, where a recording was made on disc which was broadcast on Christmas Day.

Prime Minister Sidney Holland (centre)

The Manager of Railways, Mr H C Lusty (left?)

Auckland Libraries

Prime Minister Holland's Christmas Day announcement about the Tangiwai disaster

He had spoken by phone from Waiōuru Military Camp to Wellington, where a recording was made on disc which was broadcast

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Queen Elizabeth's Christmas broadcast with message of sympathy:

Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip were visiting New Zealand on their first royal tour when the disaster at Tangiwai happened. Queen Elizabeth made her Christmas broadcast from Auckland, finishing with a message of sympathy for the people of New Zealand.

Queen Elizabeth reads the Christmas message, 1953

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

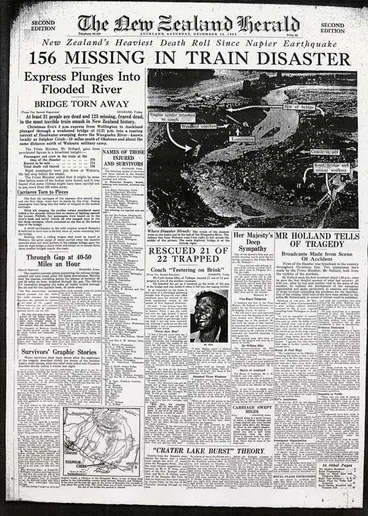

Newspaper articles first appeared on 26 Dec 1953:

As the following day after the tragedy was Christmas Day, there were no newspapers until 26 December. An information bureau was established at the Railway Social Hall in Wellington and was open 24 hours a day to answer queries about the accident.

Reporting the Tangiwai disaster

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

4. Survivors travel on the relief train to Auckland

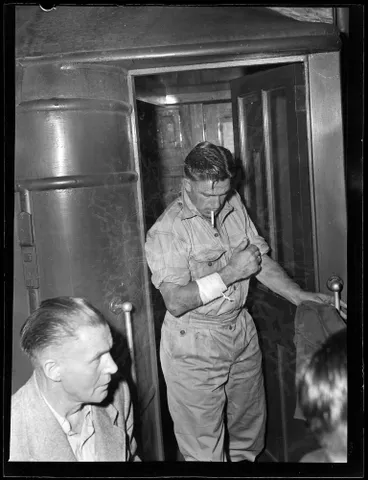

Tangiwai survivor Leslie Wasley on the relief train to Auckland after the Tangiwai Disaster

Survivor Leslie Wasley, Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

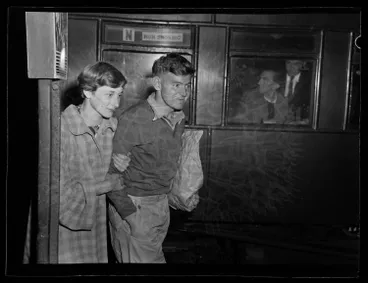

Survivors Sulenta and Wasley, Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster Relief Train, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Survivor Lewis Green, Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

5. SEARCHING FOR THE MISSING

In the following days, searches were carried out for those who were missing.

NUMBER OF CASUALTIES WAS 151:

The Board of Inquiry's Report (op cit, p. 4) stated: "Evidence obtained from police inquiries up to the date of this report established that the total number of persons on the train was 285. Of these, 134 are known to be safe and 131 bodies have been recovered... In addition, a further 20 persons are not accounted for. Thus the records show a total casualty list of 151 persons."

About 60 bodies were recovered by locals from the Mangamāhū section of the river. Bodies were also recovered as far away as the river mouth, 120 km downstream. Some of the 20 bodies that were never recovered may have been washed out to sea.

The engine driver Charles Parker and fireman Lancelot Redman were amongst those who lost their lives, which included 148 second-class passengers, and one first-class passenger.

Identifying the casualties:

A record of bodies and property recovered was made by George Twentyman, a constable, who was later in command of the rescue operation during the Wahine tragedy in 1968. The police laid out the bodies in coffins in a makeshift mortuary set up at the Waiōuru Military Camp. The police inspector in charge, Willis Brown, organised for relatives to assist with identification by viewing the partly opened coffins, with clergy present to give support. As some of those killed were recent arrivals to New Zealand they did not have relatives or local medical or dental records to help identify them. Those bodies that were unclaimed by relatives were transferred to hospital mortuaries in Wellington and Whanganui.

Coroner’s courts were convened at Waiōuru to determine identity and issue death certificates. Pathologist Dr J.O. Mercer pronounced the main causes of death to be drowning and asphyxiation by silt.

6. Tangi/Funerals

There were more than a hundred private funerals. On 31 December Prince Philip attended the state funeral for 21 unidentified victims who were buried in an 18 metre grave at Wellington’s Karori Cemetery. In April 1954 information from overseas confirmed that several of these bodies had been misidentified. An order was obtained to exhume the graves, a task that was carried out by police recruits. The bodies of 16, including eight whose remains were never identified, still lie at the Tangiwai National Memorial at Karori, which was dedicated in 1957.

A service was held in Westminster Abbey on Friday, 12 January 1954 at 12 noon. The order of service included a reading from Romans VIII, 18-28 and 31-end, read by the High Commissioner for New Zealand, Sir Frederick Doidge. An address by the Right Rev G V Gerard, former Lord Bishop of Waiapu, was part of the service. A copy of the service booklet is held by the National Library of New Zealand.

Tangiwai Memorial, Karori Cemetery, 31 December 1953

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

7. Board of inquiry held in 1954

On 18 January 1954, the Prime Minister Sidney Holland formed a Board of Inquiry to establish the cause of the disaster, determine whether it could have been prevented and to inquire into methods of preventing a similar occurrence. The Board of Inquiry sat from 26 January until 2 April. It's findings were reported on 23 April 1954 and published in Tangiwai Railway Disaster: Report of the Board of Inquiry (RE Owen, 30 April 1954).

Cause of the accident: erosion of volcanic ash & cracked ice

An inspection of Mt. Ruapehu's Crater Lake after the Tangiwai flood found that a second larger cave had been formed at a lower level near the existing cave:

"[W]here there had been outcrops of volcanic rock to the right or west of the cave there was another huge cave apparently formed by the collapse of that rock... [W]hile the lake was discharging through the first formed cave, water must have also been seeping through the volcanic ash and scoria alongside, to form another channel beneath the ice at lower level. Erosion in this channel may have reduced the strength of the ash barrier, and cracking movements in the ice above may have caused it to suddenly collapse." There was "no evidence that volcanic activity had played any part in causing the sudden collapse of the ash barrier, but this cannot be definitely ruled out. Mr G. Eiby, of the Seismological Observatory, reported that the seismograph at the Chateau did not record any earthquake or volcanic disturbance..." (Ibid, pp. 6-7)

The conclusion was that "the accident was caused by the sudden release from the Crater Lake on Mount Ruapehu through an outlet cave beneath the Whangaehu Glacier of a huge mass of water which was channelled down the Whangaehu River carrying with it a high content of ash from the 1945 eruption and blocks of ice due to the collapse of large volumes of the glacier. This flood, which can properly be termed a "lahar", proceeded down the mountain as a wave, uplifting huge quantities of sand, silt, and boulders. It was most violent and turbulent and of great destructive effect. It destroyed portion of the railway bridge at Tangiwai before the arrival of train No. 626, which was engulfed when proceeding across the bridge." (Ibid, p. 21)

Oct 1953: Swollen waters in the Crater Lake prior to the flood

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

After Dec 1953 lahar, the chasm in the foreground had been gouged out, washing away all the snow & exposing bare rock

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

By 29 December 1953 the Crater Lake's level had fallen by about 27 ft. and by 13 February 1954 the lake level had fallen another foot and the pile of fallen ice had grown until it nearly blocked the entrance to the second cave.

Crater Lake, 8 Jan 1954

National Library of New Zealand

IMPACT ON THE RAIL BRIDGE:

The findings stated that the Tangiwai Rail Bridge, which was built about 1906, was 198 ft. in length. It had eight piers and seven spans, of which four piers had been damaged and five spans dislodged. When the train crossed the bridge, the fourth pier had fallen, dislodged by the lahar of water, sand and boulders.

Piers:

"Pier No. 2 had the top portion broken off, and this was lying under the bridge between Piers 1 and 2. Pier No. 3 was smashed above the base into at least four pieces. Two pieces were found near the locomotive, one between Piers 2 and 3, but the remaining portion has not been found. Pier No.4 was removed bodily and broke into three pieces. The base portion, weighing about 126 tons, came to rest 70 yards downstream. The centre portion was found 300 yards downstream, but the top portion has not been located. Pier No. 5 was removed bodily and broke into at least two pieces. The top portion was found 50 yards downstream, but the lower portion has not been located. Piers 1, 6, 7, and 8 were not damaged." (Ibid, p. 16)

Spans:

"Span No. 1 (22 ft. plate girders): This span was dislodged and the south end was thrown upstream. Span No. 2 (44 ft. plate girders): This span was lying alongside the engine. Span No. 3 (44 ft. plate girders): This span was on the right bank of the river about 80 yards downstream, immediately downstream of and lying beside Car A. 1907. Spans No. 4 and 5 (both 22 ft. plate girders): One span was lying on the left bank near the bridge and the other has not been located. Spans 6 and 7 remained in place." (Ibid, p. 16)

The Tangiwai Bridge, which was 198 ft long, had 8 piers & 7 spans, of which 4 piers had been damaged & 5 spans dislodged

When the train crossed the bridge, the fourth pier had fallen, dislodged by the lahar of water, sand and boulders.

Alexander Turnbull Library

PREVIOUS DAMAGE TO THE BRIDGE:

The Report (Ibid, pp.12-13) found that the bridge's No. 4 pier had previously been damaged which may have weakened it:

23 January 1925: The Acting District Engineer had reported to the Chief Engineer: "Yesterday afternoon a] heavy swell came down the Whangaehu River, the river rising about 9 ft. and going down through the night to almost normal this morning. There was a fairly heavy scour on the upstream side of pier No. 4, this pier evidently having tilted over about half an inch. The track showed a bulge, towards the upstream side of about half an inch over this pier... The District Engineer was advised accordingly and instructed that should the scour undermine the foundation it should be underpinned by placing cement in sacks beneath the concrete and the hole then filled up with rock. The records do not disclose whether underpinning was carried out, but it was clear that the hole was filled with rock. From this it can be assumed that no underpinning was necessary."

9 March 1936: "Foreman of Works reported scour at Piers Nos. 3 and 4 and recommended 15 wagons of stone protection. This work was done and advised complete by Foreman of Works on 18 June 1936." 1 March 1944: "Foreman of Works reported to the District Engineer, having been called to the bridge to inspect Pier No. 3 on 28 February 1944. He reported that the river was in high flood and that a whirlpool had scoured a hole 10 ft. in diameter and 3 ft. deep on the upstream side of this pier. No damage was done to the foundations and the hole was filled in with stone."

25 June 1946: "District Engineer instructed the Foreman of Works regarding the placing of eight 5-ton concrete protective blocks in the vicinity of Pier No. 4. The Foreman Of Works reported on 3 July 1946 that the concrete blocks had been placed in position."

27 January 1948: "Foreman of Works reported: I think that if anything the creek bed is higher now than when the concrete blocks were placed in position and the blocks have not sunk at all. Between piers Nos. 4 and 5 there is practically no water and sand is banked well up round these piers except No. 4's river side where the main channel now flows. The concrete blocks here are well out of the water and scour can be rated as nil since last inspected."

From Jan 1948 until 24 December 1953, regular inspections reported there was no further damage.

THREE OTHER BRIDGES DESTROYED:

Besides the destruction of the railway and road bridges at Tangiwai, three further bridges were also destroyed: (i) a private bridge (Strachan's)near the Karioi State Forest Depot, (ii) the Ngamoki Bridge, and (iii) Whangaehu Valley Road Bridge.

Three other bridges were destroyed: A private bridge (Strachan's), Ngamoki Bridge, & Whangaehu Valley Bridge

Auckland Libraries

REPORT'S CONCLUSION:

James Healy, the superintending geologist at the Geological Survey, DSIR, concluded that no one was to blame for the disaster. The police found no evidence that legal blame could be attached to any party, and there were no prosecutions.

The Board recommended the installation of an early warning system upstream on the Whangaehu River to alert train control to high river flows.

Twisted train tracks at the scene of the railway disaster at Tangiwai

Alexander Turnbull Library

8. Rebuilding the Tangiwai Rail Bridge, 1954 - 1965

During the rescue operations, rail traffic was diverted via New Plymouth and road traffic through the back roads.

TEMPORARY BRIDGE USED, 1954-1965

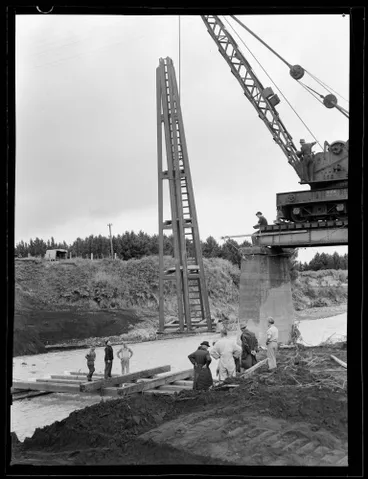

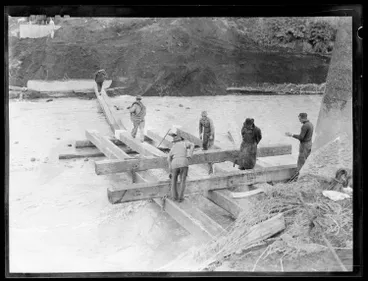

The Public Works Department and the Railways Department worked throughout the day and night to move debris from the Tangiwai Bridge and nearby banks, to build a temporary bridge.

Men working on cleared the site of the collapsed bridge

Auckland Libraries

Within a week the rail line was re-opened with temporary central pillars for the bridge in place until a new bridge was built. "There is a speed limit of about six miles an hour over the temporary bridge, which also has a 24-hour guard on it."

(Source: Papers Past, "Tangiwai rail bridge", Press, Vol.XC, Issue 27541, 24 December 1954, p. 13)

Makeshift bridge

Railway sleepers being carried across the makeshift bridge

Auckland Libraries

Bailey Bridge being prepared which was used from 1954-1965

There was a speed limit of about six miles an hour over the bridge which also had a 24 hour guard

Auckland Libraries

Tenders called for new bridge, 1955:

The Press reported (24 Dec 1954):

"Tenders lor a new Whangaehu railway bridge near Tangiwai will be called early in the New Year. The old bridge at Tangiwai was washed away by a flood on December 24, 1953, when a northbound Limited express fell into the river, with disastrous loss of life. A spokesman for the Railways Department said today that the present temporary bridge would be replaced by a bridge consisting of two 120-foot spans and one 40-foot span resting on deep concrete foundations. There is a speed limit of about six miles an hour over the temporary bridge, which also-has a 24-hour guard on it." (Ibid).

New bridge underway

A crane helping to erect pile-driving equipment for the construction of the new bridge

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Bridge Reconstruction, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Bridge Reconstruction, 1953

Auckland Libraries

Tangiwai Railway Disaster, 1953

Auckland Libraries

New bridge under construction, Tangiwai, Ruapehu district

Alexander Turnbull Library

New bridge officially opened, 19 Feb 1965:

The Press newspaper reported (22 Feb 1965):

"A new bridge over the Whangaehu river at Tangiwai was opened to traffic on Friday. It is the first permanent bridge to replace that destroyed in 1953 in the Tangiwai disaster. A three-span concrete bridge, it was three years in construction and replaces a Bailey bridge which has been in place for 12 years. It is 112 feet Situated 500 yards downstream from the previous bridge, it cuts a large corner off the highway."

Source: Papers Past: "Tangiwai Bridge", Press, Vol CIV, Issue 30881, 22 Feb 1965, p.1

New Tangiwai Bridge officially opened on Friday, 19 Feb 1965

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

9. EARLY WARNING SYSTEMs INSTALLED

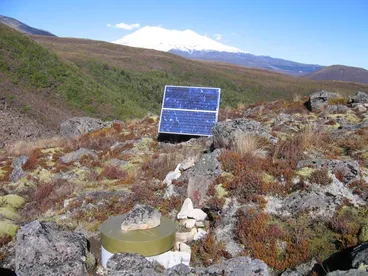

Earthquake monitoring equipment near crater Lake, April 1969:

In the 1960s, an A-frame hut was built on Dome peak or knoll near the Crater Lake. In April 1969, "a keen PhD student Ray Dibble (later a Professor at Victoria University) soon ran a cable to the hut and started to record volcanic earthquakes for his study... These first recordings were to come to a fiery and explosive end when at 12:33am on 22 June 1969 a violent eruption occurred through the Crater Lake. The eruption blast and ejected water from the lake blasted and washed the A-frame hut off its foundations, along with the earthquake monitoring equipment. The eruption produced lahars that significantly damaged other buildings on the Whakapapa Ski field, while ashfall also damaged buildings at Iwikau and Whakapapa villages. The site was re-established in March 1974 and was to suffer a similar fate in April 1975 when it was again destroyed by a large and violent volcanic eruption from the Crater Lake... Seismograph sites are usually known by a 3 or 4 letter code, the Dome site was given the code DRZ (Dome Ruapehu New Zealand)."

During 1975/76, a new site was established 700 metres north of the Crater Lake at the newly built Glacier Shelter Hut (GRZ). The equipment was placed in a vault under the shed which was later renamed the Dome Equipment Shed.

Source: GeoNet. 50 years of trusty service ends for the DOME (DRZ) seismograph site, 15 Feb 2018

In April 1969, monitoring system began in a shed near Crater Lake & was damaged by eruptions in June 1969 & April 1975

After April 1975 eruptions, equipment moved to new Dome Shelter (renamed Dome Equipment Shed) 700m north of Crater Lake

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

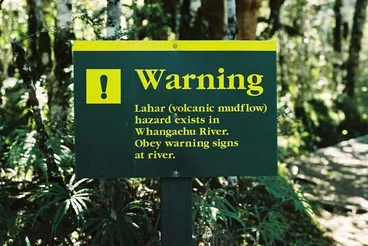

Lahar system, 1999:

Later in 1999, an early warning lahar system was installed in the Whangaehu River. The system measured the river level using radar and sent the level to the Network Control Centre at the Wellington Railway Station via an RF link to Waiōuru and then via the signalling network to Wellington. If the river changes level, an alarm is triggered which alerts staff. If the level indicates a significant risk, the control centre sets the signals on either side of the Tangiwai bridge to danger and warns trains in the area to stay clear by radio. The system has a failsafe feature which automatically sends a fault signal to the control centre. In this instance, trains in the area are restricted to 25 km/h (16 mph) and told to take extreme care over the Tangiwai bridge.

Lahar warning system installed 1999, to gauge flow depth & send a warning 15 min before a lahar reaches the bridge

Top photo: Normal flow of water against the tower. Bottom photo: flood conditions.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Photo taken on 24 Sept 1995 shows an eruption underway

Mud from an earlier eruption is covering the snow around the crater

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Lahar path: Heat of volcanic eruptions can melt snow & ice

Meltwater mixes with rocks & soil and sweeps down established channels, destroying vegetation along the way

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

After volcanic activity on Ruapehu, flood waters were piled up against the lahar warning gauge on 25 Sept 1995

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Lahar warning system extended, 2002:

Since 2002, the lahar warning system has also been backed up by the Eastern Ruapehu Lahar Alarm and Warning System (ERLAWS).

When a moderate-sized lahar flowed down the Whangaehu River on 18 March 2007, the monitoring and alarm system helped prevent injuries and minimise damage. The newer road bridges held up to the lahar and after inspection trains resumed operation over the railway bridge. See Youtube video of the lahar, including near the rail bridge. Source: Wikipedia: Eastern Ruapehu Lahar Alarm and Warning System

In 2002, the lahar system was upgraded with the Eastern Ruapehu lahar Alarm and Warning system

When a moderate-sized lahar occurred 18 March 2007, it helped to minimise damage & enabled inspection of railway bridge

Radio New Zealand

Volcanic warning system shifted, 2012:

In 2012, the volcanic eruption detection system had a $1 million upgrade by DoC, GNS Science, and snow fields operator Ruapehu Alpine Lifts. The detection system, which had been sited in a vault under the Dome Shelter Hut, was shifted further away from the Crater Lake to a new purpose-built Matarangi facility at Glacier Knob at the top of the mountain. The detection system, which runs on reticulated power, senses an eruption and within 30 seconds triggers a network of warning sirens. An eruption alert signal is also sent across DoC staff radios. In 2018, DoC reported the Dome Shelter shed near the Lake Crater was to be removed with the help of the NZ Army.

Source:

In 2012, eruption system was moved from Dome Shelter to purpose-built Matarangi facility at Glacier Knob

The system senses an eruption and within 30 secs triggers a network of warning sirens

Radio New Zealand

Sign erected by Dpt of Conservation on a track near Ohakune, to advise trampers of potential lahar hazard

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

National Geohazards Monitoring Centre opened in 2018:

Mt. Ruapheu is currently being monitored by the National Geohazards Monitoring Centre / Te Puna Mōrearea i te Rū (NGMC) which opened at GNS Science in December 2018. The Centre provides around-the-clock monitoring of natural geohazards – earthquakes, tsunami, volcanoes, landslides - by receiving live feeds from monitoring equipment provided via the GeoNet system, and data from international stations. Surveillance equipment includes remotely operated cameras powered by solar power which take an image every second and then transmit an image every 10 minutes to the data centres and website.

National Geohazards Monitoring Centre opened in Dec 2018

Radio New Zealand

10. Commemorative events & memorabilia

Dropping of wreath on Christmas eve:

A year after the disaster, the Wellington-to-Auckland express dropped a wreath into the Whangaehu River from the temporary railway bridge in memory of those who had died. This has since become an annual tradition whereby on Christmas Eve the express train slows as it crosses the new bridge across the Whangaehu River, and the driver throws a bunch of flowers into the water. A card reads: "In memory of all who died at Tangiwai on Christmas Eve, 1953." (Source: Christchurch City Libraries: Tangiwai rail disaster)

Unveiling of memorial at Karori Cemetery, 26 March 1957:

The Tangiwai National Memorial, designed by Government Architect Francis Gordon Wilson, was unveiled at the Karori Cemetery by Prime Minister Sidney Holland on 26 March 1957. It is inscribed with the names of the 151 people who lost their lives and stands by the graves of the 16 people unidentified at the time of the burial.

On 26 March 1957 the Tangiwai National Memorial was unveiled at the Karori Cemetery

Wellington City Libraries

Memorial dedicated by the Very Reverend James Baird, vice-president of the National Council of Churches

Alexander Turnbull Library

Erecting of memorials at Tangiwai, 1963 - 2017:

1963: White wooden cross. On the tenth anniversary of the disaster, a small white wooden cross was erected for the memorial ceremony at Tangiwai, which was attended by more than 300 people.

1989: Tangiwai Memorial obelisk. The granite obelisk was erected in place of the cross. The unveiling ceremony was attended by more than 200 people. The obelisk was designed by the New Zealand Master Monumental Masons Association Inc and erected by Anderson Memorials, Wanganui.

1994: Tangiwai Historic Reserve. The site of the disaster was declared a historic reserve - 17130 hectares of land adjacent to the Whangaehu River beside State Highway 49 between Ohakune and Waiōuru.

2003: Two new inscriptions on obelisk. On the 50th anniversary of the disaster, the obelisk was unveiled for a second time following the addition of two new inscriptions. The Governor-General, the Prime Minister and approximately 1000 people attended the ceremony. Thereafter, the official remembrance ceremony has been held at this site.

2017: Memorial to two railwaymen. More than 1000 people were gathered at the Tangiwai Historic Reserve on 7 May 2017 for the unveiling of a memorial to two railwaymen - engine driver Carles Parker and fireman Lancelot Redman - who lost their lives during the Tangiwai disaster.

In 1963, a small white cross was unveiled at Tangiwai, which was replaced with the Tangiwai Memorial obelisk in 1989

On the 50th Anniversary, the obelisk was unveiled for a second time following the addition of two new inscriptions.

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Tangiwai Historic Reserve declared in 1994, & a special memorial was unveiled to two railwaymen on 7 May 2017

Engine driver Charles Parker and fireman Lancelot Redman

Radio New Zealand

A scrapbook of clippings compiled by A.G. Bagnall, 1953-1979

Massey University

2009: Video created by the Auckland War Memorial Museum

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

2011 television film about the disaster was made by Lippy Pictures

NZ On Screen

2010: The Play 'The Second Test'

Remembers the day fast bowler Bob Blair played cricket after learning his bride-to-be had died in the Tangiwai tragedy

Radio New Zealand

2013: 60th Anniversary commemorations

Radio New Zealand

2018: About the Nicholls family who were one of two families that lost five members in the Tangiwai train disaster

Palmerston North City Library

2018: Description of the photograph processing for the reporting of the Tangiwai disaster

Palmerston North City Library

On 2 December 2023, to commemorate the 70th anniversary, the NZ Herald published the article “The scene from hell”: Tangiwai survivors reveal the true horror of NZ’s worst rail disaster which includes historic articles and links to six podcasts with the first entitled "Tangiwai: A Forgotten History".

70th anniversary commemorations held on 21 Jan 2024

Radio New Zealand

During the Commemorative ceremony one of the rescuers recounted his memories

Radio New Zealand

2024: Tangiwai Shield (cricket sporting trophy) to commemorate 1953 rail disaster unveiled on 3 Feb

(The new trophy was played for the first time when NZ & South Africa began cricket series in Tauranga on 4 Feb)

Radio New Zealand

Find out more:

Research paper: Contributions to the Geology of Mt. Ruapehu, New Zealand (1957)

Victoria University of Wellington

Book: Tangiwai disaster : and 30 other railway accidents in New Zealand (1972)

Howick Historical Village

Book: Tragedy on the track : Tangiwai and other New Zealand railway accidents (1986)

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

TV documentary (2002): Examines events and the Board of Inquiry finding

NZ On Screen

Te Ara: Historic volcanic activity - Ruapehu and the Tangiwai disaster (2006)

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

NZHistory: Tangiwai railway disaster (2020)

Article also includes references for further reading

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

This DigitalNZ story was updated in December 2024